Scopus, KCI, KoreaMed

Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition > Volume 10(2); 2019 > Article

- ORIGINAL ARTICLE Postoperative Weight Changes, Nutritional Status and Clinical Significance of Colorectal Cancer Patients

- Sun Young Kim, A.D, Ji Sun Kim, M.D, Eon Chul Han, M.D.

-

Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition 2019;10(2):46-53.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18858/smn.2019.10.2.46

Published online: December 30, 2019

Department of Surgery, Dongnam Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences, Busan, Korea

Department of Surgery, Dongnam Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences, Busan, Korea

- Correspondence to: Eon Chul Han, Department of Surgery, Dongnam Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences, 40 Jwadong-gil, Jangan-eup, Gijang-gun, Busan 46033, Korea Tel: +82-51-720-5034, Fax: +82-51-720-5914, E-mail: eonchulhan@gmail.com

The results of this study were presented by poster at the Korean Society of Coloproctology 2018, Kwangju, Republic of Korea held from 30th march to 1st April 2018.

Copyright: © The Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 2,318 Views

- 14 Download

- 2 Crossref

Abstract

-

Purpose: Although weight loss is an important factor for assessing the nutritional status, patient counselling or management is limited due to fewer studies on weight loss after colorectal cancer surgery.

-

Materials and Methods: Totally, 374 patients were included in the analysis (between August 2010 to December 2016). Patients’ weight was determined before surgery, and at 1 week, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after surgery. Change in weight was reviewed based on the gender and administration of chemotherapy. Severe weight loss is defined as greater than 5% weight loss after surgery.

-

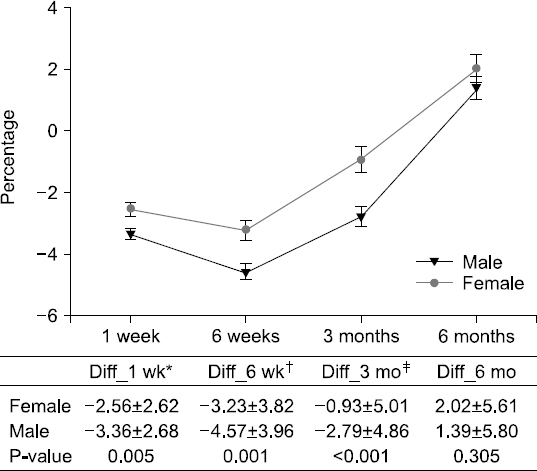

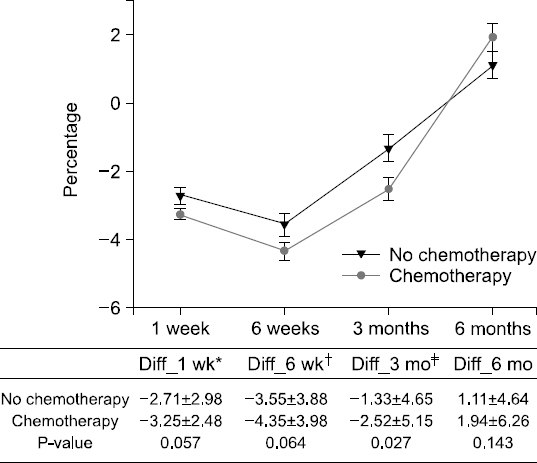

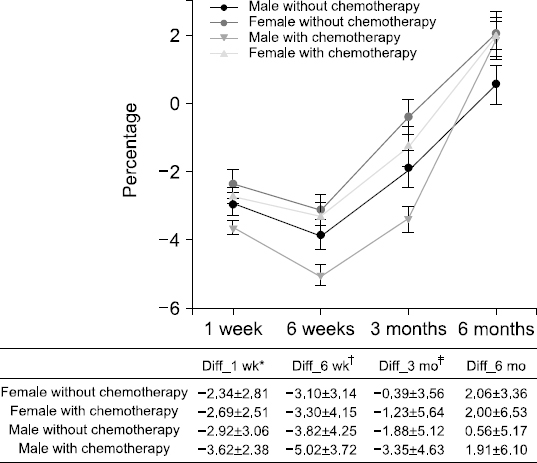

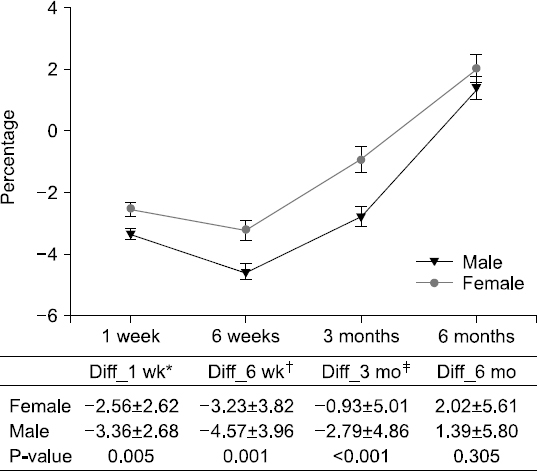

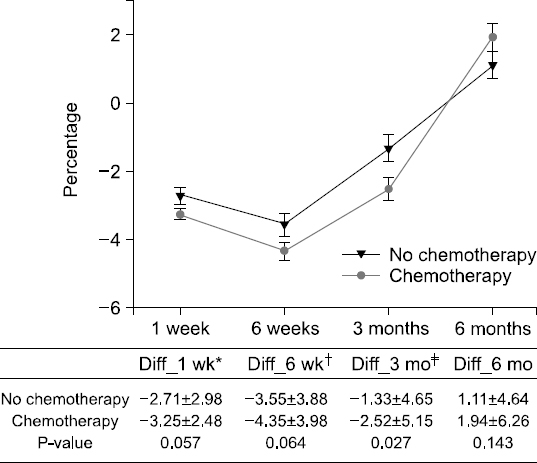

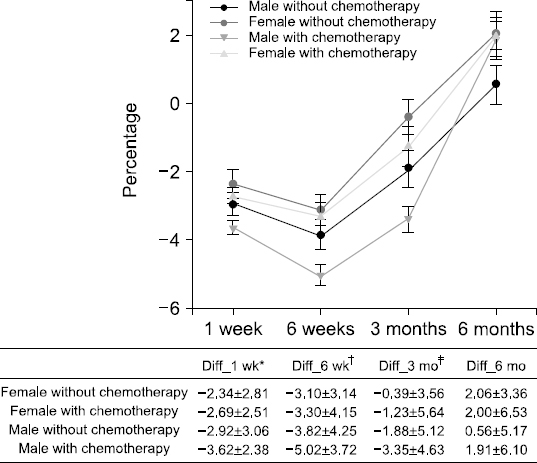

Results: The weight changes post-surgery at 1 week (−2.56±2.62 vs. −3.36±2.68, P<0.005), 6 weeks (−3.23±3.82 vs. −4.57±3.96, P=0.001), and 3 months (−0.93±5.01 vs. −2.79±4.86, P<0.001) were significantly greater in male subjects, as compared to female patients. However, at 6 months post-surgery, most patients showed weight gain with no statistical significance between the genders (1.11±4.64 vs. 1.94±6.26, P=0.143). Weight change based on treatment (with or without chemotherapy) reveal significant differences between the genders at 3 months post-surgery only (−1.33±4.65 vs. −2.52 ±5.15, P=0.027). Multivariate analysis for factors of severe weight loss show that the male gender [adjusted odds ratio (OR): 1.83, P=0.027)], adjuvant chemotherapy (adjusted OR 2.11, P=0.008), and presence of post-operative complications (adjusted OR 2.12, P=0.029) were significant factors.

-

Conclusion: In postoperative colorectal cancer patients, the weight and nutritional status require careful monitoring for at least 2 months after surgery, in order to prevent hindrance to chemotherapy. (Surg Metab Nutr 2019;10:-53)

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

- 1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:74-108. ArticlePubMed

- 2. Baek Y, Yi M. Factors influencing quality of life during chemotherapy for colorectal cancer patients in South Korea. J Korean Acad Nurs 2015;45:604-12. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 3. Wie GA, Cho YA, Kim SY, Kim SM, Bae JM, Joung H. Prevalence and risk factors of malnutrition among cancer patients according to tumor location and stage in the National Cancer Center in Korea. Nutrition 2010;26:263-8. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Bae JM, Kim S, Kim YW, Ryu KW, Lee JH, Noh JH, et al. Health-related quality of life among disease-free stomach cancer survivors in Korea. Qual Life Res 2006;15:1587-96. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Yu W, Seo BY, Chung HY. Postoperative body-weight loss and survival after curative resection for gastric cancer. Br J Surg 2002;89:467-70. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 6. Arends J, Baracos V, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Calder PC, Deutz NEP, et al. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr 2017;36:1187-96. ArticlePubMed

- 7. Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT, Band PR, Bennett JM, Bertino JR, et al. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Med 1980;69:491-7. Article

- 8. Martin L, Senesse P, Gioulbasanis I, Antoun S, Bozzetti F, Deans C, et al. Diagnostic criteria for the classification of cancer-associated weight loss. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:90-9. ArticlePubMed

- 9. Ravasco P, Monteiro-Grillo I, Vidal PM, Camilo ME. Nutritional deterioration in cancer:the role of disease and diet. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2003;15:443-50. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Cunningham D, Atkin W, Lenz HJ, Lynch HT, Minsky B, Nordlinger B, et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2010;375:1030-47. ArticlePubMed

- 11. Aaldriks AA, van der Geest LG, Giltay EJ, le Cessie S, Portielje JE, Tanis BC, et al. Frailty and malnutrition predictive of mortality risk in older patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Geriatr Oncol 2013;4:218-26. ArticlePubMed

- 12. Schwegler I, von Holzen A, Gutzwiller JP, Schlumpf R, Mühlebach S, Stanga Z. Nutritional risk is a clinical predictor of postoperative mortality and morbidity in surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2010;97:92-7. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 13. Eskicioglu C, Forbes SS, Aarts MA, Okrainec A, McLeod RS. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs for patients having colorectal surgery:a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:2321-9. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 14. Zhuang CL, Ye XZ, Zhang XD, Chen BC, Yu Z. Enhanced recovery after surgery programs versus traditional care for colorectal surgery:a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:667-78. ArticlePubMed

- 15. Maurício SF, Xiao J, Prado CM, Gonzalez MC, Correia MITD. Different nutritional assessment tools as predictors of postoperative complications in patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection. Clin Nutr 2018;37:1505-11. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Huang DD, Wang SL, Zhuang CL, Zheng BS, Lu JX, Chen FF, et al. Sarcopenia, as defined by low muscle mass, strength and physical performance, predicts complications after surgery for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2015;17:O256-64. ArticlePubMed

- 17. Reisinger KW, van Vugt JL, Tegels JJ, Snijders C, Hulsewé KW, Hoofwijk AG, et al. Functional compromise reflected by sarcopenia, frailty, and nutritional depletion predicts adverse postoperative outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg 2015;261:345-52. ArticlePubMed

- 18. Musallam KM, Tamim HM, Richards T, Spahn DR, Rosendaal FR, Habbal A, et al. Preoperative anaemia and postoperative outcomes in non-cardiac surgery:a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2011;378:1396-407. ArticlePubMed

- 19. Leichtle SW, Mouawad NJ, Lampman R, Singal B, Cleary RK. Does preoperative anemia adversely affect colon and rectal surgery outcomes? J Am Coll Surg 2011;212:187-94. ArticlePubMed

- 20. Han EC, Ryoo SB, Park BK, Park JW, Lee SY, Oh HK, et al. Surgical outcomes and prognostic factors of emergency surgery for colonic perforation:would fecal contamination increase morbidity and mortality? Int J Colorectal Dis 2015;30:1495-504. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 21. Inagaki J, Rodriguez V, Bodey GP. Proceedings:causes of death in cancer patients. Cancer 1974;33:568-73. ArticlePubMed

- 22. Espat NJ, Moldawer LL, Copeland EM 3rd. Cytokine-mediated alterations in host metabolism prevent nutritional repletion in cachectic cancer patients. J Surg Oncol 1995;58:77-82. ArticlePubMed

- 23. De Blaauw I, Deutz NE, Von Meyenfeldt MF. Metabolic changes of cancer cachexia--second of two parts. Clin Nutr 1997;16:223-8. ArticlePubMed

- 24. Kern KA, Norton JA. Cancer cachexia. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1988;12:286-98. ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- The impact of pre‐surgery nutrition intervention on weight loss, nutrition status, and quality of life in colorectal cancer patients with elective surgery

Wen Lynn Teong, Wei Yee Wong, Su Lin Lim, Choon Hui Low, Cassandra Lim Duan Qi, Ruochen Du

Malignancy Spectrum.2025; 2(2): 74. CrossRef - Serial measurements of body composition using bioelectrical impedance and clinical usefulness of phase angle in colorectal cancer

Seung‐Rim Han, Jung Hoon Bae, Chul Seung Lee, Abdullah Al‐Sawat, Soo Ji Park, Hyo Jin Lee, Mi Ran Yoon, Hyeong Yong Jin, Yoon Suk Lee, Do Sang Lee, In Kyu Lee

Nutrition in Clinical Practice.2022; 37(1): 153. CrossRef

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Demographic data and clinical characteristics according to whether they were treated with chemotherapy

| Total number of patients or average (N=374) | Patients without chemotherapy (N=137) | Patients with chemotherapy (N=237) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.599 | |||

| Male | 231 (61.8%) | 87 (63.5%) | 144 (60.8%) | |

| Female | 143 (38.2%) | 50 (36.5%) | 93 (39.2%) | |

| Age (mean±SD, years) | 63.8±11.2 | 65.6±11.6 | 62.8±10.8 | 0.021 |

| Body mass index (mean±SD, kg/m2) | 23.4±3.3 | 23.7±3.2 | 23.2±3.4 | 0.253 |

| ASA | 0.116 | |||

| 1 | 180 (48.1%) | 59 (43.1%) | 121 (51.0%) | |

| 2 | 183 (48.8%) | 71 (51.8%) | 112 (47.3%) | |

| 3 | 11 (2.9%) | 7 (5.1%) | 4 (1.7%) | |

| Instant nutrition assessment | 0.932 | |||

| Good | 244 (65.2%) | 89 (65.0%) | 155 (65.4%) | |

| Poor | 130 (34.8%) | 48 (35.0%) | 82 (34.6%) | |

| Location of colorectal cancer | 0.195 | |||

| Right | 130 (34.8%) | 45 (32.8%) | 85 (35.9%) | |

| Left | 177 (47.3%) | 61 (44.5%) | 116 (48.9%) | |

| Rectum | 67 (17.9%) | 31 (22.7%) | 36 (15.2%) | |

| Method of operation | 0.001 | |||

| Open | 104 (27.8%) | 24 (17.5%) | 80 (33.8%) | |

| Laparoscopy | 270 (72.2%) | 113 (82.5%) | 157 (66.2%) | |

| TNM stage | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 13 (3.5%) | 13 (9.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 1 | 77 (20.6%) | 77 (56.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 2 | 98 (26.2%) | 34 (24.8%) | 64 (27.0%) | |

| 3 | 135 (36.1%) | 11 (8.0%) | 124 (52.3%) | |

| 4 | 51 (13.6%) | 2 (1.5%) | 49 (20.7%) | |

| Complication | 0.303 | |||

| No | 328 (87.7%) | 117 (85.4%) | 211 (89.0%) | |

| Yes | 46 (12.3%) | 20 (14.6%) | 26 (11.0%) | |

| Length of stay (mean±SD, days) | 10.1±3.9 | 9.6±3.6 | 10.3±4.2 | 0.086 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 13.2±46.6 | 3.7±4.2 | 18.7±57.6 | <0.001 |

| ≤5 | 253 (67.6%) | 111 (81.0%) | 142 (59.9%) | <0.001 |

| >5 | 121 (32.4%) | 26 (19.0%) | 95 (40.1%) | |

| Severe weight loss | ||||

| Postoperative 1 week | 76 (20.3%) | 21 (15.3%) | 55 (23.2%) | 0.068 |

| Postoperative 6 weeks | 138 (36.9%) | 42 (30.7%) | 96 (40.5%) | 0.057 |

| Postoperative 3 months | 87 (23.3%) | 23 (16.8%) | 64 (27.0%) | 0.024 |

| Postoperative 6 months | 32 (8.6%) | 8 (5.8%) | 24 (10.1%) | 0.153 |

Nutritional assessment compared with preoperative and postoperative according to whether they were treated with chemotherapy

| Preoperative status | Postoperative after 6 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients without chemotherapy (N=137) | Patients with chemotherapy (N=237) | P-value | Patients without chemotherapy (N=137) | Patients with chemotherapy (N=237) | P-value | |

| Lymphocyte | 1847±639 | 1790±608 | 0.387 | 1950±662 | 1759±658 | 0.007 |

| <1500/μL | 118 (86.1%) | 203 (85.7%) | 0.899 | 34 (68.0%) | 38 (76.0%) | 0.387 |

| ≥1500/μL | 19 (13.9%) | 34 (14.3%) | 16 (32.0%) | 12 (24.0%) | ||

| Albumin | 4.1±0.4 | 4.0±0.5 | 0.022 | 4.2±0.4 | 4.1±0.4 | 0.007 |

| <3.5 g/dL | 128 (93.4%) | 216 (91.1%) | 0.432 | 135 (98.5%) | 235 (99.2%) | 0.577 |

| ≥3.5 g/dL | 9 (6.6%) | 21 (8.9%) | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (0.8%) | ||

| Hemoglobin | 12.9±2.0 | 12.3±2.1 | 0.009 | 13.1±1.6 | 12.7±1.7 | 0.043 |

| Anemia | 0.009 | 0.009 | ||||

| No | 84 (61.3%) | 112 (47.3%) | 95 (69.3%) | 132 (55.7%) | ||

| Yes | 28 (38.7%) | 125 (52.7%) | 42 (30.7%) | 105 (44.3%) | ||

| Instant nutrition assessment | 0.932 | 0.021 | ||||

| Good | 88 (65.0%) | 155 (65.4%) | 101 (73.7%) | 147 (62.0%) | ||

| Poor | 49 (35.0%) | 82 (34.6%) | 36 (26.3%) | 90 (38.0%) | ||

| 1 | 88 (64.2%) | 155 (65.4%) | 0.276 | 101 (73.7%) | 147 (62.0%) | 0.048 |

| 2 | 40 (29.2%) | 61 (25.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.8%) | ||

| 3 | 4 (2.9%) | 3 (1.3%) | 34 (24.8%) | 87 (36.7%) | ||

| 4 | 5 (3.7%) | 18 (7.6%) | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (0.4%) | ||

Nutritional assessment compared with preoperative and postoperative according to patients’ sex and whether they were treated with chemotherapy

| Male patients without chemotherapy (N=87) | Female patients without chemotherapy (N=50) | Male patients with chemotherapy (N=144) | Female patients with chemotherapy (N=93) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 6 months after surgery | Preoperative | 6 months after surgery | Preoperative | 6 months after surgery | Preoperative | 6 months after surgery | |

| Lymphocyte | 1868±670 | 1935±676 | 1811±587 | 1977±643 | 1828±633 | 1814±678 | 1731±565 | 1674±619 |

| <1500/μL | 59 (67.8%) | 63 (72.4%) | 34 (68.0%) | 38 (76.0%) | 98 (68.1%) | 96 (66.7%) | 60 (64.5%) | 52 (55.9%) |

| ≥1500/μL | 28 (32.2%) | 24 (27.6%) | 16 (32.0%) | 12 (24.0%) | 46 (31.9%) | 48 (33.3%) | 33 (35.5%) | 41 (44.1%) |

| Albumin | 4.2±0.4 | 4.2±0.3 | 4.1±0.5 | 4.2±0.3 | 4.1±0.4 | 4.1±0.3 | 3.9±0.5 | 4.1±0.3 |

| <3.5 g/dL | 85 (94.3%) | 85 (97.7%) | 46 (92.0%) | 50 (100%) | 135 (93.8%) | 142 (98.6%) | 81 (87.1%) | 93 (100%) |

| ≥3.5 g/dL | 5 (5.7%) | 2 (2.3%) | 4 (8.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (6.3%) | 2 (1.4%) | 12 (12.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Hemoglobin | 13.6±2.0 | 13.6±1.5 | 11.8±1.6 | 12.2±1.2 | 13.1±2.1 | 13.3±1.7 | 11.2±1.5 | 11.9±1.2 |

| Anemia | ||||||||

| No | 59 (67.8%) | 62 (71.3%) | 25 (50.0%) | 33 (66.0%) | 84 (58.3%) | 88 (61.1%) | 28 (30.1%) | 44 (47.3%) |

| Yes | 28 (32.2%) | 25 (28.7%) | 25 (50.0%) | 17 (34.0%) | 60 (41.7%) | 56 (38.9%) | 65 (69.9%) | 49 (52.7%) |

| Instant nutrition assessment grade | ||||||||

| 1 | 57 (65.5%) | 63 (72.4%) | 31 (62.0%) | 38 (76.0%) | 97 (67.4%) | 95 (66.0%) | 58 (62.3%) | 52 (55.9%) |

| 2 | 25 (28.7%) | 22 (25.3%) | 15 (30.0%) | 12 (24.0%) | 38 (26.4%) | 2 (1.4%) | 23 (24.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 3 | 2 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 46 (31.9%) | 2 (2.2%) | 41 (44.1%) |

| 4 | 3 (3.4%) | 2 (2.3%) | 3 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (5.6%) | 1 (0.7%) | 10 (10.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Factors for severe weight loss at 3 months post-surgery after univariate and multivariate analyses.

| Patients with weight loss over -5% of postoperative after 3months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| Patients with weight loss over -5% n (%) | P | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P | |

| Sex | 0.016 | 0.027 | ||

| Female | 24/143 (16.8) | 1 | ||

| Male | 64/231 (27.7) | 1.83 (1.07~3.13) | ||

| Age | 0.677 | |||

| <65 years | 45/148 (24.5) | |||

| ≥65 years | 43/147 (22.6) | |||

| ASA | 0.151 | |||

| I | 36/178 (20.2) | |||

| II and III | 52/144 (26.5) | |||

| Body mass index | 0.295 | |||

| <25 | 56/255 (22.0) | |||

| ≥25 | 32/119 (26.9) | |||

| Comorbidity | 0.292 | |||

| No | 35/167 (21.0) | |||

| Yes | 53/207 (25.6) | |||

| Location of colorectal cancer | 0.096 | 0.100 | ||

| Right and Left | 67/307 (21.8) | 1 | ||

| Rectum | 21/67 (31.3) | 1.66 (0.91~3.05) | ||

| Instant nutrition assessment | 0.508 | |||

| Good | 60/244 (24.6) | |||

| Poor | 28/130 (21.5) | |||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.510 | |||

| ≤5 | 57/253 (22.5) | |||

| >5 | 31/121 (25.6) | |||

| Method of operation | 0.677 | |||

| Open | 26/104 (25.0) | |||

| Laparoscopy | 62/270 (23.0) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 0.019 | 0.008 | ||

| No | 23/137 (16.8) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 65/237 (27.4) | 2.11 (1.22~3.65) | ||

| Complication | 0.022 | 0.029 | ||

| No | 71/328 (21.6) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 17/46 (37.0) | 2.12 (1.08~4.17) | ||

| Cancer stage | 0.202 | |||

| Non-advanced | 39/188 (20.7) | |||

| Advanced | 49/186 (26.3) | |||

| Anemia | 0.135 | |||

| No | 40/196 (20.4) | |||

| Yes | 48/178 (27.0) | |||

| Albumin | 0.979 | |||

| <3.5 g/dL | 81/344 (23.5) | |||

| ≥3.5 g/dL | 7/30 (23.3) | |||

| Lymphocyte | 0.593 | |||

| <1500/μL | 74/321 (23.1) | |||

| ≥1500/μL | 14/53 (23.5) | |||

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN Cite

Cite