Abstract

-

Purpose

It aims to investigate the contents of food supplies, gastrointestinal symptoms, and stated preferences of evacuees during the first two weeks after the earthquake.

-

Methods

Thirty-four evacuees from evacuation shelters and 12 evacuees from geriatric care facilities were surveyed. Subjective and comprehensive nutritional assessment questionnaires were administered to the evacuees, and their dissatisfaction and preferences were also recorded in an open-ended format.

-

Results

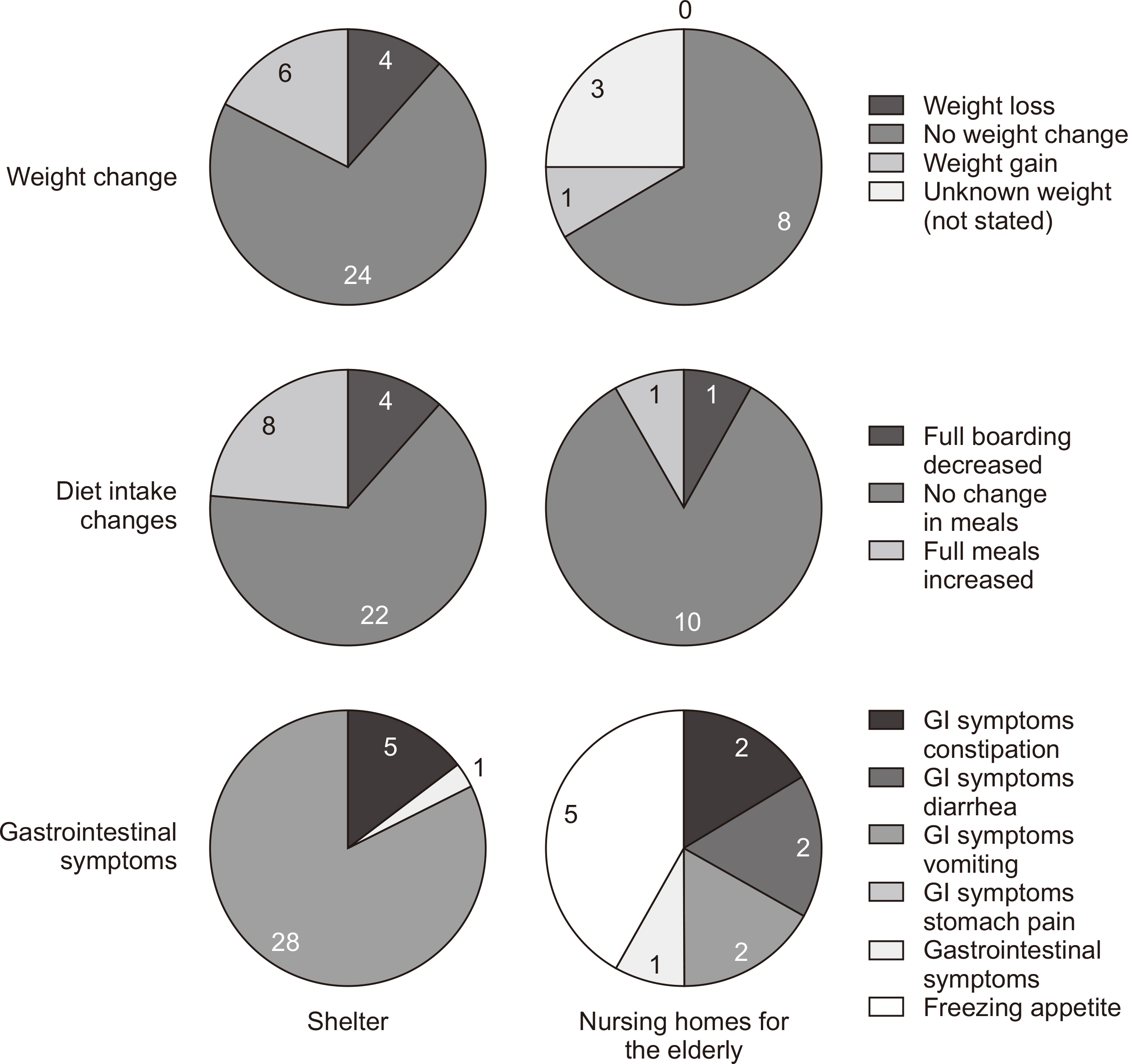

Weight decreased, remained unchanged, increased, or was unknown for 4, 24, 6, and 0 evacuees from the shelters and in 0, 8, 1, and 3 evacuees from the facilities. The number of respondents who reported a decrease, change, or decrease in food intake was 4, 22, and 1 from the evacuation centers and 1, 10, and 1 from the facilities, indicating a large number of changes in the evacuation centers. Reasons for weight gain included “feeling that they should not leave food behind,” “eating a lot of high-calorie food,” and “eating sweets and cup noodles.” Constipation was the most common gastrointestinal symptom (n=5) in the evacuation centers, while diverse symptoms were reported from the facilities. Constipation in the facilities was thought to be related to the high carbohydrate content of the food. Only two respondents were satisfied with the shelter, and the majority complained of dissatisfaction. The most common complaints were “I don’t like bread in the morning (I prefer rice);” “Too sweet;” and “Onigiri (rice ball) is too big,” but there were also complaints about the eating environment on the floor, such as “I lose [my] appetite when eating on the floor due to abdominal pressure” (I prefer to eat on a chair at a table). The majority of the respondents in the facilities did not have any complaints. All of the respondents in the shelters expressed a wide variety of food preferences, including vegetables, rice in the morning, meat, fruit, and foods that were not available due to lack of refrigeration, such as carbonated beverages and ice cream. Some respondents expressed that they were tired of being given food unilaterally and having no choice, such as “I want to choose my own food” and “I want a vending machine [to choose my own food].” There were almost no requests for food at the facilities, and the majority of the respondents were satisfied with their situation. The food was supplied by volunteers and the Self-Defense Forces, which were out of sync with the needs of the evacuees at the evacuation center. However, at the facilities, food was sent to a geriatric care facility in a remote area that accounted for the needs of the victims.

-

Conclusion

Evacuees were grateful for the food supplies immediately after the disaster, but gradually became dissatisfied. Meals are one of the pleasures in evacuation centers and are important for reducing mental stress. Evacuation centers should consider the needs of evacuees when providing food to evacuees.

-

Keywords: Diet; Digestive symptoms; Disaster; Earthquakes; Shelter

Introduction

Evacuees in evacuation centers in disaster-stricken areas are grateful and highly satisfied with food supplies after a disaster strikes, but dissatisfaction and requests for food rationing appear after about two weeks (the author’s experience in the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake/evacuation center survey in the Great East Japan Earthquake). The authors also surveyed food problems in evacuation centers about one month after the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011, and reported that food rations were biased toward carbohydrates [

1].

An earthquake with a 7.0 intensity struck on April 14, 2016, at about 21:26 at night.

A series of earthquakes, including two in rapid succession, occurred in Kumamoto and Oita prefectures and were collectively named the Kumamoto earthquakes. The number of fatalities, including related deaths, reached 273, and more than 2,700 people were injured. Up to 47,000 people were forced to live temporarily in evacuation centers due to damage to their houses. Hyogo Medical University, where the author was working at the time, dispatched Disaster Medical Assistant Team and a rescue team after the disaster. The author worked as a relief worker from April 27–30 of the same year. The rescue team was assigned to the Kumamoto Prefecture Disaster Relief Team.

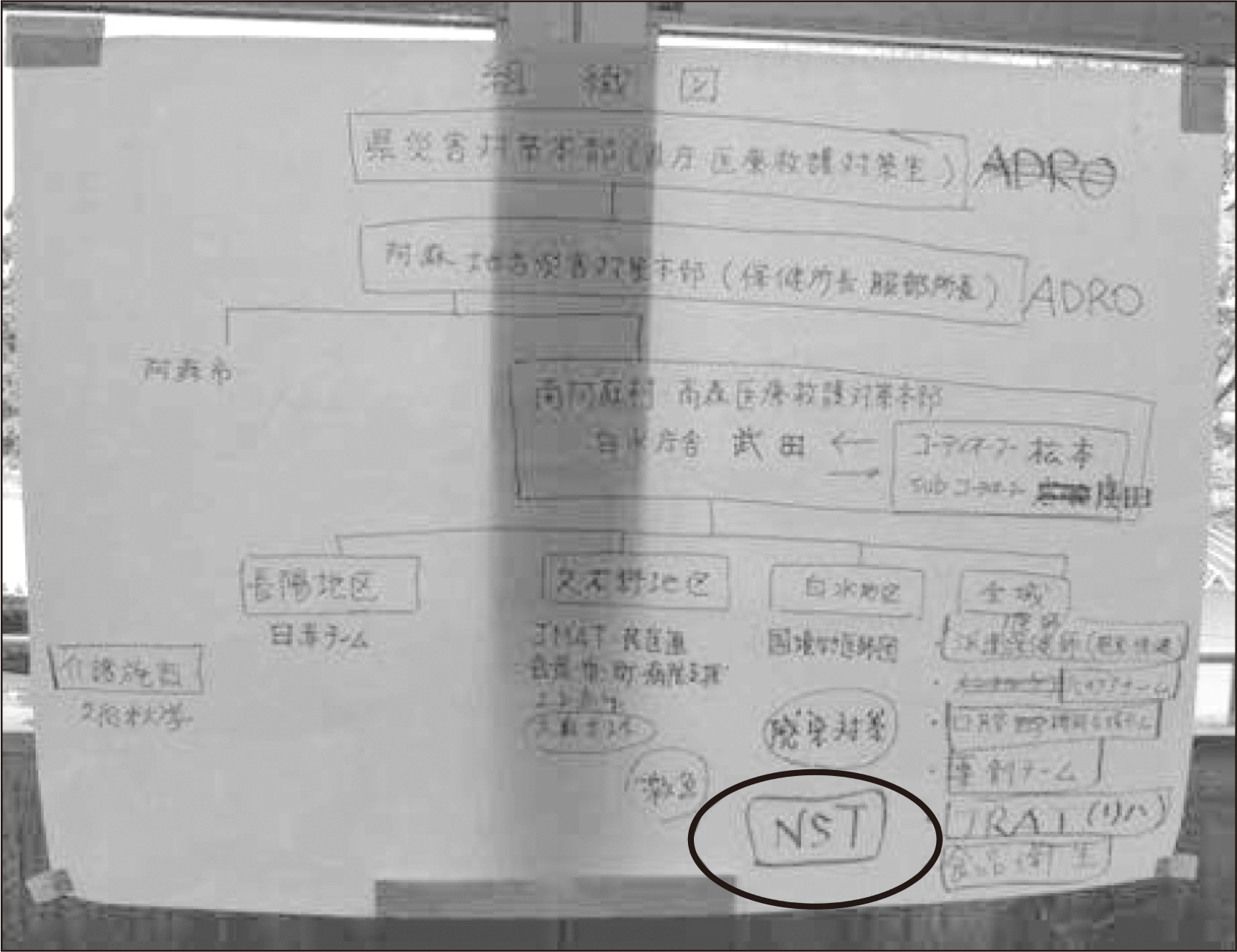

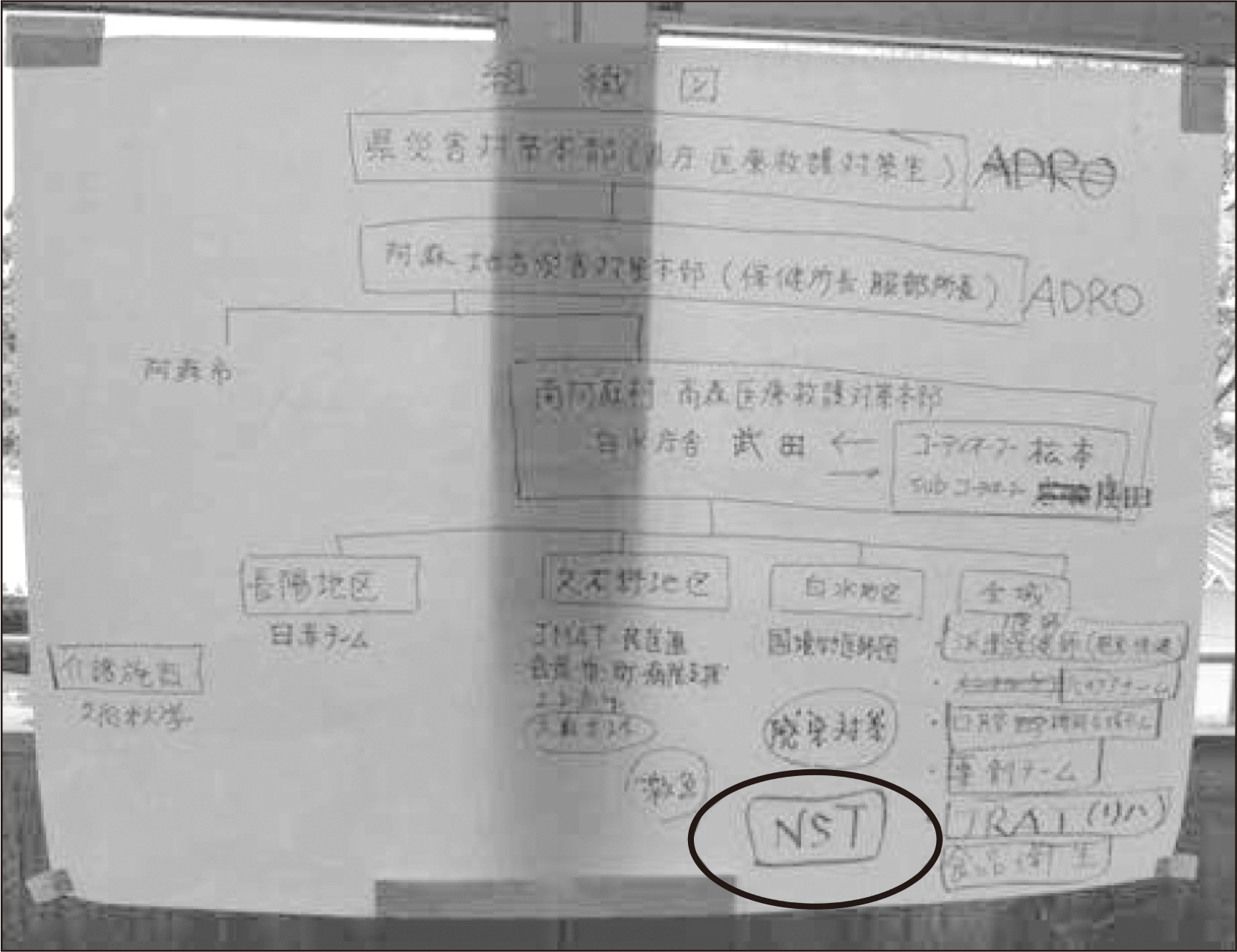

An Nutrition Support Team (NST) was established, which was led by the author of the Minamiaso Takamori Medical Rescue Task Force under the Emergency Response Headquarters (Prefectural Government Medical Rescue Task Force Office) (

Fig. 1), and the author was appointed as a member of the NST.

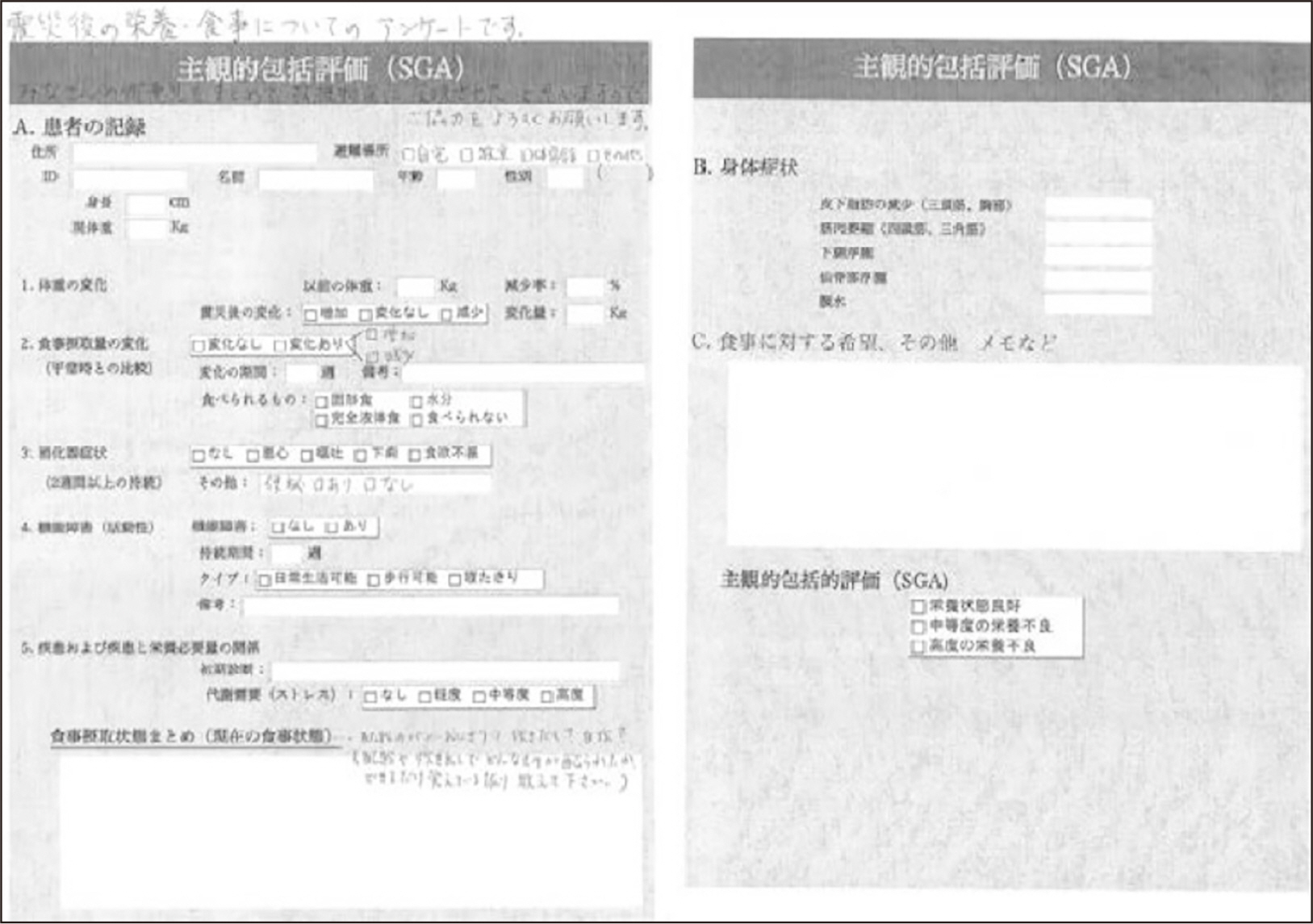

A cross-district NST was locally assembled and activities were initiated. First, a survey was conducted at evacuation centers and geriatric care facilities using the Subjective General Assessment (SGA), which revealed problems at evacuation centers.

This paper introduces the results of the survey and outlines the problems and solutions for food in evacuation shelters, with some personal observations, in comparison with survey results from the geriatric care facilities.

Objective

It aims to investigate the dissatisfaction and preferences of evacuees, approximately two weeks after the Kumamoto earthquake, in evacuation shelters and geriatric care facilities according to their different backgrounds and to identify areas for improvement.

Methods

Target facilities (n=34 people):

Evacuation centers: Minamiaso Junior High School (Choyo area), Hakusui Town Hall (Hakusui area)

Care facilities (n=12 people):

Group home Tsubame, Yono-oka-so (special nursing home for the elderly), and others, Sun and Moon Residential Care Home for the Elderly, Hanamizuki Private Care Home for the Elderly, unnamed nursing home (no record of names, n=11 people),, home (1 person)

Team organization:

Team 1 (NST): One doctor (author) and three public health nurses were appointed as members, in charge of two evacuation centers (Minamiaso Junior High School and Hakusui Town Hall) and one nursing home (Group Home Tsubame).

Team 2: Kurume University Rescue Team; 3 medical care facilities

The three nursing homes were: Yono-Oka-so (special nursing home), Sun and Moon Residential Care Home for the Elderly, and Hanamizuki Private Nursing Home for the Elderly.

Team 3: Fukuoka Dental College Rescue Team. The team was in charge of visiting nursing homes and homes with unknown names (no records).

Surveyed people:

Evacuation shelters: 8 males, 26 females (n=34), average age 59.3 years old

Sanatoriums, etc.: 0 males, 12 females, 86.4 years old, 1 at home.

Only one was at home.

Although the researcher subjectively selected the survey targets so as not to bias the age and gender of the survey targets, there were many women in the shelters during the daytime, and many of those who responded to the survey were women, so the survey was biased toward women. In the sanatoriums, the number of survey targets was considerably smaller than in the evacuation centers because the survey was limited to residents who were able to answer the SGA. For unknown reasons, all of those who responded to the survey were women.

Interview survey methods:

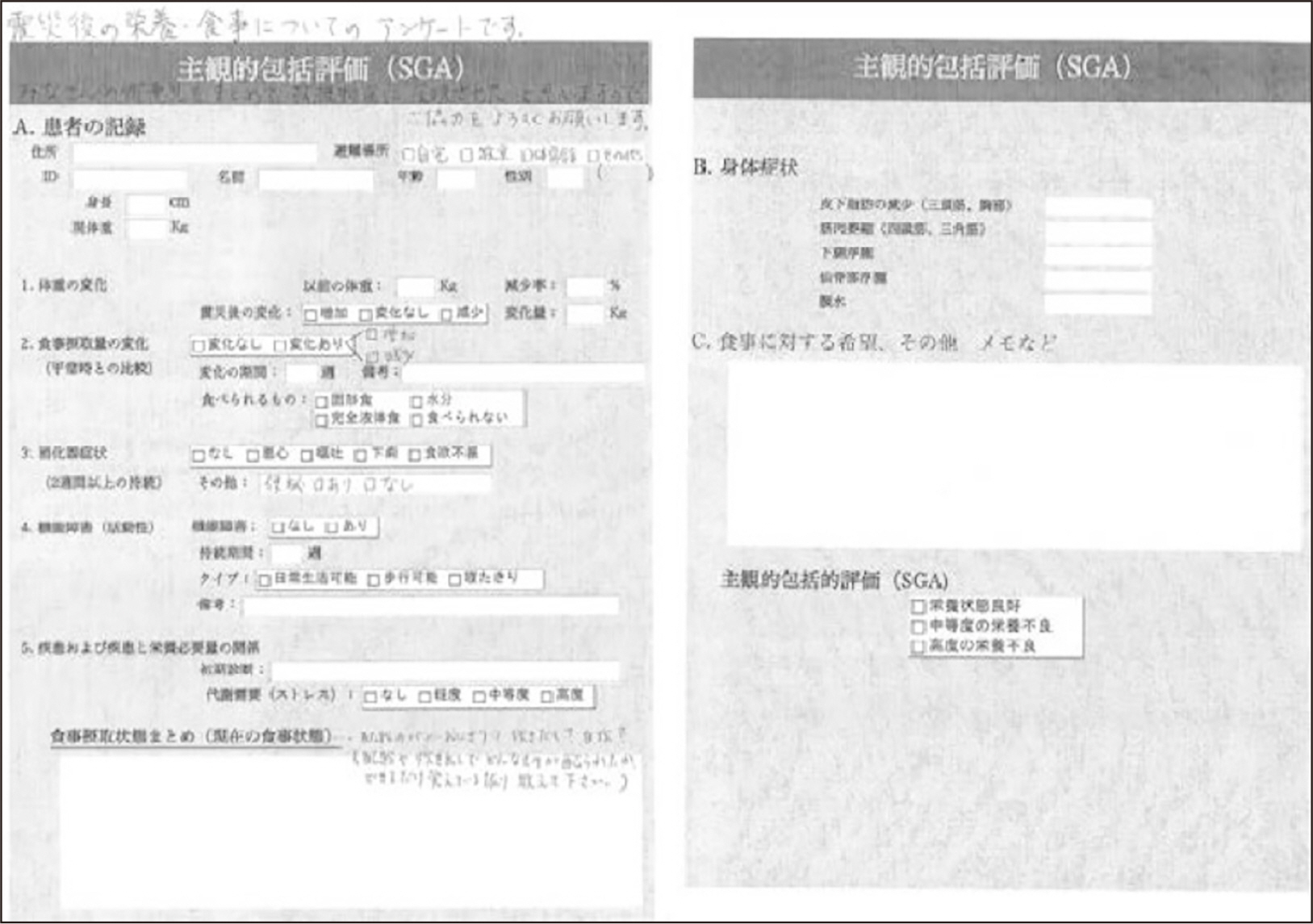

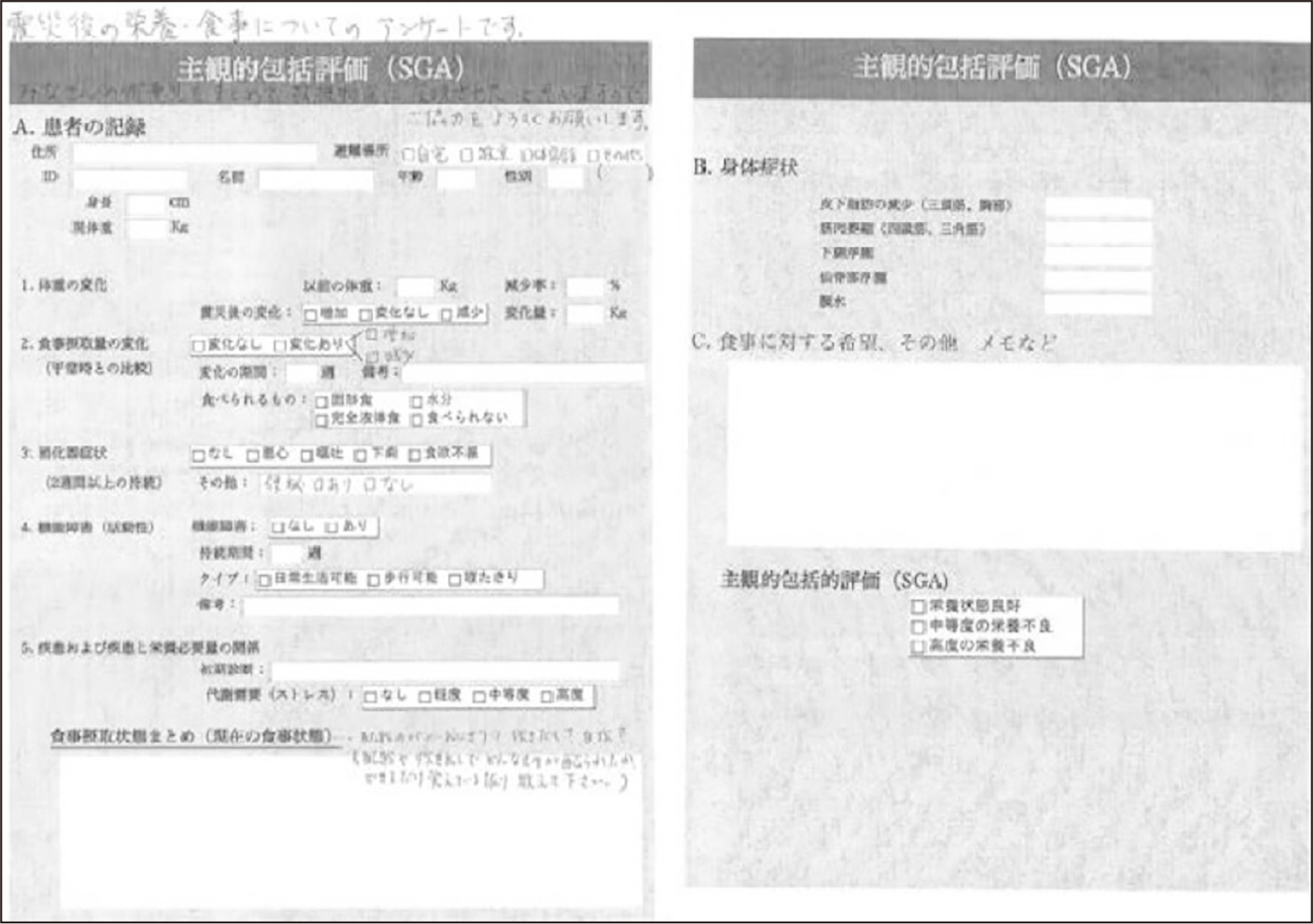

Questionnaire: A SGA form was used (

Fig. 2).

Results

Differences between shelters and convalescent homes

Atmosphere (Fig. 3)

In the shelter, there were complaints such as lack of privacy due to the absence of partitions and the smell of other people’s food throughout the surroundings. Additionally, because there were no tables and people had to sit on the floor to eat, several people complained of pressure to their upper abdomen and loss of appetite. The lack of a power supply meant that there was no refrigerator, making it impossible to store ice cream, preserved foods, and other items. The overall atmosphere was one of “endurance”. On the other hand, the atmosphere in the nursing home was lively and bright.

The living environment was similar to daily life for residents, and they were generally healthy and cheerful.

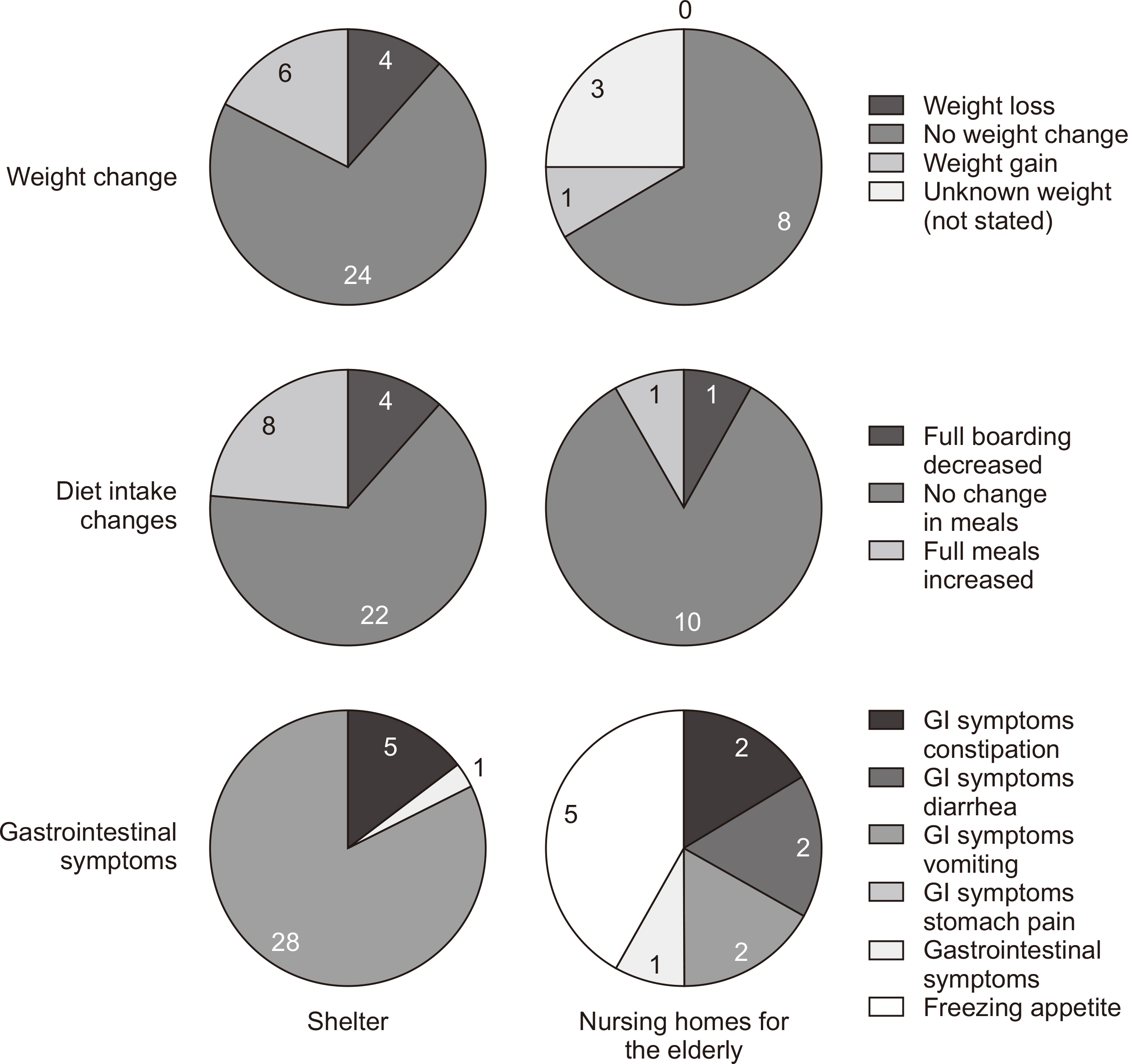

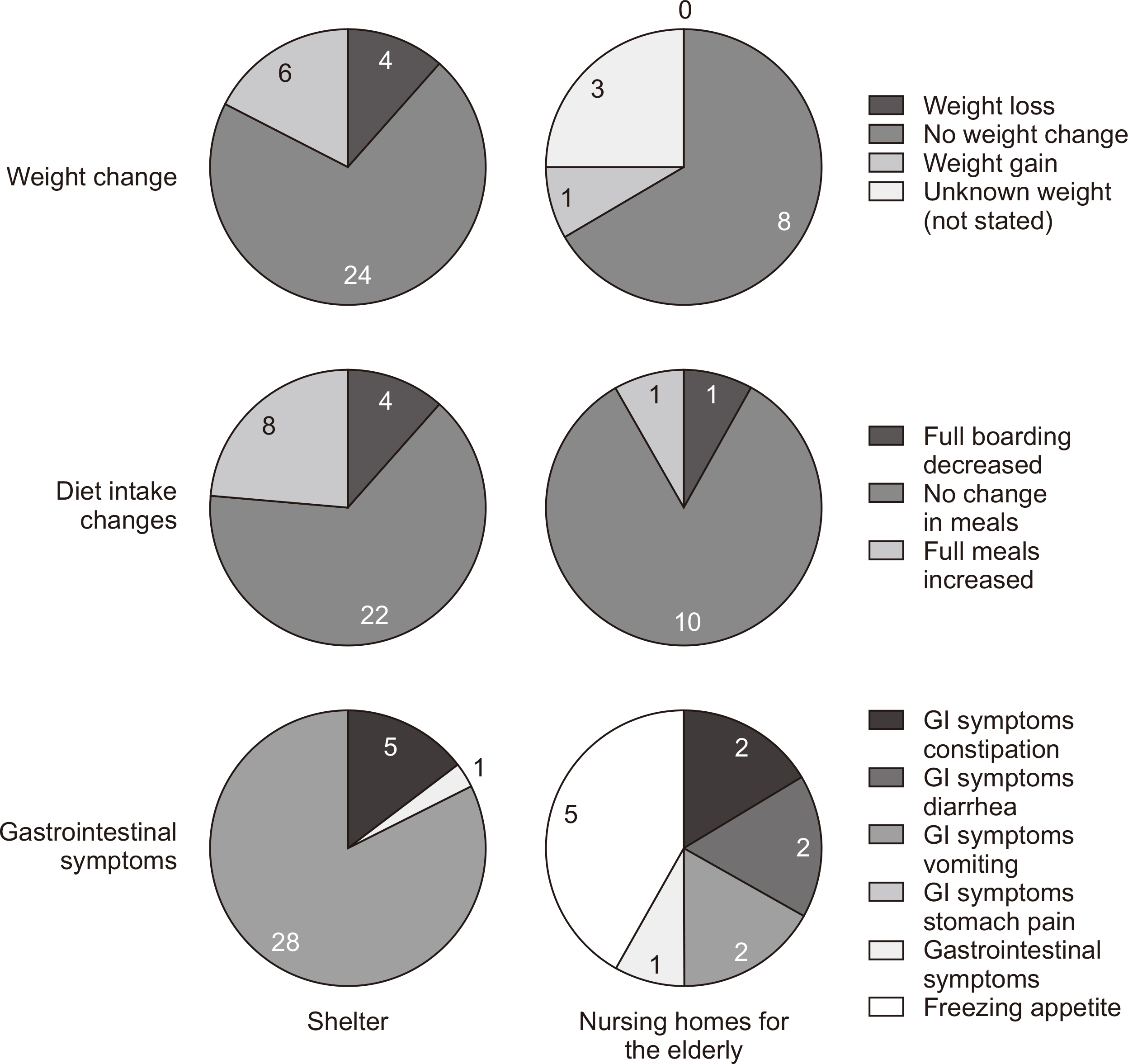

Weight change (Fig. 4)

More than half the residents in both the evacuation shelters and the sanatoriums did not change their weight. Those who lost weight had stayed in the evacuation shelters, but not in the sanatoriums.

Change in food intake (Fig. 4)

Many people did not experience weight changes in either the evacuation shelters or the sanatoriums. However, many people gained weight in the evacuation shelters. There are several explanations.

Much of the food brought to shelters was high calorie.

People were thankful for the food, and felt it was polite to eat everything and leave no leftovers. People said things like:

“I eat sweets because they are there.”

“I eat it even after a meal if there is a cup noodle.”

Gastrointestinal symptoms (Fig. 4)

Many people in the evacuation centers were asymptomatic, but constipation was the most common symptom. This may reflect the low consumption of vegetables and the high consumption of carbohydrates. In contrast, a “greater variety of symptoms were observed in the sanatoriums. This may reflect the fact that the patients were elderly.

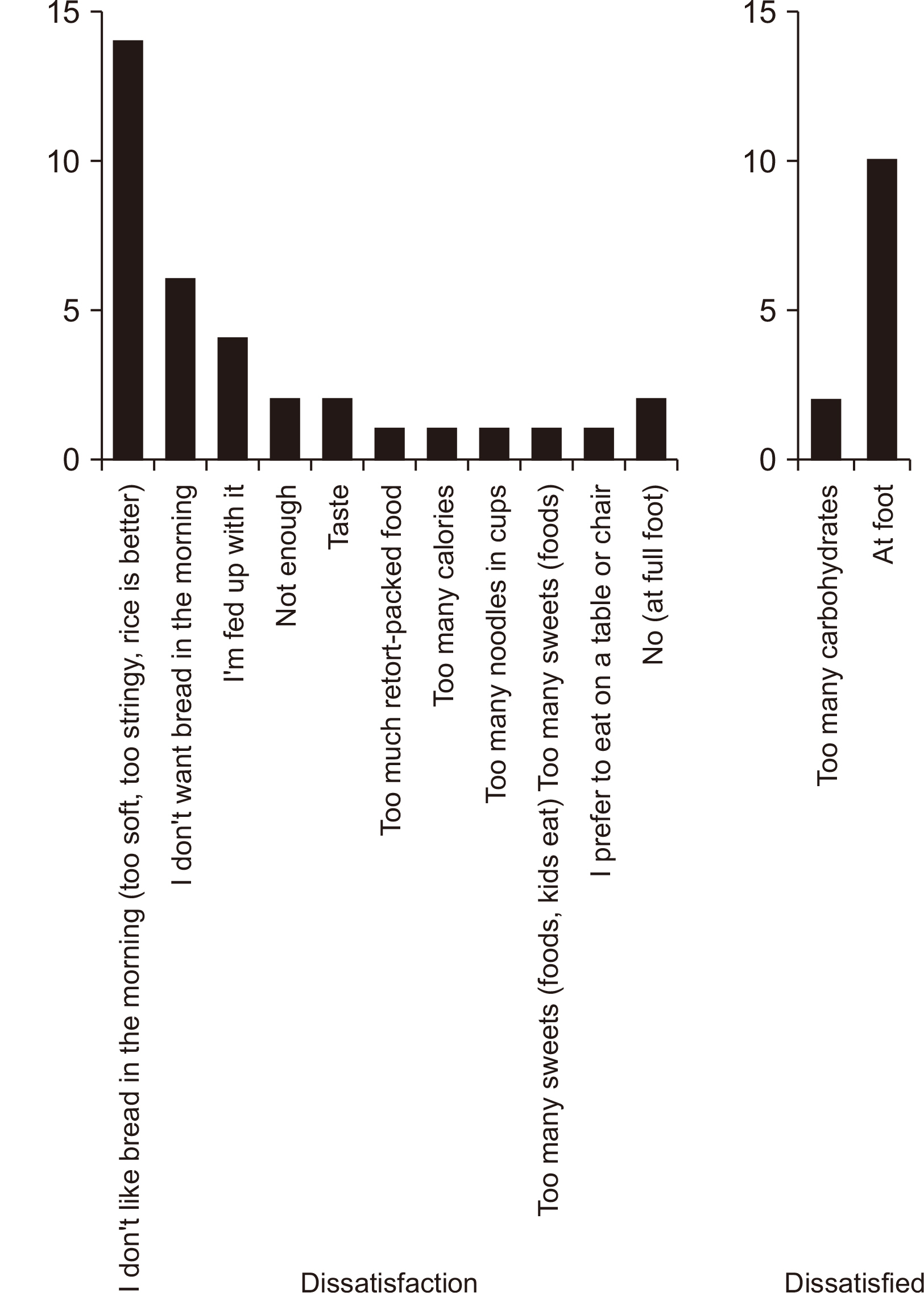

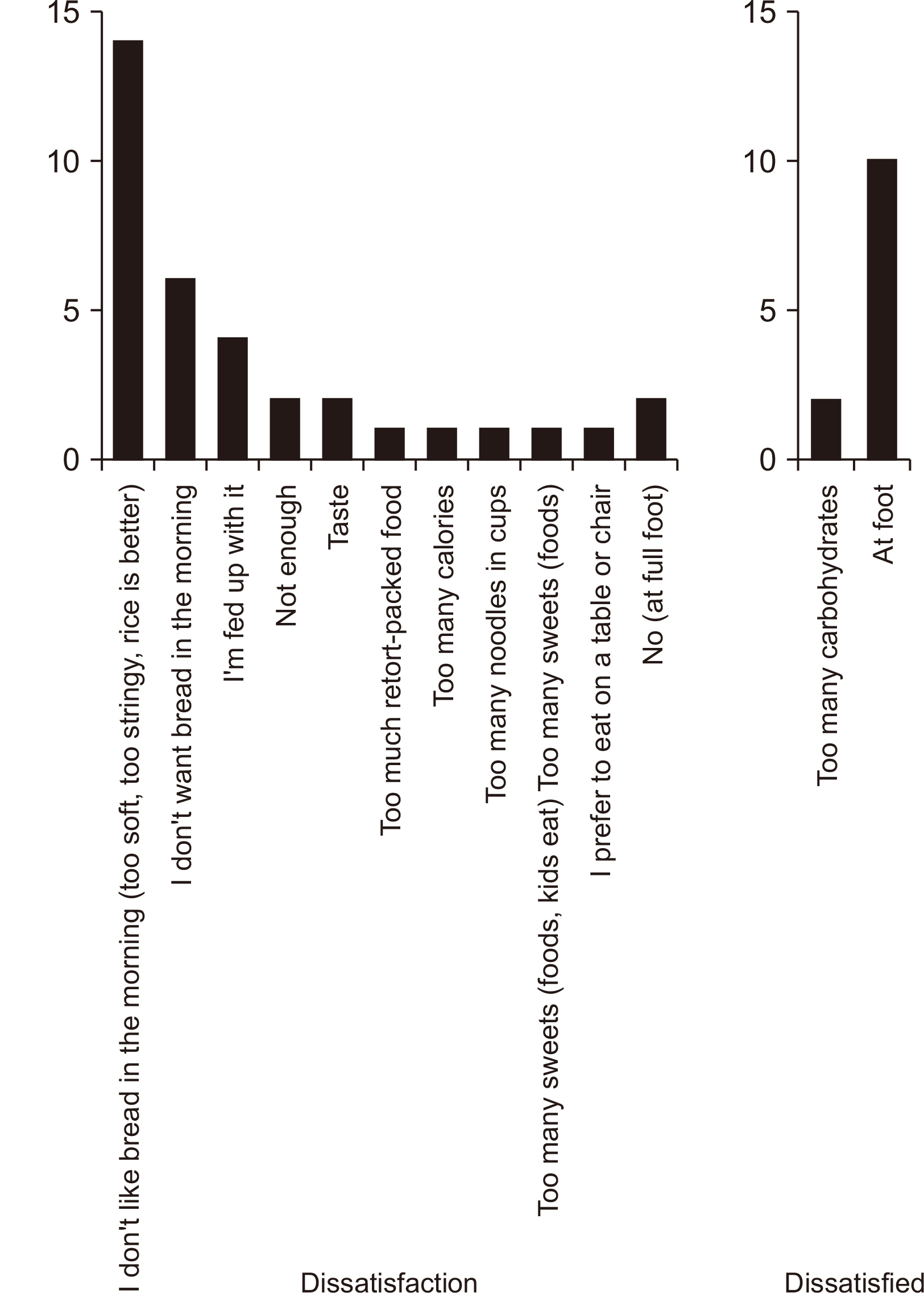

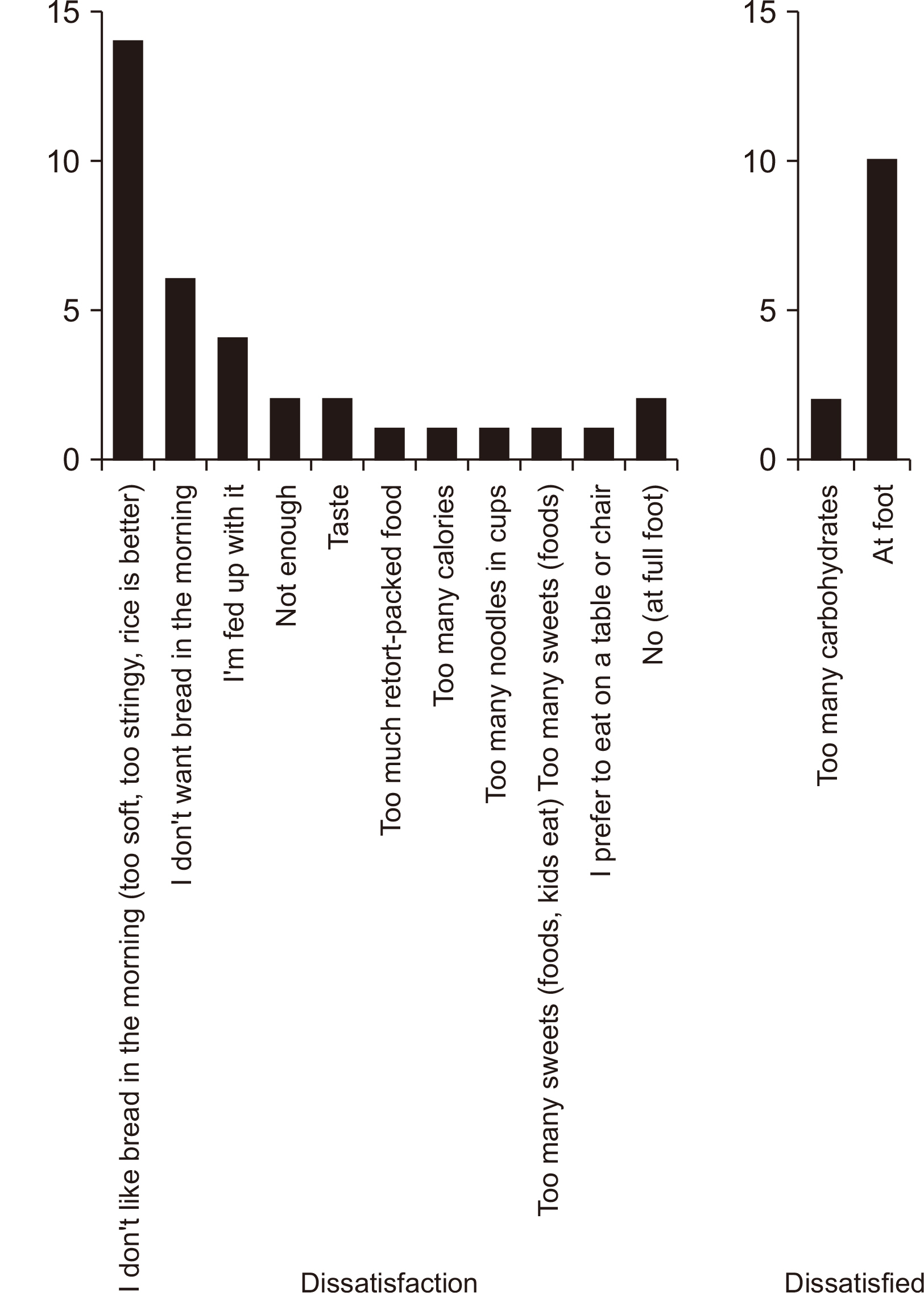

Complaints (Fig. 4)

In the shelters, only two respondents reported no dissatisfaction, while many others complained of dissatisfaction. The reasons for dissatisfaction were diverse. In the sanitorium, the majority of respondents had no complaints and were highly satisfied with the food.

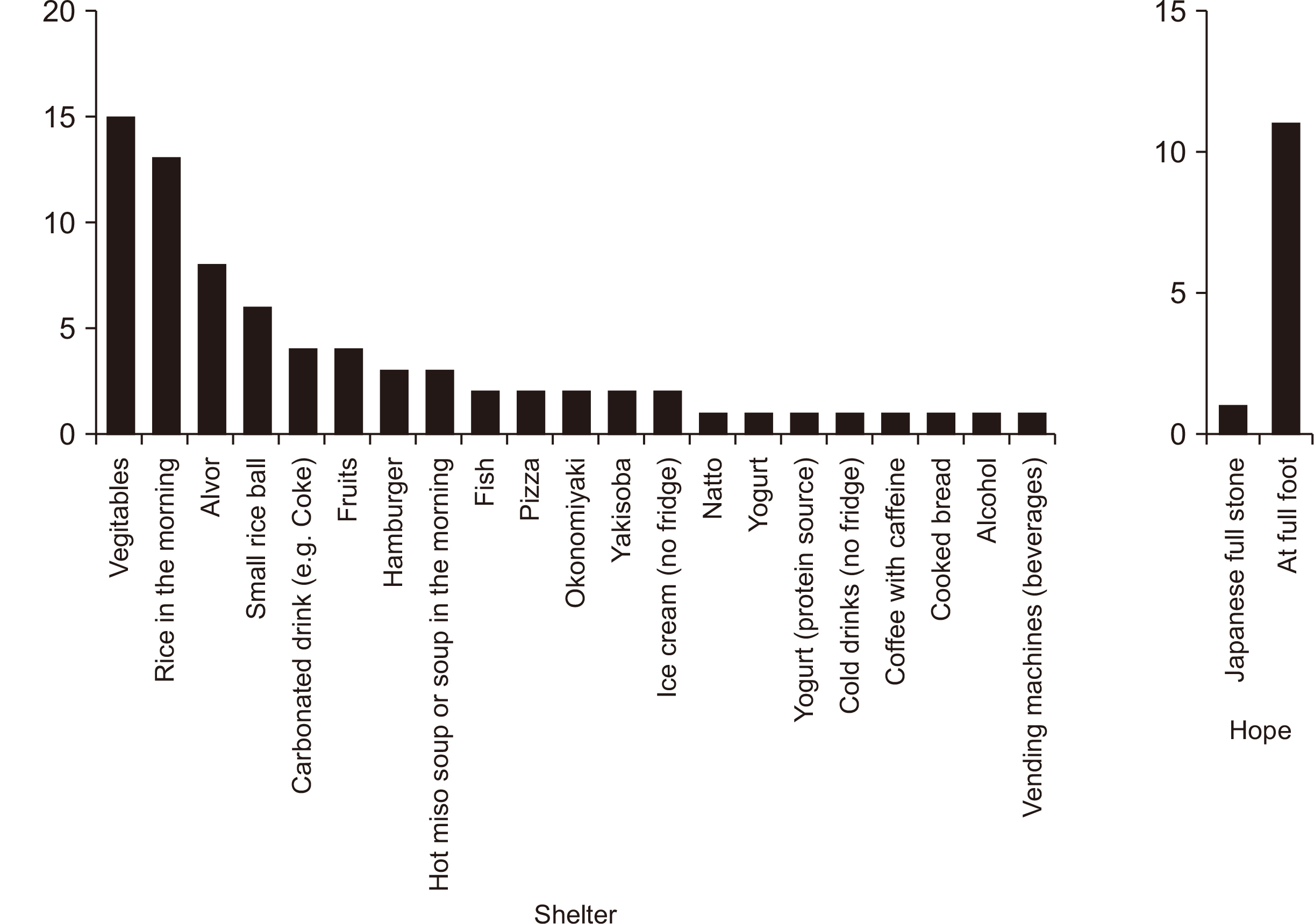

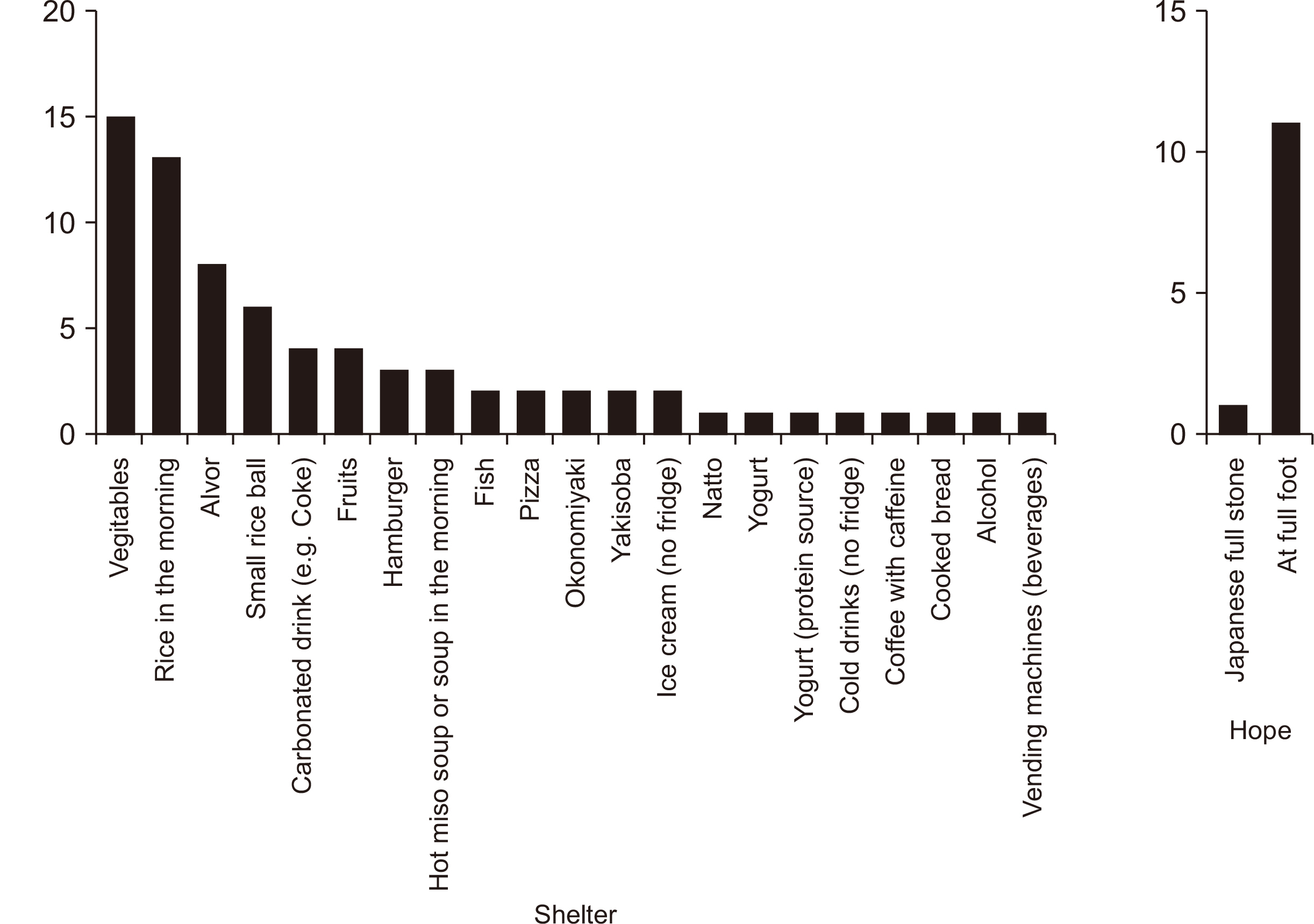

The survey also investigated hope, which is the opposite of dissatisfaction. Contrary to dissatisfaction, we also conducted a survey on food preferences.

In the refugee center, all the respondents expressed their preferences. In the sanatorium, one person expressed a desire to eat Japanese food, but this was a desire to try a luxurious meal, not a dissatisfaction. All but one answered “no wish,” indicating a high level of satisfaction with the meals. In fact, when the author interviewed people at the sanatorium, it was impressive that many of them answered “satisfied” with the food with a smile on their face.

Dietary situation at the evacuation center (shelter): dissatisfaction and hope, problems

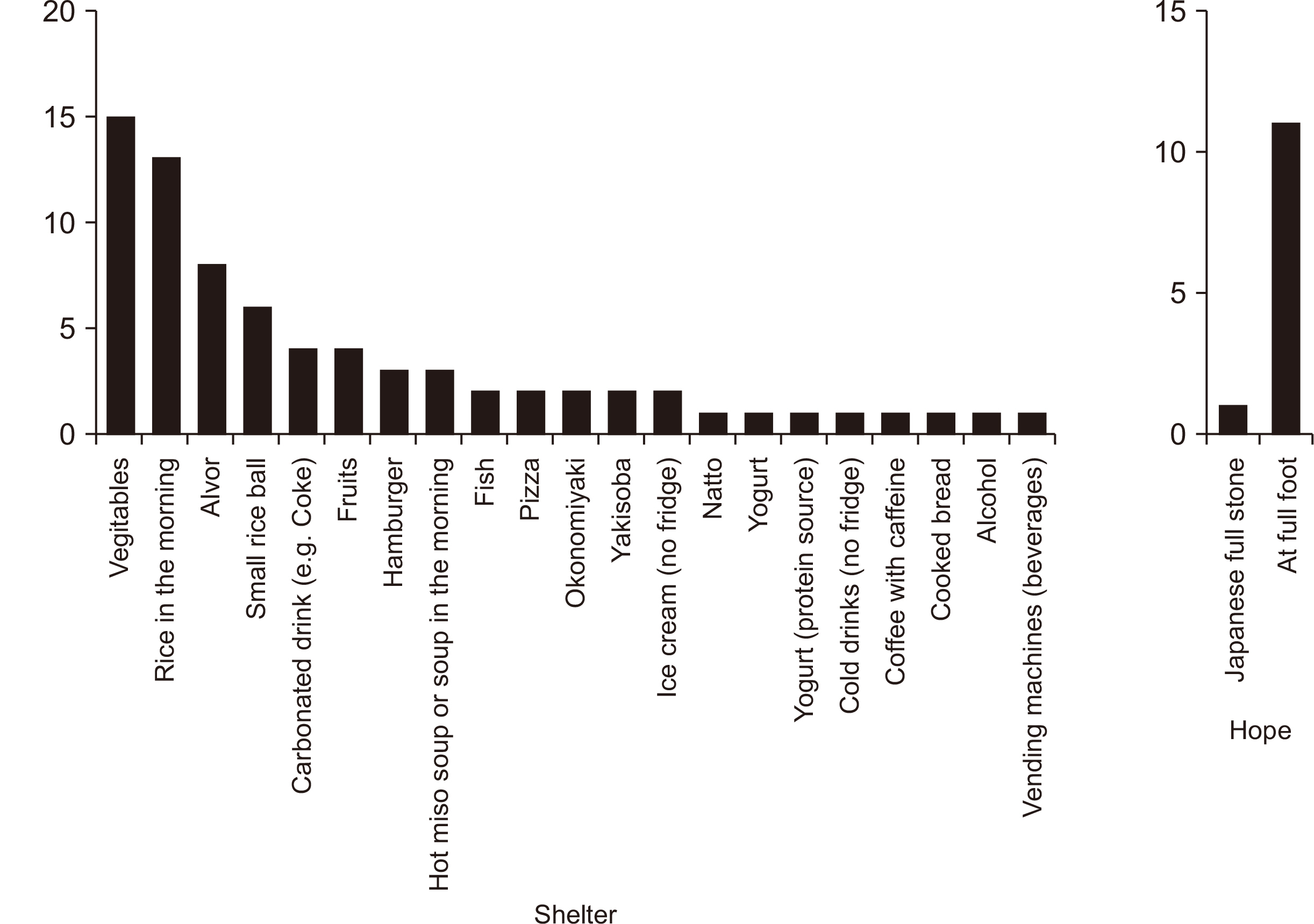

Figs. 5 and

6 summarize “dissatisfaction” and “hope” in the questionnaire. The following is a list of specific examples of dissatisfaction, their causes, and countermeasures, including some of the evacuees’ comments during the author's questionnaire survey.

Breakfast

The most common complaint was about the morning bread. The most common complaints were “too sweet,” and “I'm too hungry.” Additionally, there were many farmer evacuees who said they wanted to eat “rice and miso soup” instead of bread in the morning.

The bread distributed for breakfast was mostly sweet pastries, and many of them were just before their expiration date. This may be because sweet bread has a relatively long shelf life, and the expiration date of sweet bread approaches during delivery (

Fig. 7D).

There were several respondents who said that they could eat dry bread (there were no complaints about dry bread served at the nursing homes) (

Fig. 7F).

There were multiple complaints about the morning beverages, such as “the juice is cold” and “I want something warm” (

Fig. 7C).

Lack of vegetables

The most common wish was “I want vegetables.” At the time, there was information that norovirus infection had spread from vegetables, and it was difficult to get vegetables in the market.

Therefore, there was a shortage of vegetables in the evacuation centers. Interestingly, evacuees with kidney failure were provided with plastic-packed “low-potassium vegetables” for personal use. This type of individually packaged vegetables would be a good option for distribution to the general public.

Excessive carbohydrates

Breakfast was mostly bread, and lunch and dinner were onigiri (rice balls). There was a bias toward carbohydrates among the three major nutrients.

Onigiri rice balls made by the Self-Defense Forces are made by putting rice in a plastic bag and handing it to the evacuees, but they are quite large (

Fig. 7A, B). Evacuees called them “SDF rice,” and “bomb rice” for example. Some evacuees said they had to eat all the food.

Young people in particular often ate cup noodles between meals.

Constipation was the most common gastrointestinal symptom, which may reflect excessive carbohydrate intake.

(In fact, the author experienced severe constipation after consuming only bread and rice balls for the first three days of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, when the university hospital provided only bread and rice balls for the first three days.)

Lack of variety and diet choice

The third most common complaint was “boredom” especially with pastries and juice.

The food items provided were bread and juice in the morning, and onigiri (rice balls), retort-pouch foods, and cup noodles, which have a long shelf life, for lunch and dinner.

Many respondents stated, “In the early stages of living in the shelter, I was very thankful for the food that was brought in, but from around the second week, I became bored with the food.”

They started asking for a variety of meals, such as yakisoba, okonomiyaki, pizza (which was potentially available), and ice cream (which was not available because there was no refrigerator).

There were many requests for canned coffee, which quickly went out of stock when it was brought in.

The people who sent the food to the evacuation centers may have been satisfied with the food they sent without giving much thought to the needs of the people in the shelters.

The people who provide food for the evacuees may be satisfied with the food they send, without considering the preferences of the evacuees. Anther common comment from participants was: “I want a vending machine where I can choose what I want.” When we think about daily life, a large part of the enjoyment of eating is getting to choose what to eat. Providing choices for meals at evacuation centers may help reduce the stress of evacuees.

Unexpected

One person said, “I want to eat at a table with chairs.”

The rescuers were so concerned about what kind of food to bring in that they did not pay attention to the eating conditions. All the evacuees were sitting on the floor, which can be a difficult position. The NST suggested to the headquarters that desks and chairs be placed outside when it gets warmer.

Ice cream, cold drinks, and yogurt were requested especially by young women. However, if sweets and desserts were available, it could have alleviated some of the complaints of boredom with the food. It would have been better to have a refrigerator in the shelter.

The younger family members generally had access to transportation, such as a car, and were able to go outside to buy what they wanted, but they complained that they had to eat the food they bought immediately because there was no refrigerator, and that they could not store it.

There was a difference in food availability depending on the age group. The elderly generally had difficulty with mobility and were unable to go shopping on their own. Thus, they ate only rationed foodstuffs.

Surprisingly, only one respondent expressed a need for alcohol.

Others

The most common complaints were that the food was too strong-tasting, especially for the Self-Defense Forces meals and retort-pouch foods.

A mother complained, “I can’t stop my child from eating sweets all the time.”

Diabetics: In general, blood glucose monitoring was not conducted. In general, diabetic patients did not have their blood sugar measured, and they also ate a lot of food without too much concern because it was an emergency situation.

Dialysis patients: Normally, it takes 20 minutes to go to the dialysis hospital, but after the earthquake, it took two hours to go to the hospital because of the bridge collapse. The food and water restrictions at the evacuation center alone were quite stressful, but hospital visits also added to the stress.

Reasons for the less of dissatisfaction and hope

The source of the food supplies were neighbors and remote nursing homes, so the needs of the nursing homes were known and the food supplies were based on these needs.

The foodstuffs were selected based on these needs. As a result, there were no dietary problems at all.

The food source knew the needs of the nursing home and selected the foodstuffs based on these needs.

Breakfast was bread, but no sweets (

Fig. 7F).

This situation was in stark contrast to the situation in the evacuation center.

Adaptation to living environment

Residents of the sanatorium who experienced the evacuation center said, “It is as different as heaven and hell,” suggesting that the environment of the evacuation center was inferior.

Some people were sleeping at the time of the earthquake and had forgotten that there had been an earthquake because of dementia.

The atmosphere in the sanatorium was cheerful, and the residents were generally energetic and cheerful (

Fig. 3B), suggesting that the residents who survived to old age may have been physically and mentally robust to begin with.

Discussion

In addition to medical care, Takahashi et al. [

2] suggest that disaster survivors in disaster areas should: (1) avoid emotional stress, (2) eat meals at regular times, (3) wash their hands, (4) gargle, and disinfect cooking utensils to prevent enteritis. In a survey conducted after the Great East Japan Earthquake, we reported that gastrointestinal symptoms, especially constipation, were common among evacuees, probably due in part to the high carbohydrate content of the food items provided, and that evacuees had preferences regarding the food items they were provided. However, issues related to foodstuffs and the environment in which they are consumed have not yet been clearly identified.

Issues related to food ingredients and the environment in which they are consumed have not been clarified until now.

In this study, we investigated the dietary situation in evacuation centers and sanatoriums after the Kumamoto earthquake and summarized the comparative results. In the sanatoriums, the food was supplied by the same sanatorium in a remote area and by neighboring farmers who knew the needs of the residents. As a result, the residents of the sanatoriums were eating similar to their normal diet, and their satisfaction was remarkably high. On the other hand, in the evacuation shelters, the suppliers did not seem to know or consider the preferences of the evacuees, and they were more likely to eat carbohydrates such as rice balls and breads. The evacuees were too thankful for the food supplies to express their dissatisfaction, and after two weeks, they were gradually approaching the end of their patience and requested a variety of food items. Therefore, it seems that the choice of food to be brought to the evacuation centers should be based on the needs of the evacuees, and it would be very beneficial for the evacuees to be exposed to this through interventions such as the SGA survey. Because eating, along with bathing, is the most important part of daily life, food interventions may be effective, not only in terms of nutrition, but also in terms of mental health.

Acknowledgments

None.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: JK. Data curation: JK. Formal analysis: JK. Investigation: JK, IY, TU. Methodology: JK, IY, TU. Project administration: JK, IY, TU. Resources: JK, IY, TU. Software: JK. Supervision: JK. Validation: JK, IY, TU. Visualization: JK, IY, TU. Writing – original draft: JK. Writing – review & editing: all authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

None.

Data availability

None.

Supplementary materials

None.

Fig. 1Nutrition Support Team (NST) organization positioning in the April 29, 2016, organizational chart. NSTs were established across the four districts.

Fig. 2Survey form for Subjective Comprehensive Assessment (SGA), which is routinely used in hospitals where Nutrition Support Teams (NSTs) were active. SGA routinely used in hospital NSTs was used.

Fig. 3Difference in food situation between shelters and convalescent home. (A) Food situation in shelters. Providers: dependent on supplies from remote areas. No bulkheads: no privacy, smells are transmitted. No table, no chairs: sitting on the floor to eat. No refrigerator (no power): ice cream, preserves, etc. not available. The overall atmosphere is one of “endurance”. (B) Food situation in convalescent home. The food situation in the nursing home. Living environment: exactly the same as in daily life.

Fig. 4Results of the Subjective General Assessment. GI = gastrointestinal.

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7Differences in food ingredients between shelters and sanatoriums. (A) Onigiri (shelter: Minamiaso Junior High School): supplied by the Self-Defense Forces. Rice balls were made by putting rice in a plastic bag and wringing it out. (B) Onigiri (shelter: Hakusui Town Hall): Same as (A). (C) Morning juice (shelter: Minamiaso Junior High School): the same juice was supplied every day. Some evacuees said they were bored and wanted something warm to drink in the morning. (D) Morning bread (shelter: Minamiaso Junior High School): generally, sweet pastries were the most common (and would probably last for a long time). Many of them are just before the expiration date (it takes time to distribute). The second bread from the right was an exception. The second three-meal loaf of bread from the right is an exception. (E) Vegetables (sanatorium: Hibari): sent from nearby farmers and remote sanatoriums. Cardboard boxes were piled up (abundant). (F) Morning bread (sanatorium: Hibari): relatively light. It has a sufficient expiration date (

Fig. 7C).

References

- 1. Inoue T, Nakao A, Kuboyama K, Hashimoto A, Masutani M, Ueda T, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and food/nutrition concerns after the great East Japan earthquake in March 2011: survey of evacuees in a temporary shelter. Prehosp Disaster Med 2014;29:303-6. ArticlePubMed

- 2. Takahashi T, Iijima K, Kuzuya M, Hattori H, Yokono K, Morimoto S. Guidelines for non-medical care providers to manage the first steps of emergency triage of elderly evacuees. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2011;11:383-94. ArticlePubMed

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

Cite

Cite