Scopus, KCI, KoreaMed

Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Clin Nutr > Volume 13(1); 2021 > Article

- Original Article Vitamin D Deficiency is Prevalent in Short Bowel Syndrome Patients on Long-Term Parenteral Nutrition Support

-

SungHyo An1

, Sanghoon Lee1,2

, Sanghoon Lee1,2 , Hyun-Jung Kim2

, Hyun-Jung Kim2 , Hyo Jung Park2

, Hyo Jung Park2 , Jeong-Meen Seo1,2

, Jeong-Meen Seo1,2

- 단장증후군으로 장기간 정맥영양공급을 받는 환자에서 비타민 D 결핍

-

안성효1

, 이상훈1,2

, 이상훈1,2 , 김현정2

, 김현정2 , 박효정2

, 박효정2 , 서정민1,2

, 서정민1,2

-

Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2021;13(1):12-16.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15747/jcn.2021.13.1.12

Published online: June 30, 2021

1Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

2Intestinal Rehabilitation Team, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- Correspondence to Sanghoon Lee https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5086-1461Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan UniversitySchool of Medicine, 81 Irwon-ro, Gangnam-gu, Seoul 06351, KoreaTel: +82-2-3410-4025, Fax: +82-2-3410-0040, E-mail: hooni4@skku.edu

© 2021, The Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. All Rights Reserved.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,891 Views

- 6 Download

- 1 Crossref

Abstract

-

Purpose Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is the most common etiology for intestinal failure (IF) and these patients are at high risk of developing micronutrient deficiencies. This study aimed at assessing the level of vitamins in adult SBS patients at different stages of their disease before the initiation of multidisciplinary intestinal rehabilitation.

-

Methods Patient data from November 2015 to March 2017 were retrospectively reviewed. Adult patients who underwent extensive bowel resection and were classified as SBS-IF were selected. Clinical data including age, sex, etiology of IF, biochemical data, nutritional status, nutrition support, and outcome of intestinal rehabilitation were analyzed.

-

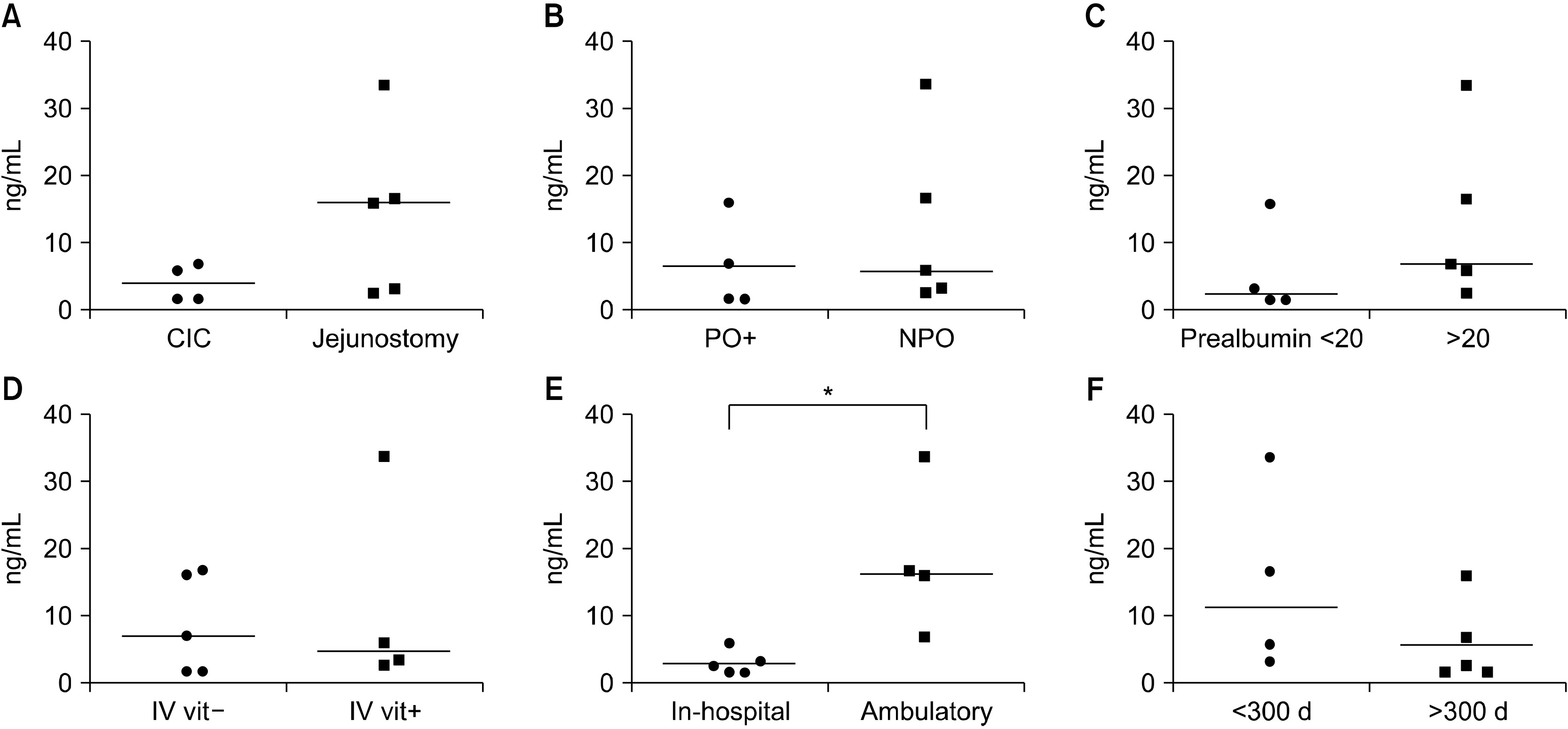

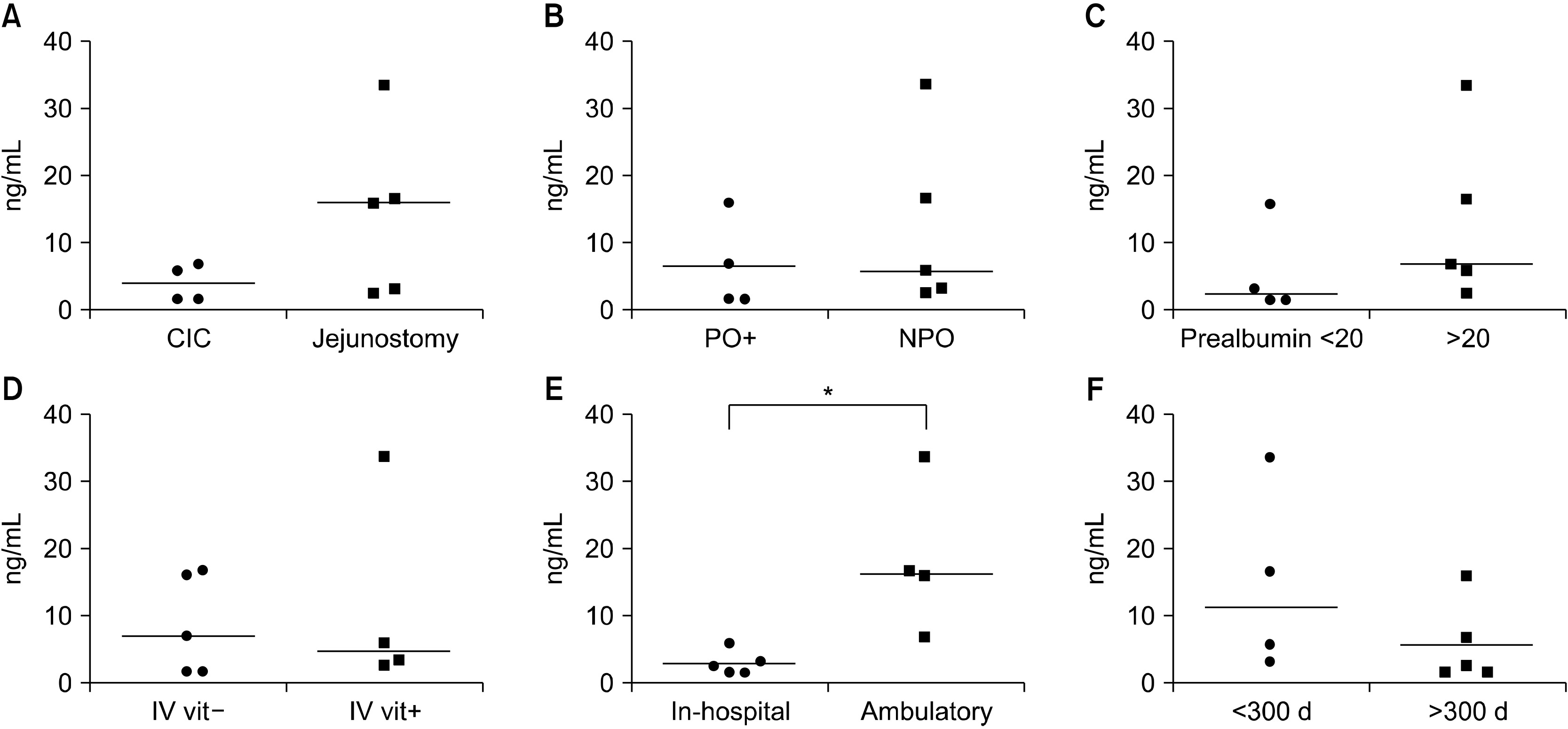

Results Nine patients with SBS-IF were included in the analysis. There were 6 male patients and 3 female patients, with a median age of 55.0 years. Vitamin levels were analyzed at 306 days (median) after the development of SBS. At the time of vitamin levels screening, 4 patients were receiving daily intravenous vitamin supplementation. Five patients were not receiving vitamin supplementations, either intravenously or orally. Vitamin B12 was within the normal range in 6 patients and higher than normal in 3 patients. Vitamin D was within the normal range in 3 patients and lower than normal in 6 patients. Vitamin E was within the normal range in 7 patients and higher than normal in 2 patients. Folate was within the normal range in 8 patients (not checked in 1 patient). Ambulatory patients had significantly higher vitamin D levels compared to hospitalized patients (P=0.015).

-

Conclusion Vitamin D levels had decreased in 67% of patients with SBS in Korea, while vitamin B12, folate, and vitamin E deficiencies were rarely seen.

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

- 1. Thompson JS. 2000;Comparison of massive vs. repeated resection leading to short bowel syndrome. J Gastrointest Surg 4(1):101-4. ArticlePubMed

- 2. Pironi L, Arends J, Baxter J, Bozzetti F, Peláez RB, Cuerda C, et al. 2015;ESPEN endorsed recommendations. Definition and classification of intestinal failure in adults. Clin Nutr 34(2):171-80. ArticlePubMed

- 3. Schalamon J, Mayr JM, Höllwarth ME. 2003;Mortality and economics in short bowel syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 17(6):931-42. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Ubesie AC, Kocoshis SA, Mezoff AG, Henderson CJ, Helmrath MA, Cole CR. 2013;Multiple micronutrient deficiencies among patients with intestinal failure during and after transition to enteral nutrition. J Pediatr 163(6):1692-6. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Wimalawansa SJ. 2011;Vitamin D: an essential component for skeletal health. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1240:E1-12. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Yang CF, Duro D, Zurakowski D, Lee M, Jaksic T, Duggan C. 2011;High prevalence of multiple micronutrient deficiencies in children with intestinal failure: a longitudinal study. J Pediatr 159(1):39-44.e1. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Thomson P, Duerksen DR. 2011;Vitamin D deficiency in patients receiving home parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 35(4):499-504. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 8. Yoon S, Lee S, Park HJ, Kim HJ, Yoon J, Min JK, et al. 2018;Multidisciplinary intestinal rehabilitation for short bowel syndrome in adults: results in a Korean intestinal rehabilitation team. J Clin Nutr 10(2):45-50. Article

- 9. Feng H, Zhang T, Yan W, Lu L, Tao Y, Cai W, et al. 2020;Micronutrient deficiencies in pediatric short bowel syndrome: a 10-year review from an intestinal rehabilitation center in China. Pediatr Surg Int 36(12):1481-7. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 10. Modi BP, Langer M, Ching YA, Valim C, Waterford SD, Iglesias J, et al. 2008;Improved survival in a multidisciplinary short bowel syndrome program. J Pediatr Surg 43(1):20-4. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Diamond IR, de Silva N, Pencharz PB, Kim JH, Wales PW. 2007;Neonatal short bowel syndrome outcomes after the establishment of the first Canadian multidisciplinary intestinal rehabilitation program: preliminary experience. J Pediatr Surg 42(5):806-11. ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- A narrative inquiry into the disease adaptation experience of long-term follow-up patients with short bowel syndrome in Korea

Eun-Mi Seol, Eunjung Kim

Ann Clin Nutr Metab.2025; 17(3): 188. CrossRef

Fig. 1

Patient demographics

| Sex | Age (y) | Days from SBS to referral | Bowel anatomy | PN dependence (%) | Prealbumin (20∼40 mg/dL) | Vitamin supplementation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 45 | 701 | Jejunoileal anastomosis | 80 | 10.3 | None |

| 2 | F | 58 | 390 | Jejunocolic anastomosis | 80 | 18.8 | None |

| 3 | F | 43 | 108 | Jejunoileal anastomosis | 50 | 8.6 | None |

| 4 | M | 58 | 2,234 | Jejunoileal anastomosis | 50 | 23.9 | None |

| 5 | M | 67 | 39 | Jejunoileal anastomosis | 100 | 27.7 | Intravenous |

| 6 | M | 51 | 90 | Jejunostomy | 100 | 9.9 | Intravenous |

| 7 | M | 55 | 8 | Jejunostomy | 100 | 27.1 | None |

| 8 | F | 57 | 45 | Jejunostomy | 100 | 27.6 | Intravenous |

| 9 | M | 21 | 314 | Jejunostomy | 100 | 23.3 | Intravenous |

M = male; F = female; SBS = short bowel syndrome; PN = parenteral nutrition.

Initial vitamin analysis results

| Days from SBS to vitamin analysis | Vitamin B12 (160∼970 pg/mL) | Vitamin D (10∼150 ng/mL) | Vitamin E (11.6∼46.4 umol/L) | Folate (1.5∼16.9 ng/mL) | INR (0.9∼1.1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 721 | 852.0 | 1.8 | 15.1 | 5.3 | NA |

| 2 | 391 | 2,925.0 | 16.0 | 15.2 | 5.5 | 1.01 |

| 3 | 306 | 1,529.0 | 1.8 | 24.7 | 7.5 | 1.24 |

| 4 | 2,545 | 174.0 | 7.0 | 28.9 | 15.0 | 1.02 |

| 5 | 89 | 853.0 | 6.0 | 52.8 | 9.5 | 1.11 |

| 6 | 91 | 764.0 | 3.4 | 36.5 | 1.5 | 1.20 |

| 7 | 11 | 529.0 | 16.7 | 36.7 | 6.6 | 1.20 |

| 8 | 54 | 338.0 | 33.5 | 32.0 | NA | 0.99 |

| 9 | 319 | 4,460.0 | 2.7 | 62.4 | 14.8 | 1.41 |

SBS = short bowel syndrome; INR = international normalized ratio; NA = not available.

Composition of intravenous multi-vitamin concentrate (Tamipool®) and daily requirement of vitamins

| Unit | TamipoolⓇ | Daily requirement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A | IU | 3,300 | 3,300 |

| Vitamin D | IU | 200 | 200 |

| Vitamin E | IU | 10 | 10 |

| Vitamin K | mcg | 0 | 150 |

| Vitamin C | mg | 100 | 200 |

| Thiamine | mg | 3.4 | 6 |

| Riboflavin | mg | 2.8 | 3.6 |

| Niacin | mg | 40 | 40 |

| Pantothenic acid | mg | 15 | 15 |

| Pyridoxine | mg | 4.0 | 6 |

| Cyanocobalamin | mcg | 5 | 5 |

| Biotin | mcg | 60 | 60 |

| Folic acid | mcg | 400 | 600 |

M = male; F = female; SBS = short bowel syndrome; PN = parenteral nutrition.

SBS = short bowel syndrome; INR = international normalized ratio; NA = not available.

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN Cite

Cite