Abstract

-

Purpose:

The aim of this study was to elucidate the patterns of calorie support during the immediate postoperative period following a gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients.

-

Materials and Methods:

The clinicopathologic characteristics and nutritional parameters, including the actual infused amount of calories during the immediate postoperative period, were retrospectively collected and analyzed, This was data from a total 1,390 cases out of 1,404 patients who underwent curative gastrectomy at Samsung Medical Center, from Jan. 1 2016 through Dec. 31, 2016.

-

Results:

The actual infused amount of calories during the immediate postoperative period (the first three days following surgery) was only 41.6% of the recommended average intake of calories, which was significantly lower (759.8±139.4 kcal/day vs 1,825.7±251.6 kcal/day, respectively). The target calories supply per unit body weight was 30 kcal/kg. According to the operative method, the average infused amount of calories was lower in open gastrectomy compared to when utilizing the minimal invasive methods (laparoscopic assisted or robot assisted gastrectomy) (742.11 kcal/day:11.7 kcal/kg vs 792.95 kacl/day:12.8 kcal/kg or 791.43 kcal/day:12.8 kcal/kg, respectively). In regards to the operative type, the average infused amount of calories was higher in subtotal gastrectomy compared to that in total gastrectomy (732.1 kcal/day:12.23 kcal/kg vs 689.5 kcal/day:11.7 kcal/kg, respectively). The female group had a higher calorie supply per unit body weight compared to that of the male group (766.0 kcal/day:13.7 kcal/kg vs 758.9 kcal/day:11.3 kcal/kg, respectively). According to body mass index (BMI), the low BMI group had a lower calorie intake compared to that of the normal or high BMI group (700.2 kcal/day:15.3 kcal/kg vs 761.8 kcal/day:13.6 kcal/kg vs 766.5 kcal/day:11.1 kcal/kg, respectively). The actual infused amount of calorie significantly varied day by day in all the groups (range: 31.52 kcal/day to 1,559.31 kcal/day).

-

Conclusion:

The actual calorie intake significantly varied from day-to-day. Moreover, the intake was significantly lower than the average daily recommended amount of calories following a gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients during the immediate postoperative period.

-

Keywords: Gastric cancer; Gastrectomy; Nutrition support

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common malignant disease worldwide and the second most common cause of death from cancer.[

1] Despite chemotherapy is prolonging survival in cases of advanced disease, radical curative gastrectomy has been known as the most effective treatment for curable gastric cancer.[

2] Weight loss was reported in 31∼87% of patients at first diagnosis of malignancy, with a weight loss of more than 10% being observed in 15% of all patient within a 6 month period prior to diagnosis.[

3,

4] Patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC) were at particular risk from malnutrition, as they were more susceptible to anorexia-cachexia syndrome induced by decreased food intake, hypoalbuminemia, weight loss, muscle tissue wasting, and mechanical obstruction effects of the upper digestive tract (dysphagia, nausea, vomiting), and were also associated with increased morbidity and mortality.[

5-

9]

There is a high risk of malnutrition after a gastrectomy which may be attributed to inadequate oral consumption, malabsorption, rapid intestinal transit time, and loss of the reservoir function of the stomach.[

10,

11] Even following the acute post-operative period, the risk of malnutrition may be associated with a diet based on frequent small meals and limitation of simple carbohydrates in order to prevent dumping syndrome, the decline of appetite resulting in decreased diet intake.[

12,

13] Furthermore, post-operative chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy may also contribute to cancer-related malnutrition.[

14-

16]

Malnutrition was also an independent risk factor for postoperative mortality and morbidity in major gastrointestinal surgery with an increased incidence rate of postoperative complications.[

17,

18] Accordingly, it highlights the utmost importance for clinicians to choose an appropriate form of nutritional therapy for patients during recovery following gastric cancer surgery and to promote the rehabilitation of patients.[

19,

20]

Supplementary parenteral nutrition (SPN), one of nutrition providing method, is to minimize the lack of calories during the period of protein and nutrient supply less than 60% below the target through the per oral or enteral feeding.[

21] Each guideline has different guidelines on when to start SPN. SPN starting time is 7∼10 days after hospitalization in American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN),[

22] and it depends on each patient’s condition but recommended starting within 7 days after hospitalization in European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN).[

23]

In gastrectomized patients, malnutrition could increase the rate of infection, hospital day, and morbidity.[

12] Moreover, 10∼30% of weight loss was common after gastrectomy,[

3,

4] so it is reasonable to provide calories to gastrectomized patients during immediate post-operative period.

Although there are a number of studies regarding long-term changes to the nutritional status of patients following a gastrectomy, there have been few reports surrounding nutritional support in the immediate postoperative period after undergoing a gastrectomy.

The aim of the study was to elucidate the patterns of calories support during the immediate postoperative period following a gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study population

This retrospective study included a total of 1,404 gastric cancer patients who underwent curative gastrectomy between the period of January, 2016 to December, 2016 at the Samsung Medical Center (SMC), Seoul, Republic of Korea. The collected data was then retrospectively reviewed and analyzed.

Patients were diagnosed via esophagogastroduodenoscopy with biopsy, and abdominal computed tomography scans. In addition, endoscopic ultrasonography was applied as was occasional required.

Ethical issues and patients consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) (file No. 2019-03- 037-001). Data were collected on clinicopathologic characteristics of patients, nutritional parameters including body weight change, serologic parameters, and the actual amount of infused fluid day by day up to the 3rd post-operative day (POD#3).

Patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), gastric neuroendocrine tumor, other cancers (esophageal cancer, breast cancer, duodenal bulb cancer) were excluded, and patients who underwent a second-operation in the immediate post-operative period (up to POD#3) were also excluded.

2. Nutrition assessment

The nutritional support team (NST) in SMC who used nutritional risk screening (NRS) 2002, assessed the nutrition risk status of patients and recommended daily calorie intake amounts.

The NST checked the nutritional risk factors of all admitted patients and routinely suggested daily-recommended calories.

3. Surgical procedure

All patients underwent subtotal or total gastrectomy depending on the location of the tumor. Subtotal gastrectomy requires the use of a distal subtotal gastrectomy, while the reconstructive surgeries included Billroth I, Billroth II, and Roux-en-Y depending on patient’s condition and/or the surgeon’s preferences. The total gastrectomy group included a completion total gastrectomy which resulted from a previous subtotal gastrectomy. All patients underwent surgery performed by six surgeons in Samsung Medical Center.

The operation method consisted of an open method with no laparoscopic instrument, a laparoscopic method, and a robotic method using da Vinci®.

4. Protocols for perioperative management

Post-operative management was kept by SMC clinical pathway (CP). Following surgery, all patients were admitted to the general surgical ward. Dietary consumption started with sips of water on the 4th day following open surgery and on the 3rd day after laparoscopic/robotic surgery. During the fasting period, a 5% or 10% dextrose solution with nutrition supporting fluids (amino acid solution or lipid solution) was infused following SMC CP (

Table 1).

Table 1Clinical pathway (CP) of Samsung medical center for nutritional support after gastrectomy

|

Dextrose 5% |

Dextrose 10% |

Hepasol®

|

Smoflipid® 20% |

|

<Open method> |

|

|

|

|

|

POD # -1 (SOW) |

2 L |

|

|

|

|

Op. day (NPO) |

1 L (pre-Op.) |

1 L (post-Op.) |

|

|

|

POD # 1 (NPO) |

|

2 L |

0.5 L |

|

|

POD # 2 (NPO) |

|

2 L |

|

0.5 L |

|

POD # 3 (NPO) |

|

2 L |

0.5 L |

|

|

POD # 4 (SOW) |

|

2 L |

|

0.5 L |

|

POD # 5 (SFD) |

2 L |

|

|

|

|

POD # 6 (SBD1) |

PRN |

|

|

|

|

POD # 7 (SBD2) |

|

|

|

|

|

<Laparoscopic method> |

|

|

POD # -1 (SOW) |

2 L |

|

|

|

|

Op. day (NPO) |

1 L (pre-Op.) |

1 L (post-Op.) |

|

|

|

POD # 1 (NPO) |

|

2 L |

0.5 L |

|

|

POD # 2 (NPO) |

|

2 L |

|

0.5 L |

|

POD # 3 (SOW) |

|

2 L |

0.5 L |

|

|

POD # 4 (SFD) |

2 L |

|

|

|

|

POD # 5 (SBD1) |

PRN |

|

|

|

|

POD # 6 (SBD2) |

|

|

|

|

5. Postoperative Intravenous (IV) infused calorie analysis

Among the data of daily input/output, non-calorie fluid was excluded and actual the infused amount of calories was calculated using a caloric fluid table (

Table 2). Under the premise of both Hepasol

® and Smoflipid

® 20% fluid was infused, while the amount of remained fluid was compared to the amount of prescribed fluid. The ratio of the actual infused amount of each caloric fluid relative to the total prescribed caloric fluid was calculated, and the infused amount of calories categorized by each caloric fluid was also calculated.

Table 2Amount of calories in the infused fluid

|

Total volume (ml/bag) |

Total calorie (kcal/bag) |

|

Dextrose-saline |

|

|

|

Dextrose 5% |

1,000 |

187 |

|

Dextrose 10% |

1,000 |

374 |

|

Amino acid solution |

|

|

|

Hepasol®

|

500 |

180 |

|

Lipid solution |

|

|

|

Smoflipid® 20% |

500 |

1,000 |

|

Commercial parenteral nutrition |

|

|

|

Peri Olimel N4E®

|

1,000 |

700 |

|

SmofKabiven® peri |

1,448 |

1,006 |

|

SmofKabiven® central |

1,970 |

2,154 |

|

Winuf® peri |

2,020 |

1,396 |

|

Winuf® central |

1,435 |

1,566 |

6. Statistics

All statistical analyses were done using SPSS statistics software version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

A comparison between the groups was done via a t-test, and a significance level of 0.05 was used; reported P-values were 2-tailed.

RESULTS

1. Patients

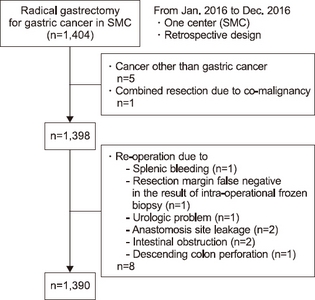

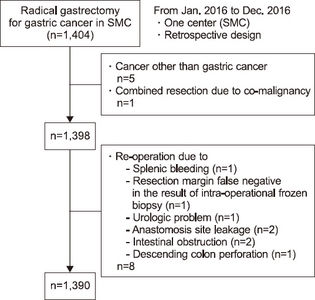

Between January 1 2016 and December 31 2016, a total of 1,404 patients who underwent curative gastrectomy were included in the study (

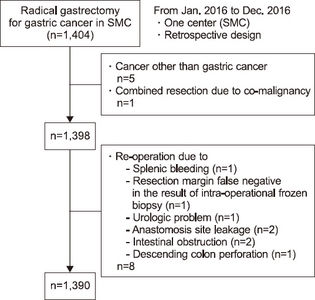

Fig. 1). Fourteen patients out of the 1,404 were excluded as a result of the discovery of other cancers or because of the need for reoperation during the immediate post-operation period. Six patients were also excluded as they were not diagnosed as having gastric cancer (2 cases of GIST, 1 case of duodenal bulb cancer, 1 case of gastric neuroendocrine tumor, 1 case of distal esophageal cancer, and 1 case having double primary cancer in the breast). Moreover, eight patients were ineligible because of the requirement of a reoperation in the immediate post-operation period (2 cases due to an anastomosis leak, 1 case due to ureter injury, 1 case due to splenic bleeding, 2 cases due to intestinal obstruction, 1 case due to descending colon perforation, and 1 case as a result of a false negative in the intra-operational frozen biopsy).

Fig. 1Disposition of the patients.

2. Status of intravenous calorie support

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the included patients have been summarized in

Table 3. While the recommended amount of mean calorie intake during the immediate postoperative period (up to three post-operative days) was 28.6±2.5 kcal/kg and 1,825.7±251.6 kcal/day, the average amount of infused calories amounted to 12.1±2.8 kcal/kg and 759.8±139.4 kcal/day. The range of infused calories/day varied from day-to-day; ranging from 31.52 kcal/day to 1,559.31 kcal/day (

Table 4). The actual infused calorie intake amounted to 41.6% of the recommended calorie intake, which was significantly lower.

Table 3Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients

|

Variables |

Patients analyzed (n=1,390) |

|

Age (years) |

58.8±11.5 (22.0~95.0) |

|

Sex |

|

|

Male |

911 (65.5%) |

|

Female |

479 (34.4%) |

|

ASA score |

|

|

1 |

449 (32.3%) |

|

2 |

880 (63.3%) |

|

3 |

60 (4.3%) |

|

4 |

1 (0.1%) |

|

Operation method |

|

|

Open |

835 (60.07%) |

|

Laparoscopic |

499 (35.90%) |

|

Robotic |

56 (4.03%) |

|

Operation type |

|

|

STG BI |

756 (54.39%) |

|

STG BII |

273 (19.64%) |

|

STG RY |

24 (1.73%) |

|

TG |

318 (22.88%) |

|

cTG |

19 (1.36%) |

|

Combined resection |

|

|

No |

1,254 (90.2%) |

|

Yes |

136 (9.8%) |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

23.9±3.1 (15.42~37.44) |

|

PNI |

44.2±3.5 |

Table 4Infused calorie for postoperative three days

|

Infused calorie |

Recommended* calorie |

|

Kcal/kg |

12.1±2.81 |

28.1±2.5 |

|

Kcal/day |

759.8±139.4 |

1,825.7±251.6 |

|

Range : 31.52 kcal/day to 1,559.31 kcal/day |

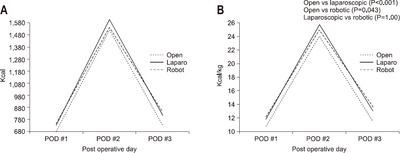

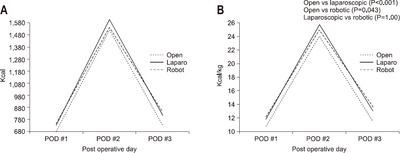

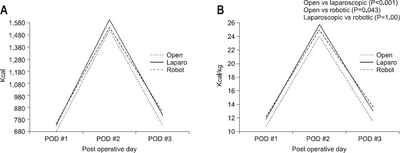

According to results from variations in operative methods, the average amount of calories consumed in the case of the open method was 742.11 kcal/day and 11.7±2.8 kcal/kg, 792.95 kcal/day and 12.8±2.8 kcal/kg in the laparoscopic method, and 791.43 kcal/day and 12.8±2.4 kcal/kg in the robotic method, respectively. The actual infused intravenous calories in the open method was significantly lower than that of the laparoscopic method (P<0.001) and the robotic method (P=0.043). There was no significant difference between the laparoscopic method and the robotic method (P=1.00). The average infused amount of calories was lower in open gastrectomy compared to that of the minimal invasive method (

Fig. 2).

Fig. 2The actual supported intravenous calories according to operation method. (A) Total calorie amount/day. (B) Calorie/kg/day.

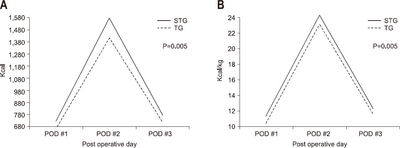

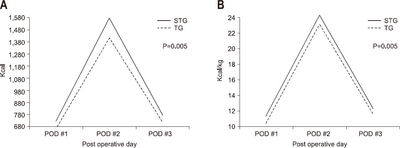

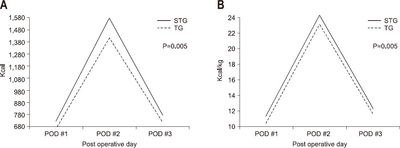

According to the operative type, the average amount of calories consumed was 732.1 kcal/day and 12.2±2.8 kcal/kg, in the subtotal gastrectomy group and 689.5 kcal/day and 11.7±2.8 kcal/kg in the total gastrectomy group, respectively. The average infused amount of calories was higher in subtotal gastrectomy than in total gastrectomy (P=0.005) (

Fig. 3).

Fig. 3The actual supported intravenous calories according to operation type. (A) Total calorie amount/day. (B) Calorie/kg/day.

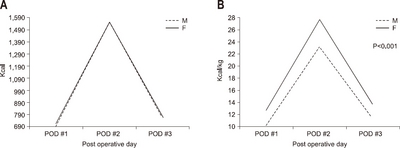

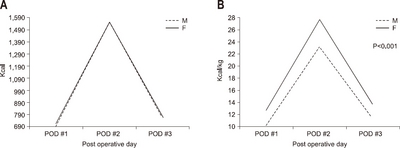

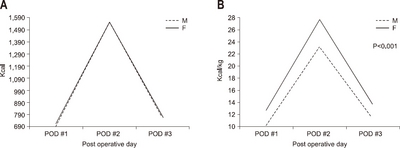

According to gender, the average amount of calories consumed was 758.9 kcal/day and 11.3±2.6 kcal/kg in the male group, and 766.0kcal/day and 13.7±2.6 kcal/kg in the female group, respectively. The female group had a higher calorie supply per unit body weight than the male group (P<0.001) (

Fig. 4).

Fig. 4The actual supported intravenous calories according to gender. (A) Total calorie amount/day. (B) Calorie/kg/day.

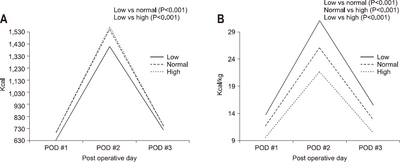

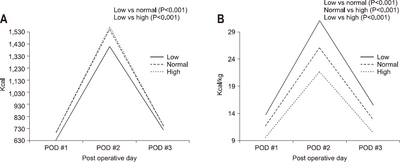

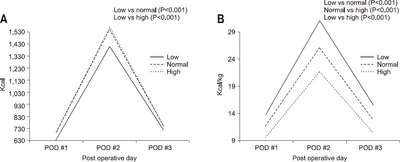

According to body mass index (BMI), the average amount of calories consumed was 700.2 kcal/day and 15.3±2.4 kcal/kg in the low BMI group (under 18.5 kg/m

2), 761.8 kcal/day, and 13.6±2.6 kcal/kg in the normal BMI group (18.5 kg/m

2 to 24.9 kg/m

2), and 766.5 kcal/day and 11.1±2.5 kcal/kg in the high BMI group (over 25.0 kg/m

2), respectively. The actual infused calories per body weight in the low BMI group was higher than that in the normal BMI group (P<0.001) or the high BMI group (P<0.001). The normal BMI group showed higher actual infused calories per body weight than in the high BMI group (P<0.001) (

Fig. 5)

Fig. 5The actual supported intravenous calories according to BMI. (A) Total calorie amount/day. (B) Calorie/kg/day.

DISCUSSION

In surgical patients, poor nutritional support was highly associated with major postoperative morbidity, cancer recurrence, re-operations, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and hospital re-admissions.[

24] In spite of predicted significant weight loss after all types of gastrectomy,[

25] peri-operative nutrition was a vital but often overlooked aspect of surgical care.[

26]

Following a gastrectomy, oral intake until recovery of bowel movements is restricted, although the early recovery after surgery (ERAS) program has recently recommended early oral feeding in the immediate postoperative period.[

27] There have been a number of reports surrounding parenteral or enteral nutritional support for ICU patients with serious conditions or long- term hospitalized patients with complications.[

28-

30]

It was, however, very hard to find reports in literature concerned with nutritional support in the immediate postoperative period, especially following a gastrectomy.

It was assumed that the amount of calories supplied in clinical practice during that period or the prescribed calorie amount by critical pathway differed from the recommended calorie intake amount. Thus, it would make an interesting and informative study for clinical practice to investigate the actual calorie amounts utilized for nutritional support in patients after a gastrectomy.

In our study, actual calorie intake significantly varied day-to-day (31.52 kcal/day to 1,559.31 kcal/day), and was much lower than the recommended amount of calories following a gastrectomy for gastric cancer patients during the immediate postoperative period. It was especially interesting that the prescribed calorie amount was much lower than recommended calorie intake, which was only 41.6% per body weight, and 42.3% per day of recommended calorie intake.

This difference between the prescribed calorie amount and the recommended calorie amount can be explained by the Clinical pathway (CP) of our institute targeting patients weighing 60 kg without considering the individual’s body weight and nutritional risk. Daily variable actual calorie intake can result from differences in the amount of calories in amino acid solutions (Hepasol®, 180 kcal/bag) and lipid solutions (Smoflipid® 20%, 1,000 kcal/bag) used alternately every day as a supplement in the Clinical pathway (CP). Thus, it is necessary to modify the clinical pathway which should include the infused fluid and calories based on the weight and nutritional risk of an individual, and to supply amino acid solution and lipid solution evenly every day or use a solution which contains both amino acid and lipid in the Clinical pathway (CP) program.

When comparing operation method, patients in the open method were found to have had a lower calorie intake than those in the laparoscopic method and the robotic method. There were no significant differences found between the laparoscopic method and the robotic method. Differences in calorie support between the open method group and the minimal invasive method groups (laparoscopic/robotic) may have resulted from differences in dietary intake build up times. The minimal invasive group started oral consumption one day prior to the open method group in the clinical pathway.

According to the type of operation, the subtotal gastrectomy group included reconstructive procedures Billroth I, Billroth II, and Roux-en-Y anastomosis, and was shown to have had higher infused amounts of calories than the total gastrectomy group which included completion of a total gastrectomy. The difference in calorie support between subtotal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy might have also resulted from differences in dietary intake build up times. The subtotal gastrectomy group started oral consumption one day prior to the total gastrectomy group via the clinical pathway.

There is no significant difference in the total amount of calories supplied per day between the male and female group. However, the female group was found to have had a higher calories supply per unit body weight compared to that of the male group. It is hard to specifically describe the cause of difference in calorie supply between the male and female group, but it was assumed that the male group had higher body weight than the female group, and more frequently underwent the open method or a total gastrectomy due to more advanced status of disease or a higher positioning of the stomach.

The low BMI group had a lower total calorie supply than normal BMI group and the high BMI group, but the low BMI group had a higher calories supply per unit body weight than the normal BMI and high BMI group. Likewise, the normal BMI group had a higher calories supply per unit body weight than the high BMI group. This resulted from the fact that calculated calories were based on the body weight of the patient, thus the lower BMI group had to be given less calories than the normal or high BMI group, and that recommended calories were calculated from an ideal body weight, which resulted in the higher BMI group having a lower calorie supply compared to real body weight.

These differences can also be explained by that Clinical pathway (CP) of our institute which catered to a generalized 60 kg weight. Therefore, the relatively high weighted groups (male group and high BMI group) were supplied a lower amount of calories per unit body weight.

It is likely that nutritional support is sometimes provided without considering the individual’s body weight and nutritional risk.

It is suggested that a sufficient amount of calories should be supplied after a gastrectomy for patients, and that calorie supply should be individualized according to the condition of each patient. Clinical pathway (CP) of our institute needs to be changed to reflect the individual’s body weight and nutritional risk.

It may also be suggested that small amounts of calories may be appropriate in immediate postoperative period after gastric surgery, and that revision may be necessary to the exact amount of calories which should be given in a certain period of time following gastric surgery.

Our study had some limitations. First, there were limited follow up days in the immediate post-operative period (up to three days after surgery), which is a short period to gain significant results. Second, our study only calculated intravenous supplied calories. However, it was very difficult to calculate the calorie intake after the 3rd. postoperative day as patients started oral consumption which varied according to the individual patient and was not recorded precisely. There were only input/output amounts in medical records making it nearly impossible to determine the amount consumed (i.e. oral calorie intake) on the SFD (Soft Fluid Diet) and SBD (Soft Bland Diet) after a period of fasting, NPO (Nothing Per Oral), during post-operative management.

Thus, future research should focus on the total amount of supplied calories to patients during the full-term of the post-operative period with exact records showing exactly how much patients eat and how much calories supplied through SFD and SBD by date. Furthermore, through objective laboratory tests, examining albumin levels, lymphocyte count, transferrin amount, etc., it is possible to investigate tendencies of PNI index changes or results of other laboratory tests according to calorie supply, and thus yield a new index of which is more appropriate for nutritional strategy.

In conclusion, the actual calorie intake was significantly variable day-to-day, and was found to have been much lower than the recommended amount of calories which should be given after a gastrectomy for gastric cancer patients during the immediate postoperative period.

References

- 1. Shen L, Shan YS, Hu HM, Price TJ, Sirohi B, Yeh KH, et al. Management of gastric cancer in Asia:resource-stratified guidelines. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e535-47. ArticlePubMed

- 2. Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, Kurokawa Y, Nashimoto A, Kurita A. Japan Clinical Oncology Group D2 lymphadenectomy alone or with para-aortic nodal dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 2008;359:453-62. ArticlePubMed

- 3. Deans DA, Tan BH, Wigmore SJ, Ross JA, de Beaux AC, Paterson- Brown S, et al. The influence of systemic inflammation, dietary intake and stage of disease on rate of weight loss in patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer 2009;100:63-9. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 4. Ravasco P, Monteiro-Grillo I, Vidal PM, Camilo ME. Cancer:disease and nutrition are key determinants of patients'quality of life. Support Care Cancer 2004;12:246-52. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia:an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:489-95. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Tan CR, Yaffee PM, Jamil LH, Lo SK, Nissen N, Pandol SJ, et al. Pancreatic cancer cachexia:a review of mechanisms and therapeutics. Front Physiol 2014;5:88.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Evans WJ, Morley JE, Argilés J, Bales C, Baracos V, Guttridge D, et al. Cachexia:a new definition. Clin Nutr 2008;27:793-9. ArticlePubMed

- 8. Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT, Band PR, Bennett JM, Bertino JR, et al. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Med 1980;69:491-7. ArticlePubMed

- 9. Donohoe CL, Ryan AM, Reynolds JV. Cancer cachexia:mechanisms and clinical implications. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2011;2011:601434.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 10. Hillman HS. Postgastrectomy malnutrition. Gut 1968;9:576-84. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Radigan AE. Post-gastrectomy:managing the nutrition fall-out. Pract Gastroenterol 2004;18:63-75.Article

- 12. Rosania R, Chiapponi C, Malfertheiner P, Venerito M. Nutrition in patients with gastric cancer:an update. Gastrointest Tumors 2016;2:178-87. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 13. Ryu SW, Kim IH. Comparison of different nutritional assessments in detecting malnutrition among gastric cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:3310-7. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Tong H, Isenring E, Yates P. The prevalence of nutrition impact symptoms and their relationship to quality of life and clinical outcomes in medical oncology patients. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:83-90. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 15. Van Cutsem E, Arends J. The causes and consequences of cancer-associated malnutrition. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2005;9(Suppl 2):S51-63. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Shahmoradi N, Kandiah M, Peng LS. Impact of nutritional status on the quality of life of advanced cancer patients in hospice home care. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2009;10:1003-09. ArticlePubMed

- 17. Heneghan HM, Zaborowski A, Fanning M, McHugh A, Doyle S, Moore J, et al. Prospective study of malabsorption and malnutrition after esophageal and gastric cancer surgery. Ann Surg 2015;262:803-7. ArticlePubMed

- 18. Fernández-Sordo JO, Konda VJ, Chennat J, Madrigal-Hoyos E, Posner MC, Ferguson MK, et al. Is Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) necessary in the pre-therapeutic assessment of Barrett's esophagus with early neoplasia? J Gastrointest Oncol 2012;3:314-21. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Chen W, Zhang Z, Xiong M, Meng X, Dai F, Fang J, et al. Early enteral nutrition after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2014;23:607-11. ArticlePubMed

- 20. Wang J, Zhao J, Zhang Y, Liu C. Early enteral nutrition and total parenteral nutrition on the nutritional status and blood glucose in patients with gastric cancer complicated with diabetes mellitus after radical gastrectomy. Exp Ther Med 2018;16:321-7. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Oshima T, Heidegger CP, Pichard C. Supplemental parenteral nutrition is the key to prevent energy deficits in critically ill patients. Nutr Clin Pract 2016;31:432-7. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 22. McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, Braunschweig C, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient:Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016;40:159-211. ArticlePubMed

- 23. Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Alhazzani W, Calder PC, Casaer MP, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr 2019;38:48-79. ArticlePubMed

- 24. Kathiresan AS, Brookfield KF, Schuman SI, Lucci JA 3rd. Malnutrition as a predictor of poor postoperative outcomes in gynecologic cancer patients. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;284:445-51. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 25. van der Beek ES, Monpellier VM, Eland I, Tromp E, van Ramshorst B. Nutritional deficiencies in gastric bypass patients;incidence, time of occurrence and implications for post-operative surveillance. Obes Surg 2015;25:818-23. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Enomoto TM, Larson D, Martindale RG. Patients requiring perioperative nutritional support. Med Clin North Am 2013;97:1181-200. ArticlePubMed

- 27. Ljungqvist O. ERAS--enhanced recovery after surgery:moving evidence-based perioperative care to practice. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2014;38:559-66. ArticlePubMed

- 28. Bear DE, Wandrag L, Merriweather JL, Connolly B, Hart N, Grocott MPW. Enhanced Recovery After Critical Illness Programme Group (ERACIP) investigators. The role of nutritional support in the physical and functional recovery of critically ill patients:a narrative review. Crit Care 2017;21:226.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 29. Elhassan AO, Tran LB, Clarke RC, Singh S, Kaye AD. Total parenteral and enteral nutrition in the ICU:evolving concepts. Anesthesiol Clin 2017;35:181-90. ArticlePubMed

- 30. Tian F, Heighes PT, Allingstrup MJ, Doig GS. Early enteral nutrition provided within 24 hours of ICU admission:a meta- analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med 2018;46:1049-56. ArticlePubMed

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

Cite

Cite