Abstract

-

Purpose

The post-operative quality of life (QoL) is a significant concern for patients undergoing gastrectomy. Unlike subtotal gastrectomy, the detailed aspects of QoL involving the ability to perform everyday activities that reflect physical, psychological, and social well-being; and satisfaction with levels of functioning and control of the disease after total gastrectomy remain poorly investigated.

-

Materials and Methods

We enrolled 170 patients who underwent total gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma and completed the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality-of-Life questionnaires (QLQ) C30 and STO22 preoperatively and post-operatively at 1, 6, and 12 months. We investigated the QoL change in terms of the minimally important difference (MID), which refers to a score change patients would perceive as clinically important (effect size >0.5).

-

Results

At 1-month post-surgery, MID in global health, physical, social, role, emotional, and cognitive functions was observed at 44.0%, 68.0%, 42.7%, 38.7%, 32.0%, and 16.0% respectively. Of QLQ-C30 symptoms, MID was frequently observed in appetite (52.9%). Of the QLQ-STO22 symptoms, MID was frequently observed in eating restrictions (74.1%), dysphagia (63.5%), pain (51.8%), and anxiety (50.6%). At 12 months post-surgery, MID in global health, physical, role, cognitive, social, and emotional functions was 32.9%, 58.8%, 42.4%, 40.0%, 36.5%, and 17.6%, respectively. Of QLQ-C30 symptoms, MID was frequently observed in diarrhea (52.9%). Of the QLQ-STO22 symptoms, MID was frequently observed in eating restrictions (63.5%), dysphagia (52.9%), body image (55.3%), pain (55.3%), and anxiety (51.8%). Male sex, comorbidity, D2 lymphadenectomy, and post-operative morbidity were associated with MID in global health at 12 months post-surgery.

-

Conclusion

This study provides information about the detailed aspects of impairment in various functions and symptoms of QoL after total gastrectomy. This information can be used to develop a tailor-made management plan for QoL.

-

Keywords: Stomach neoplasms; Quality of life; Gastrectomy

INTRODUCTION

Despite the decreasing global incidence, the incidence of proximal gastric cancer has gradually increased, particularly in the high-income countries [

1]. Although the prevalence of proximal gastric cancer is relatively low in the East Asia, approximately 20% of gastric cancer patients receive total gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer in South Korea [

2]. Patients suffer from various nutritional and functional deficits after gastrectomy, resulting in deterioration of the postoperative quality of life (QoL). Furthermore, patients undergoing total gastrectomy are more vulnerable to eating restrictions, nutritional deficits, and weight loss than patients undergoing subtotal gastrectomy [

3].

As survival of gastric cancer improves, there is an increasing interest in the management of QoL after gastrectomy. Nowadays, QoL has become one of the critical outcomes that should be factored into selecting a proper treatment plan. Several studies have demonstrated immediate deterioration in various functions and symptoms of QoL and gradual improvement in the first postoperative year after gastrectomy [

3-

8]. However, previous studies mostly focused on the patients undergoing subtotal gastrectomy, and detailed aspects of the functions and symptoms of QoL after total gastrectomy remain poorly investigated.

Many studies that analyzed the QoL after gastrectomy used a score-based comparison between the different groups or different time periods. However, this method has limited clinical value because it only shows the difference in scores without reflecting clinically meaningful QoL change [

9]. To make the QoL data more clinically relevant, many researchers have suggested the concept of minimally important difference (MID) in interpreting QoL [

10]. MID refers to a score change that patients would perceive as important, defined as an effect size of >0.5. MID is clinically useful to classify patients into those with and without deterioration of QoL and investigate the extent of impairment in various functions and symptoms of QoL. In this study, we investigated the longitudinal change of QoL after total gastrectomy using the MID-based approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study design and patients

This study was performed in a gastric cancer clinic at a tertiary teaching hospital in South Korea. Patients with gastric cancer aged 18 to 85 years who were expected to undergo total gastrectomy were eligible for this study. We excluded patients with other malignant diseases and those who received preoperative chemotherapy or underwent a non-curative gastrectomy. Between January 2016 and December 2017, 206 eligible patients were enrolled, and 170 patients provided a complete response to the QoL surveys from their initial preoperative visit and at the postoperative follow-up visits (months 1, 6, and 12). This study included these 170 patients to investigate the longitudinal change in QoL after total gastrectomy.

All patients underwent open or laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Laparoscopic surgery was indicated for clinically T1-2N0 tumors on the preoperative staging. D1+ or D2 lymphadenectomy was performed as appropriate based on the gastric cancer treatment guidelines [

11,

12]. After gastric resection, Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy was performed in all patients. Postoperatively, patients with stage II or higher cancer received adjuvant chemotherapy with oral fluoropyrimidine (TS-1) or capecitabine plus oxaliplatin.

Patients were routinely followed-up postoperatively at 1, 6, and 12 months in the first postoperative year. Thereafter, patients were regularly followed-up every 6 months until 5 years after surgery. During the follow-up, patients received an abdominal CT scan every 6 months and endoscopy every 12 months. The institutional review board at our institution (Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital, South Korea) approved this study (IRB No.: CNUHH-2020-268), which waived the requirement of informed consent of patients, considering that this study was an observational study without interventions.

2. Data collection

We prospectively collected clinicopathological outcomes and QoL data of patients. We collected demographic data (age, sex, body mass index, comorbidities, medical history, American Society of Anesthesiologists physiologic status, etc.), operative outcomes (operative approach, lymphadenectomy, operating time, operative blood loss, etc.), pathological results (histological type, differentiation, tumor size, location, and tumor, nodes, metastases [TNM] stage), and postoperative outcomes (diet initiation time, hospital stay, and postoperative complications). Postoperative morbidity was defined as any complications that occurred within 30 days after surgery. The severity of complications was graded based on the Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications [

13]. The pathologic stage followed the seventh edition of the International Union Against Cancer TNM classification of gastric carcinoma [

14].

The validated Korean version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core (QLQ-C30) [

15] and gastric cancer-specific module (STO22) gastric module [

16] were used to measure QoL. Briefly, the EORTC QLQ-C30 comprises global health, five functional, and nine symptom scales/items. Higher scores in global health and functional scales indicate better functional status, whereas higher symptom scores indicate worse symptoms. The STO22 gastric module examines the specific symptoms in gastric cancer patients and contains 22 questions for nine symptoms: dysphagia, pain, eating difficulties, anxiety, dry mouth, taste, body image, and hair loss. Higher scores in the STO22 module indicate worse symptoms.

Patients were asked to fill out the QoL questionnaires preoperatively and at postoperative 1, 6, and 12 months. The questionnaire responses were self-reported by patients, although a specialist nurse assisted patients who had difficulty reading or completing the questionnaire.

4. Quality of life interpretation

Scores in each subscale and symptom were linearly transformed to a 0 to 100 score following the EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO22 scoring manual [

17,

18]. Missing values were handled in accordance with the standard protocol described in the EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual [

17]. Briefly, missing items were assumed to have values equal to the average of those present for that respondent for multi-item scales. For single-item measures, the patient’s previous responses to the same item were used for imputation.

MID refers to a score change that patients would perceive as clinically important. We determined the MID for each subscale and symptom of the QLC-C30 and STO22 based on the standard deviation of the baseline score. An effect size (score change/standard deviation) of >0.5 was regarded as MID for each subscale [

19]. Using the MID, we investigated the proportions of patients who experienced score changes greater than the MID at each time point.

We also investigated the factors associated with the QoL recovery. The global health status can serve as a single representative domain that reflects the overall QoL. Therefore, we analyzed the association between various clinicopathological factors and MID in global health at postoperative 12 months. We selected nine possible factors (age, sex, body mass index, comorbidity, operative approach, the extent of lymphadenectomy, tumor stage, postoperative complication, and adjuvant chemotherapy) with reference to the researchers’ opinion and previous reports.

5. Statistical methods

The pairwise comparison of the scores at different time points was performed using a paired t-test. The proportions of patients with MID at different time points were compared using McNemar’s test. The logistic regression model was used for univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with global health recovery. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA); two-sided P-value<0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

1. Patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the clinicopathological characteristics of patients. The mean age was 62.7±11.6 years, and the mean body mass index was 23.7±3.3 kg/m

2. Operative outcomes showed that open and laparoscopic surgeries were performed in 46 and 124 patients, respectively. Sixty-three (27.1%) patients underwent D2 lymphadenectomy, and combined organ resection was performed in 14 (8.2%) patients. Postoperatively, 43 (25.3%) patients developed postoperative morbidity. The final pathologic results showed 114 (67.1%) in stage I, 27 (15.9%) in stage II, 25 (14.7%) in stage III, and four (2.4%) patients in stage IV. After surgery, 56 (32.9%) patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

2. Quality of Life Questionnaire Core (QLQ-C30)

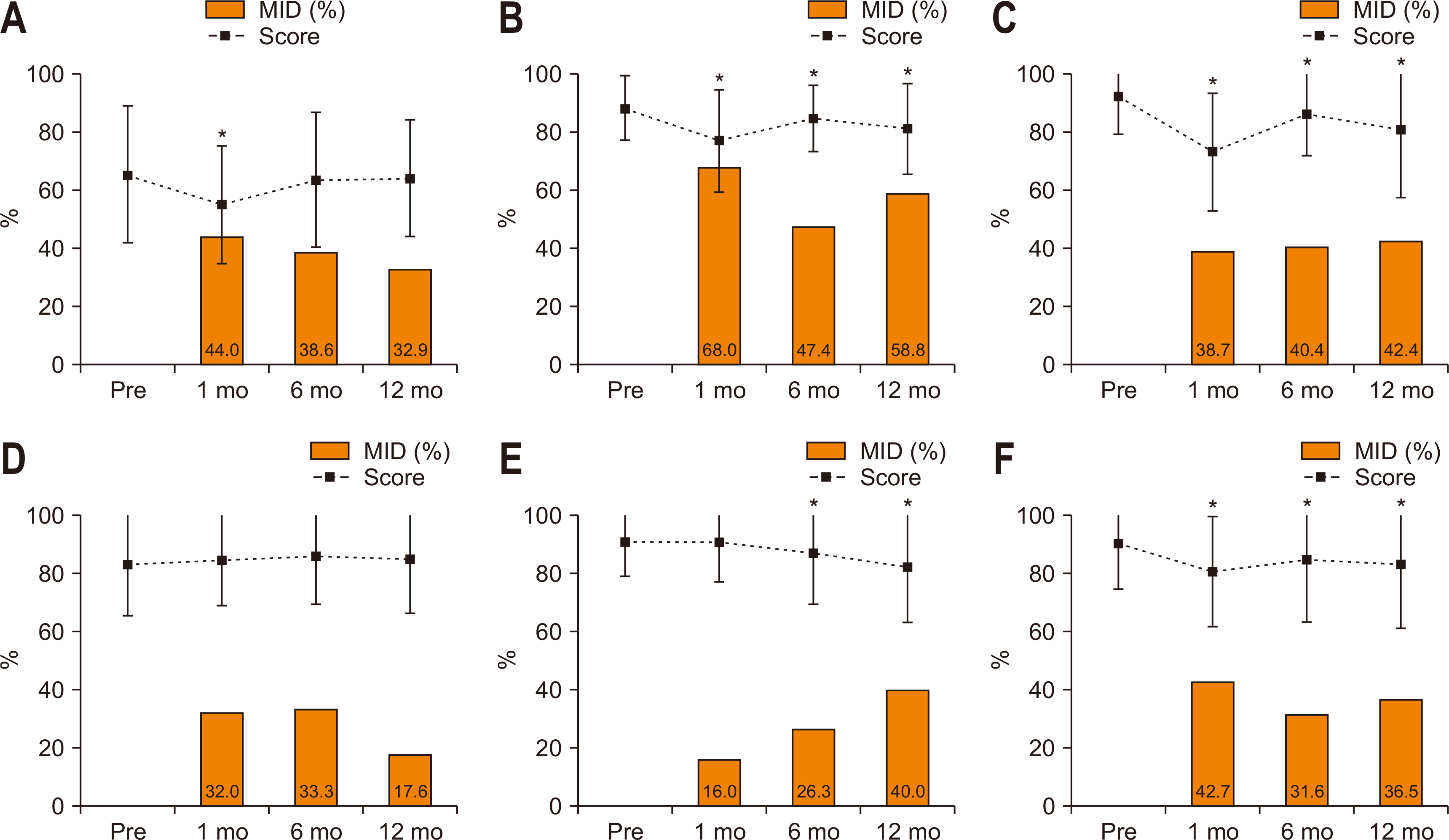

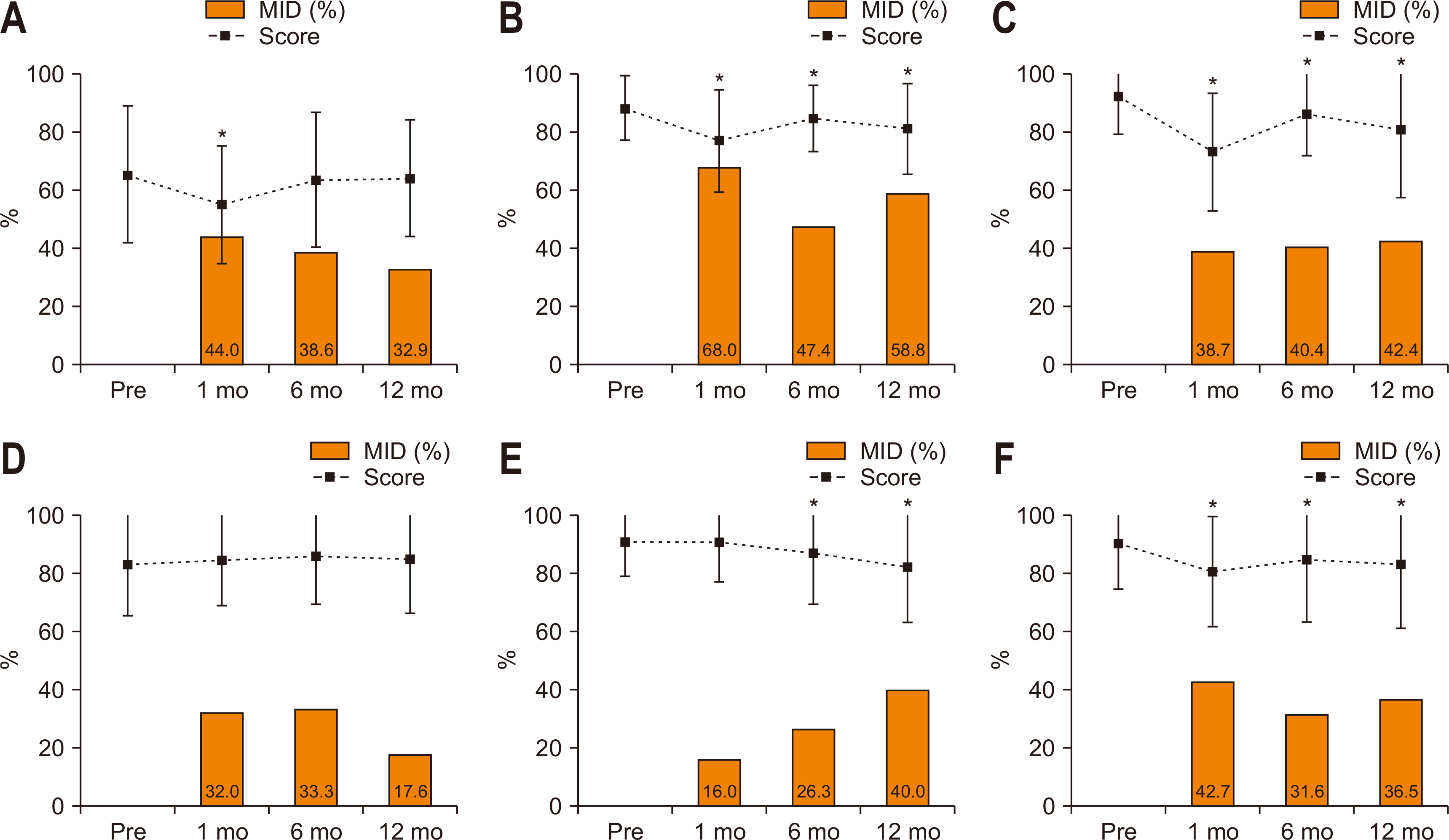

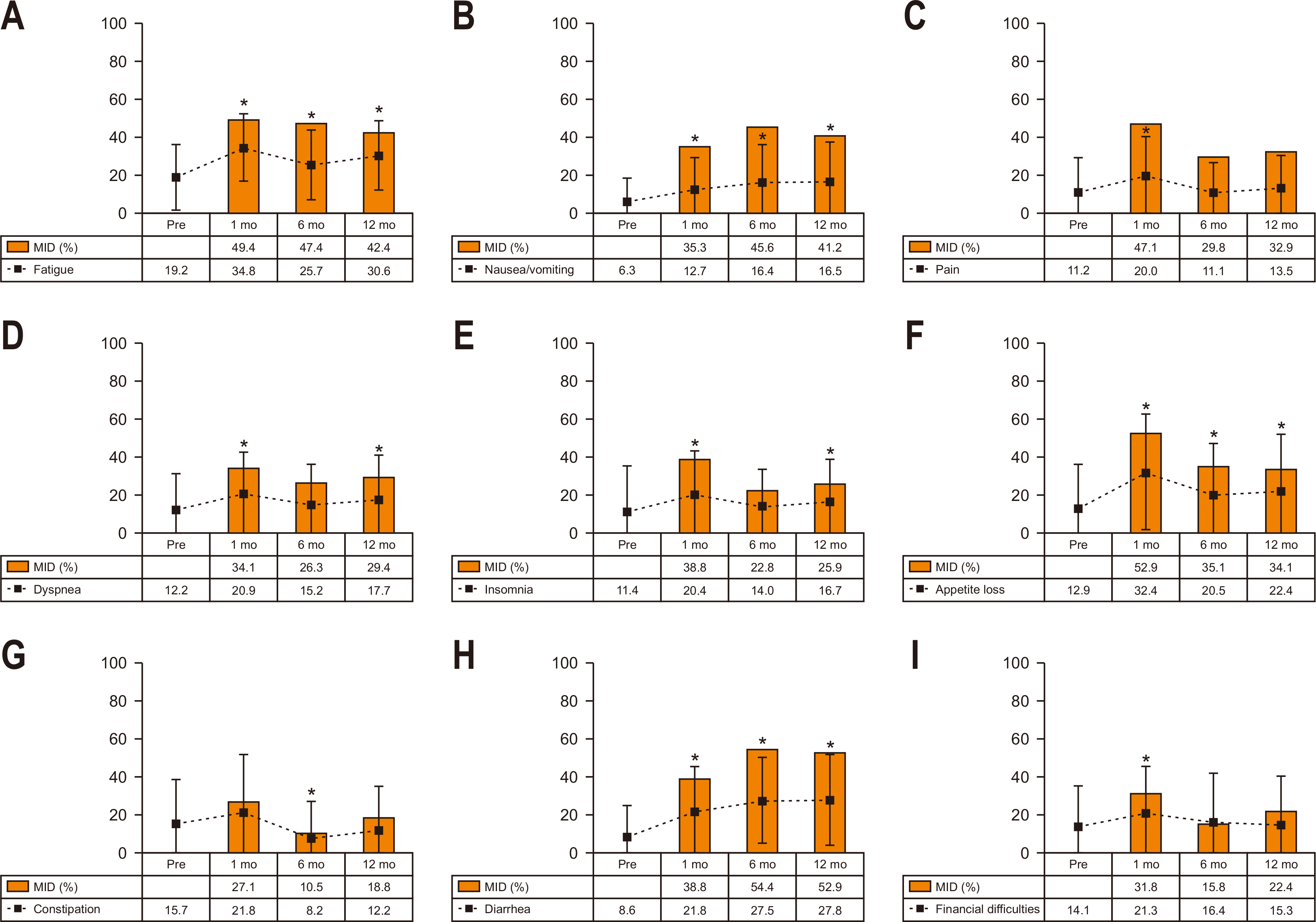

Fig. 1 shows the longitudinal change in scores and proportions having MID in global health status and five functions. At postoperative 1 month, the scores of global health, physical, role, and social functions significantly decreased (worsened) compared to the preoperative level. Meanwhile, the emotional and cognitive functions did not significantly change. Of patients, 44.0% showed MID in global health, 68.0% in physical function, 42.7% in social function, 38.7% in role function, 32.0% in emotional function, and 16.0% in cognitive function at postoperative 1 month. At postoperative 12 months, the global health score recovered to the preoperative level, but most functions (except emotional function) remained significantly changed (worsened). Of patients, 32.9% showed MID in global health status, and MID was most frequently observed in physical function (58.8%), followed by role function (42.4%), cognitive function (40.0%), social function (36.5%), and emotional function (17.6%) at postoperative 12 months.

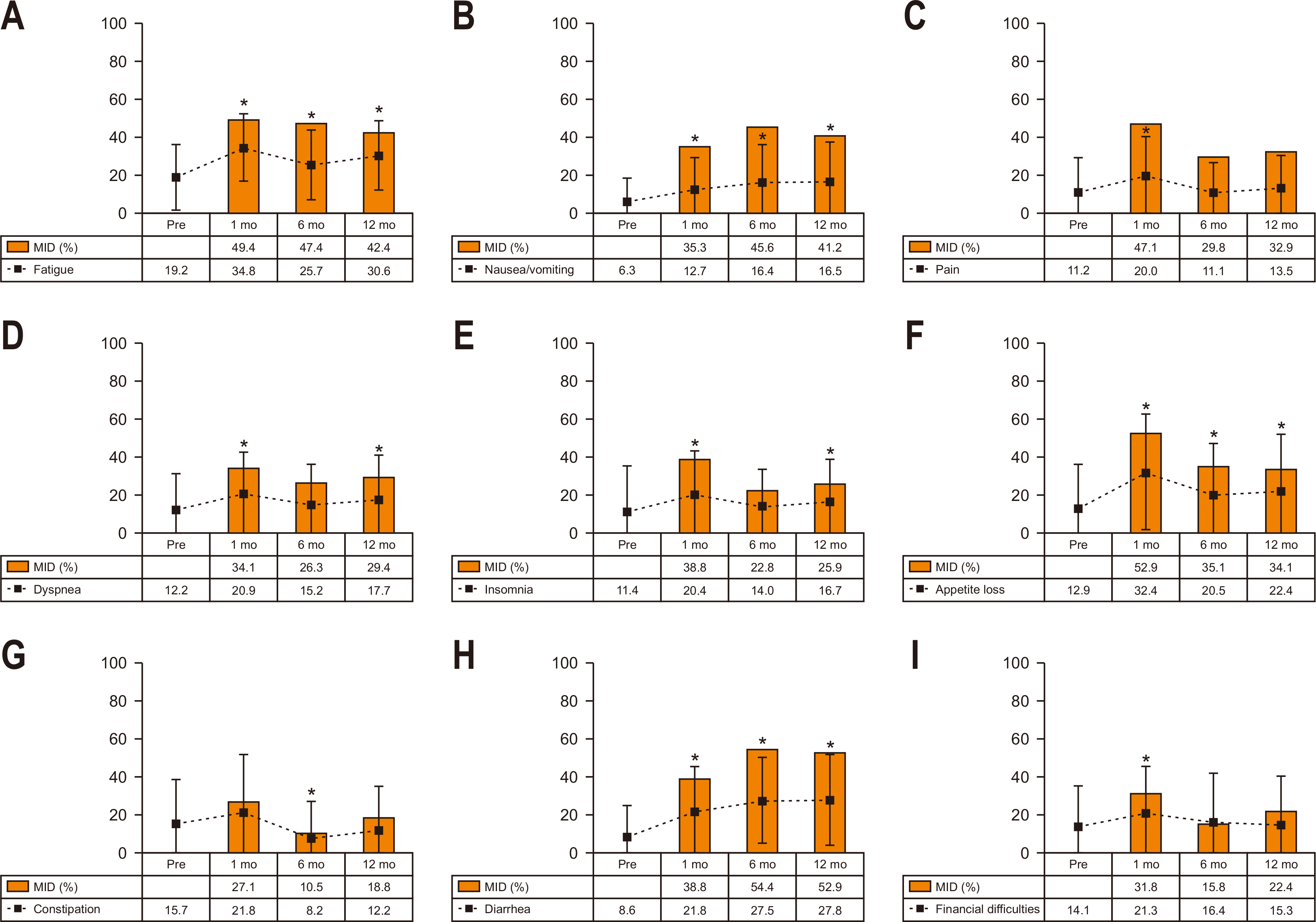

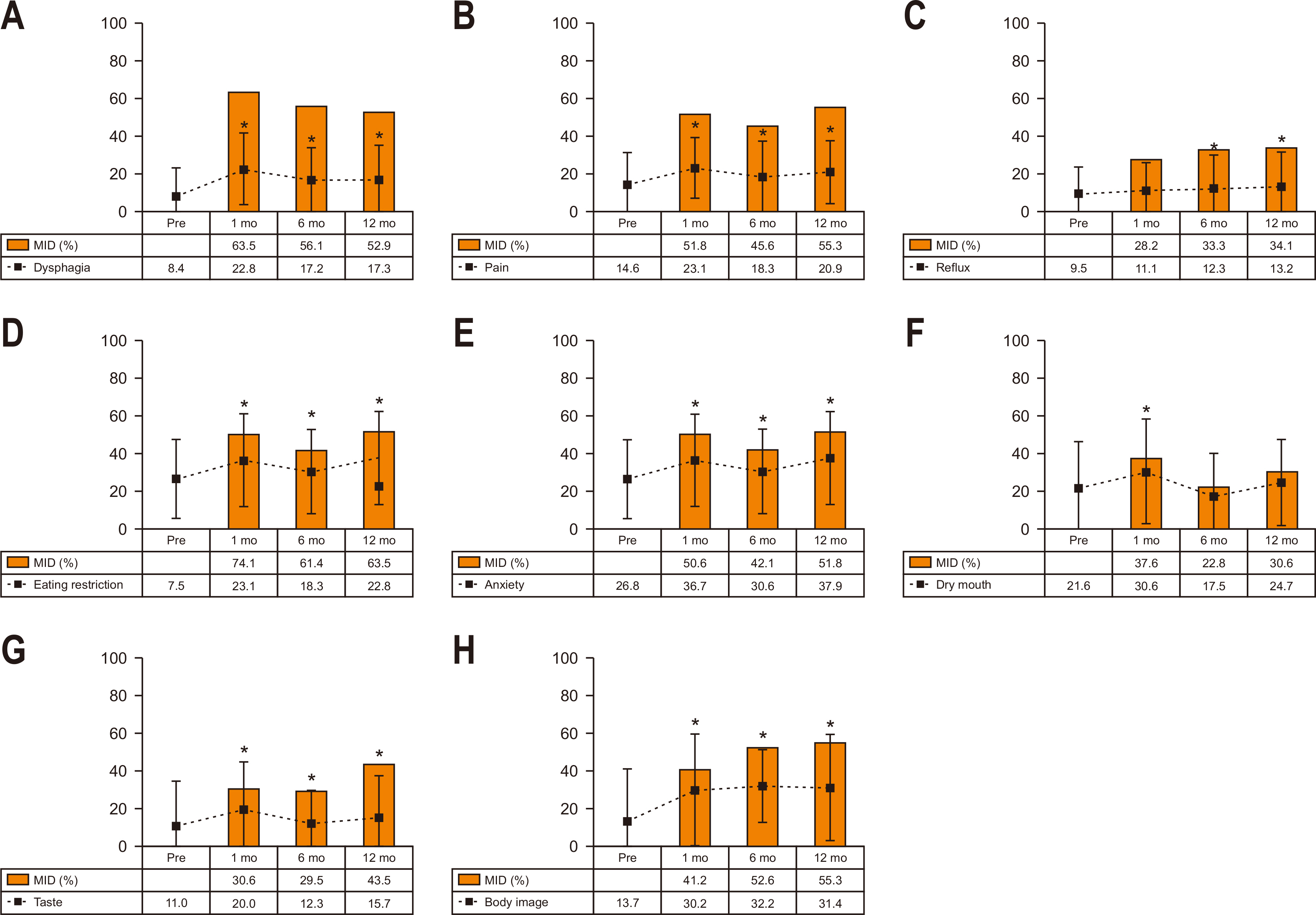

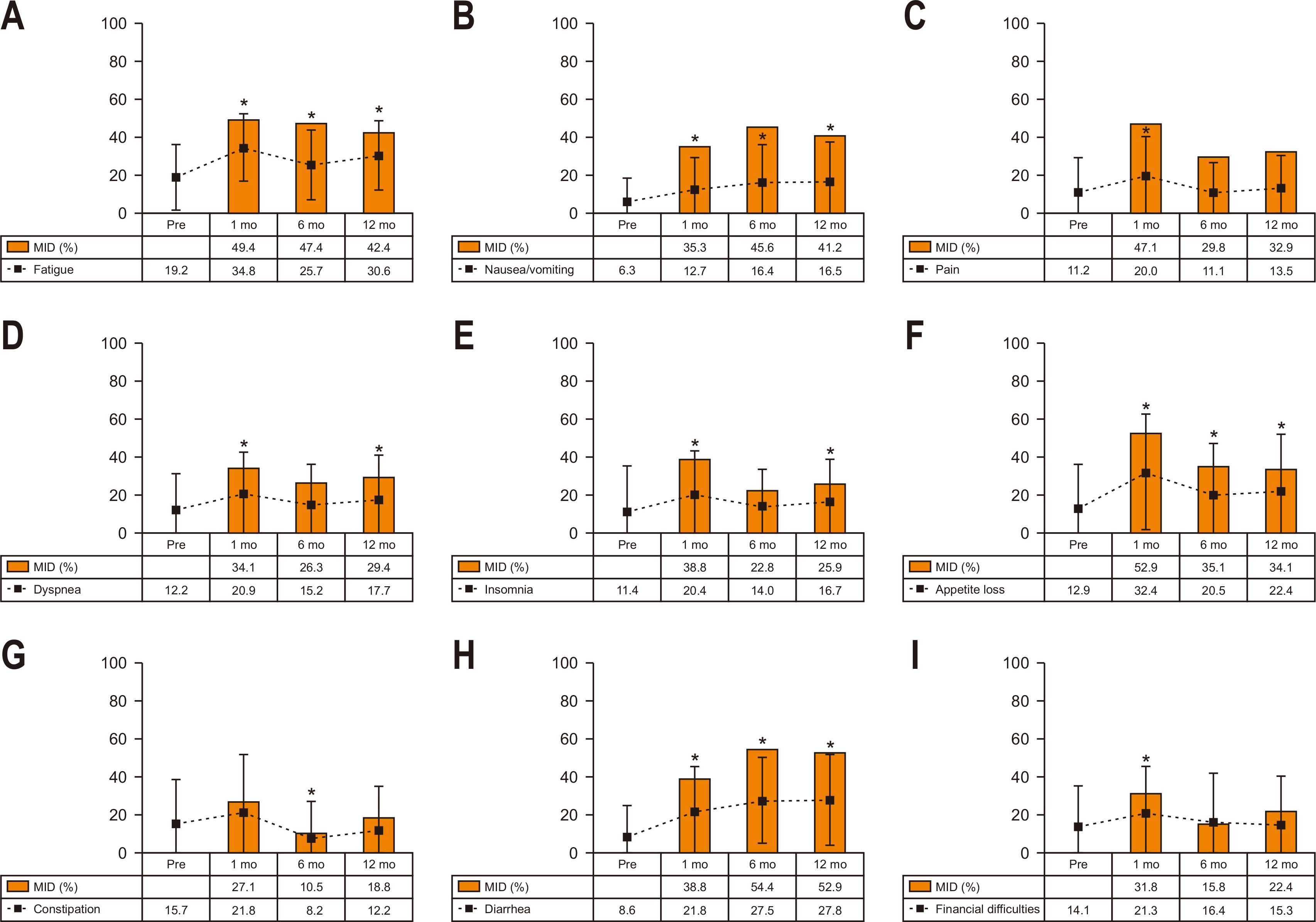

Fig. 2 shows the longitudinal change in scores and proportions having MID in QLQ-C30 symptoms. At postoperative 1 month, the scores of most symptoms (except for constipation) significantly increased (worsened) compared to the preoperative level. MID was most frequently observed in appetite loss (52.9%), followed by fatigue (49.4%), pain (47.1%), insomnia (38.8%), and diarrhea (38.8%). At postoperative 12 months, most symptoms remained significantly changed except for pain, constipation, and financial difficulties. MID was most frequently observed in diarrhea (52.9%), followed by fatigue (42.4%), nausea/vomiting (41.2%), appetite loss (34.1%), and pain (32.9%) at postoperative 12 months.

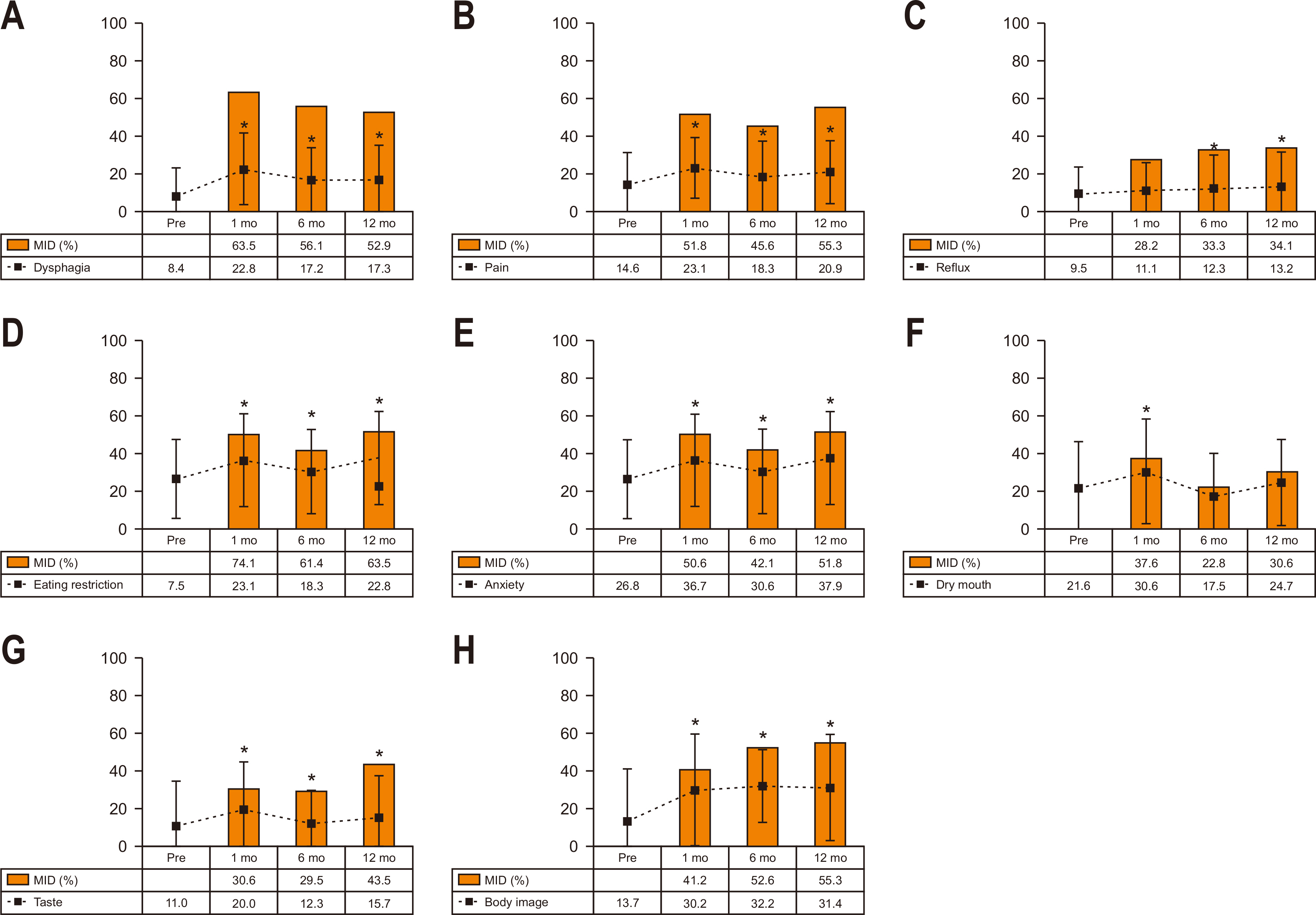

3. Gastric cancer-specific module (STO22)

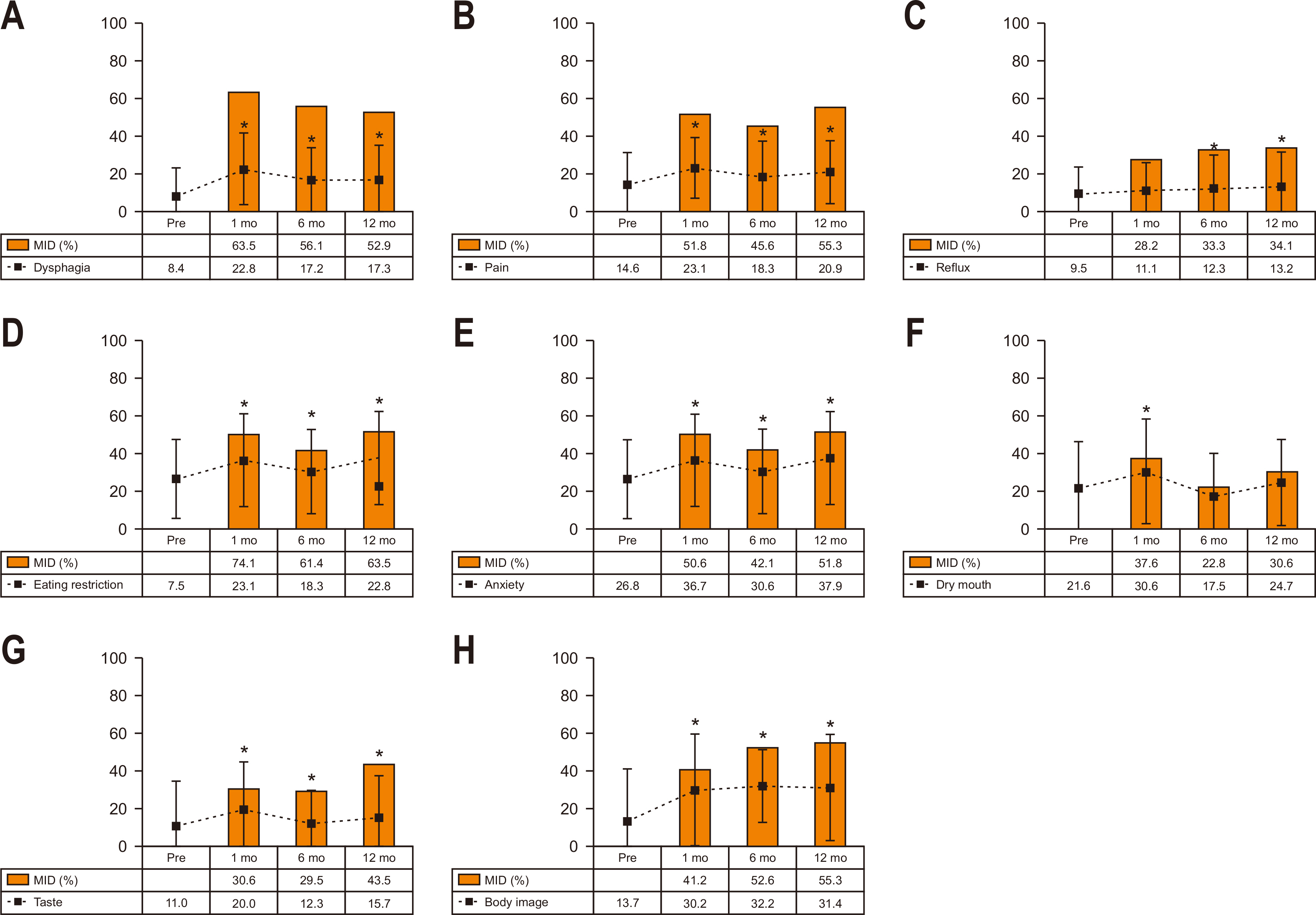

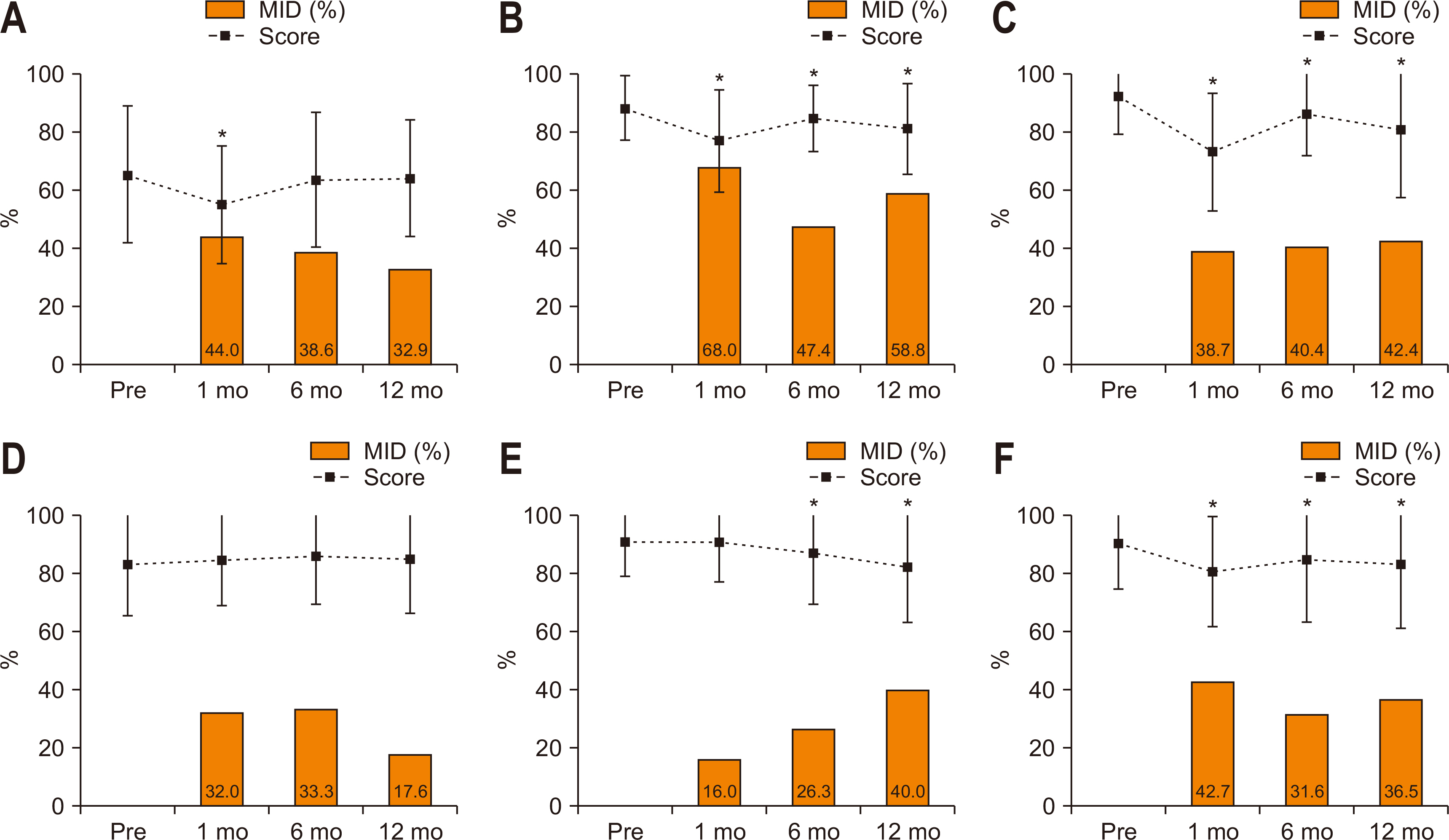

Fig. 3 shows the longitudinal change in scores and proportions having MID in STO22 symptoms. Hair loss was excluded from this analysis because of the low response rate. At postoperative 1 month, most symptoms (except for reflux) showed a significant increase (worsening) compared to the preoperative level. MID was most frequently observed in eating restrictions (74.1%), followed by dysphagia (63.5%), pain (51.8%), anxiety (50.6%), and body image (41.2%) at postoperative one month. At postoperative 12 month, most symptoms remained significantly increased except for dry mouth. MID was most frequently observed in eating restriction (63.5%), followed by body image (55.3%), pain (55.3%), dysphagia (52.9%), and anxiety (51.8%) at postoperative 12 months.

4. Factors affecting the recovery of global health

At postoperative 12 months, 60 (32.9%) patients showed MID in global health status. Nine variables, including age, sex, body mass index, comorbidity, operative approach, the extent of lymphadenectomy, TNM stage (stage I versus II~IV), postoperative complication, and adjuvant chemotherapy, were assessed concerning the association with developing MID in global health at postoperative 12 months (

Table 2). In the univariate analysis, male sex, comorbidity, D2 lymphadenectomy, and postoperative complication were associated with MID in global health at postoperative 12 months. Multivariate analysis revealed that male sex (odds ratio [OR]=6.25), comorbidity (OR=3.42), D2 lymphadenectomy (OR=4.68), and postoperative complication (OR=4.21) were independent predicting factor for MID in global health at postoperative 12 months.

DISCUSSION

QoL is a major concern for patients undergoing gastrectomy. Unlike subtotal gastrectomy, detailed aspects of QoL after total gastrectomy remains poorly investigated. To our knowledge, this is the largest study that prospectively investigated the longitudinal change in QoL after total gastrectomy. The strength of this study is that we analyzed the sequential change in diverse functions and symptoms of QoL in terms of MID. Using the MID-based approach, we could delineate the extent of impairment in various symptoms and functions of QoL at different time points after total gastrectomy. We found that deterioration in many functions and most symptoms persisted until postoperative 1 year after total gastrectomy. We believe this information can be used to develop a tailored care plan for QoL management. Furthermore, patients can be informed about detailed aspects of QoL when being provided information about surgery.

In this study, we used a different approach to interpret QoL, the concept of MID [

9]. A common method to analyze QoL data was a score-based comparison between the different groups or different periods in previous studies. However, this information is usually unrealistic or less informative because the statistical difference of the mean scores does not necessarily indicate a clinically relevant difference in QoL. Instead, many researchers have suggested using MID in reporting QoL data to provide more practical information [

9]. MID is defined as the smallest change of the QoL score (effect size of >0.5) that patients would perceive as clinically important [

10]. MID enables clinicians to identify patients who experienced a clinically relevant change in QoL.

Using the MID-based approach, we can understand detailed aspects of QoL after total gastrectomy. For instance, our study showed that of diverse functions, physical function was most severely affected throughout the postoperative period. The cognitive function worsened as time passed, while other functions remained unchanged or only mildly improved. Regarding the symptoms, we found that eating restriction, dysphagia, appetite loss, pain, and anxiety are relatively frequent symptoms that patients experienced MID (all>50%) at postoperative 1 month. At postoperative 12 months, MID was frequent (>50%) in eating restriction, body image, pain, diarrhea, dysphagia, and anxiety. Thus, we can understand which functions and symptoms of QoL are mostly affected at different postoperative periods. Based on this information, we can develop an appropriate care plan for QoL focusing on the main problems of patients.

Contrary to gradual improvement in other functional scales, we found that cognitive function worsened as time passed. The cognitive function did not show significant change immediately after surgery but began to show significant deterioration on postoperative 6 and 12 months. This interesting finding is also observed in other studies about QoL after gastrectomy [

4,

5,

7]. The exact cause of this is unclear. However, we can postulate that most patients are elderly, with a mean age of 63 years, and thus cognitive function declined as they grew older regardless of postoperative recovery. Furthermore, impaired nutrition status after gastrectomy may have influenced their cognitive function to some extent.

QoL after subtotal gastrectomy has been well investigated in several studies [

3-

8]. Many studies reported significant deterioration of QoL immediately after surgery and gradual improvement within the first postoperative year [

8]. Patients usually experienced deterioration in global health, physical, social, and role functions, while emotional and cognitive functions were relatively less affected [

4,

5]. Fatigue, nausea/vomiting, dysphagia, pain, appetite, and eating restriction were frequent symptoms that patients experienced deterioration [

4-

6].

Unlike subtotal gastrectomy, only a few studies investigated the QoL, focusing on the patients undergoing total gastrectomy [

20,

21]. Kim et al. [

4] compared the QoL between total and subtotal gastrectomy until postoperative 1 year. Patients undergoing total gastrectomy showed significantly worse scores in physical, role, and social functions, and many symptoms, including fatigue, dysphagia, pain, and eating restriction, compared to subtotal gastrectomy. The recovery of QoL was also slower after total gastrectomy. Lee et al. [

3] also compared the QoL after subtotal and total gastrectomy, particularly in long-term survivors with more than five years. They found that total gastrectomy resulted in significantly worse QoL in social function, nausea/vomiting, eating restrictions, and taste five years after surgery. Similarly, Hu et al. [

5] also showed that total gastrectomy was associated with poor late recovery in several functions and symptoms of QoL compared to subtotal gastrectomy. We also found that recovery of QoL after total gastrectomy was somewhat different from that observed after subtotal gastrectomy in previous studies. Unlike recovering QoL within 1 year after subtotal gastrectomy, our study showed that impairment in most functions and symptoms of QoL persisted until postoperative 1 year after total gastrectomy. More studies will be required to validate our results. However, this finding may suggest that management of QoL needs to be tailored considering the different aspects of QoL according to the extent of gastric resection.

In previous reports, operative approach [

22], tumor stage [

5], postoperative complication [

23], or the type of gastrectomy [

4,

5] were the main factors that affected postoperative QoL. Some studies showed that old age was associated with poor QoL after a gastrectomy [

24,

25]. Based on this, we included these factors and other clinically relevant factors to construct the predictive model for QoL recovery. For this, we designated the global health status as a primary outcome because it can represent the overall status of the patient’s QoL. We found that male sex, comorbidity, D2 lymphadenectomy, and postoperative morbidity were the main factors that were associated with MID in global health at postoperative 12 months. Patients with these clinical conditions may require careful attention with regard to QoL. Besides, D2 lymphadenectomy should be carefully decided in selected patients, and the efforts to reduce postoperative morbidity will also be helpful to improve QoL after total gastrectomy.

Some researchers have suggested proximal gastrectomy as an alternative, particularly for early-stage gastric cancer, because of the poor QoL after total gastrectomy. Some studies demonstrated that proximal gastrectomy resulted in less weight loss, diarrhea, and dumping symptoms compared to total gastrectomy [

26,

27]. However, the superiority of QoL with proximal gastrectomy remains controversial because of little benefit regarding the postoperative QoL in other studies [

28]. Meanwhile, cognitive-behavioral therapy is a commonly used technique for the treatment of various psychiatric diseases. Recently, this technique has been increasingly used to improve QoL in cancer patients, especially in breast cancer [

29]. In our institution, we are developing a postoperative rehabilitation program that adopts cognitive behavioral therapy to help patients cope with various clinical problems related to gastrectomy. We expect to demonstrate the effects of this program on the patient’s QoL in the future study.

There are some limitations in this study. First, this study was performed in a single high-volume institution that had a well-organized gastric cancer clinic. This may limit the generalizability of our findings. However, this longitudinal study in a large cohort of patients will be informative to understand the general picture of QoL after total gastrectomy. Second, many patients had early gastric cancer, and only 32.9% received adjuvant chemotherapy. Therefore, different aspects of QoL in patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy may require further investigation. Lastly, the follow-up period was relatively short to determine the long-term QoL. Information about long-term QoL may be more helpful to guide the proper management of QoL.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study showed in detail the extent of impairment in various functions and symptoms of QoL at different periods using the MID-based approach. We can understand which functions and symptoms are mostly affected at different periods after total gastrectomy. We also found that the impairment of most functions and symptoms persisted until a year after total gastrectomy. This information can be used to guide a proper management plan for improving QoL in patients undergoing total gastrectomy. Lastly, patients need to be explicitly informed about possible QoL outcomes when deciding on a treatment plan.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: SCP, MRJ. Data curation: SCP, OJ, JHK, MRJ. Formal analysis: OJ, MRJ. Investigation: SCP, OJ, JHK, MRJ. Methodology: OJ, MRJ. Project administration: MRJ. Resources: SCP, OJ, JHK, MRJ. Visualization: SCP, MRJ. Writing – original draft: SCP. Writing – review & editing: SCP, OJ, JHK, MRJ.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Fig. 1

Longitudinal change in scores and the MID in global health and functions. The dotted lines indicate score change and the square boxes indicate the proportions with the MID. (A) Global health status. (B) Physical functioning. (C) Role functioning. (D) Emotional functioning. (E) Cognitive functioning. (F) Social functioning.

MID = minimally important differences.

*Denotes P<0.05 in score change compared to the preoperative level (paired t-test).

Fig. 2

Longitudinal change in scores and the MID in QLQ-C30 symptoms. The dotted lines indicate score change and the square boxes indicate the proportions with MID. (A) Fatigue. (B) Nausea and vomiting. (C) Pain. (D) Dyspnea. (E) Insomnia. (F) Appetite loss. (G) Constipation. (H) Diarrhea. (I) Financial difficulties.

MID = minimally important differences; QLQ-C30 = Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30.

*Denotes P<0.05 in score change compared to the preoperative level (paired t-test).

Fig. 3

Longitudinal change in scores and the MID in STO22. The dotted lines indicate score change and the square boxes indicate the proportions with the MID. (A) Dysphagia. (B) Pain. (C) Reflux. (D) Eating. (E) Anxiety. (F) Dry mouth. (G) Taste. (H) Body image.

MID, minimally important differences; STO22 = gastric cancer-specific module.

*Denotes P<0.05 in score change compared to the preoperative level (paired t-test).

Table 1

|

Variable |

Patients (n=170) |

|

Age (yr) |

62.7±11.6 |

|

Sex |

|

|

Male |

136 (80.0) |

|

Female |

34 (20.0) |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

23.7±3.3 |

|

Comorbidity |

97 (57.1) |

|

ASA physiologic status |

|

|

1 |

41 (24.1) |

|

2 |

120 (70.6) |

|

3 |

9 (5.3) |

|

Operative approach |

|

|

Laparoscopy |

124 (72.9) |

|

Open |

46 (27.1) |

|

Lymphadenectomy |

|

|

D1+ |

107 (62.9) |

|

D2 |

63 (37.1) |

|

Combined organ resection |

14 (8.2) |

|

Gall bladder |

8 |

|

Spleen |

4 |

|

Small bowel |

2 |

|

Operating time (min) |

284.6±87.1 |

|

Operative blood loss (mL) |

106.1±111.2 |

|

Postoperative morbidity |

43 (25.3) |

|

≥Grade 3a

|

12 (7.1) |

|

Postoperative hospital stay (days) |

10.3±7.8 |

|

TNM stageb

|

|

|

I |

114 (67.1) |

|

II |

27 (15.9) |

|

III |

25 (14.7) |

|

IV |

4 (2.4) |

|

Adjuvant chemotherapy |

56 (32.9) |

|

TS-1 |

40 |

|

Oxaliplatin+capecitabine |

16 |

Table 2Factors associated with MID in global health at postoperative 12 months

|

Variables |

OR |

95% CI |

P |

|

Univariate analysis |

|

|

|

|

Age (yr) |

1.02 |

0.98~1.06 |

0.267 |

|

Sex (male) |

5.15 |

1.66~15.93 |

0.004 |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

0.95 |

0.83~1.08 |

0.401 |

|

Comorbidity |

3.59 |

1.55~8.35 |

0.003 |

|

Operative approach (laparoscopy) |

2.09 |

0.76~5.73 |

0.152 |

|

D2 Lymphadenectomy |

2.87 |

1.27~9.25 |

0.015 |

|

TNM stage (II~IV) |

1.81 |

0.49~6.66 |

0.367 |

|

Postoperative complication |

4.99 |

1.76~14.17 |

0.002 |

|

Adjuvant chemotherapy |

1.41 |

0.38~5.16 |

0.605 |

|

Multivariate analysis |

|

|

|

|

Sex (male) |

6.25 |

2.10~18.61 |

0.001 |

|

Comorbidity |

3.42 |

1.55~7.55 |

0.002 |

|

D2 Lymphadenectomy |

4.68 |

1.96~11.18 |

0.001 |

|

Postoperative complication |

4.21 |

1.56~11.39 |

0.005 |

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 2. Information Committee of Korean Gastric Cancer Association. Korean Gastric Cancer Association nationwide survey on gastric cancer in 2014. J Gastric Cancer 2016;16:131-40. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 3. Lee SS, Chung HY, Kwon OK, Yu W. Long-term quality of life after distal subtotal and total gastrectomy: symptom- and behavior-oriented consequences. Ann Surg 2016;263:738-44. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Kim AR, Cho J, Hsu YJ, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, et al. Changes of quality of life in gastric cancer patients after curative resection: a longitudinal cohort study in Korea. Ann Surg 2012;256:1008-13. ArticlePubMed

- 5. Hu Y, Vos EL, Baser RE, Schattner MA, Nishimura M, Coit DG, et al. Longitudinal analysis of quality-of-life recovery after gastrectomy for cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:48-56. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 6. Karanicolas PJ, Graham D, Gönen M, Strong VE, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Quality of life after gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg 2013;257:1039-46. ArticlePubMed

- 7. Kobayashi D, Kodera Y, Fujiwara M, Koike M, Nakayama G, Nakao A. Assessment of quality of life after gastrectomy using EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO22. World J Surg 2011;35:357-64. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 8. Shan B, Shan L, Morris D, Golani S, Saxena A. Systematic review on quality of life outcomes after gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol 2015;6:544-60. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. King MT, Fayers PM. Making quality-of-life results more meaningful for clinicians. Lancet 2008;371:709-10. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 2003;41:582-92. ArticlePubMed

- 11. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer 2017;20:1-19. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Guideline Committee of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association (KGCA), Development Working Group & Review Panel. Korean practice guideline for gastric cancer 2018: an evidence-based, multi-disciplinary approach. J Gastric Cancer 2019;19:1-48. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 13. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-13. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. In: Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C, editors. 2010. TNM classification of malignant tumors. 7th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; Chichester.Article

- 15. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365-76. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Vickery CW, Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Arraras J, Sezer O, Koller M, et al. EORTC Quality of Life Group. Development of an EORTC disease-specific quality of life module for use in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 2001;37:966-71. ArticlePubMed

- 17. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). 2001. EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. EORTC; Brussels.Article

- 18. Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Bottomley A, Vickery C, Arraras J, Sezer O, et al. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gastrointestinal and Quality of Life Groups. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-STO 22, to assess quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:2260-8. ArticlePubMed

- 19. Sullivan GM, Feinn R. Using effect size-or why the p value is not enough. J Grad Med Educ 2012;4:279-82. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 20. Tanaka C, Kanda M, Murotani K, Yoshikawa T, Cho H, Ito Y, et al. Long-term quality of life and nutrition status of the aboral pouch reconstruction after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a prospective multicenter observational study (CCOG1505). Gastric Cancer 2019;22:607-16. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 21. Tyrväinen T, Sand J, Sintonen H, Nordback I. Quality of life in the long-term survivors after total gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2008;97:121-4. ArticlePubMed

- 22. Yasuda K, Shiraishi N, Etoh T, Shiromizu A, Inomata M, Kitano S. Long-term quality of life after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 2007;21:2150-3. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 23. Derogar M, Orsini N, Sadr-Azodi O, Lagergren P. Influence of major postoperative complications on health-related quality of life among long-term survivors of esophageal cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1615-9. ArticlePubMed

- 24. Jakstaite G, Samalavicius NE, Smailyte G, Lunevicius R. The quality of life after a total gastrectomy with extended lymphadenectomy and omega type oesophagojejunostomy for gastric adenocarcinoma without distant metastases. BMC Surg 2012;12:11.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 25. Díaz De Liaño A, Oteiza Martínez F, Ciga MA, Aizcorbe M, Cobo F, Trujillo R. Impact of surgical procedure for gastric cancer on quality of life. Br J Surg 2003;90:91-4. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Takiguchi N, Takahashi M, Ikeda M, Inagawa S, Ueda S, Nobuoka T, et al. Long-term quality-of-life comparison of total gastrectomy and proximal gastrectomy by postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS-45): a nationwide multi-institutional study. Gastric Cancer 2015;18:407-16. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 27. Nishigori T, Okabe H, Tsunoda S, Shinohara H, Obama K, Hosogi H, et al. Superiority of laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with hand-sewn esophagogastrostomy over total gastrectomy in improving postoperative body weight loss and quality of life. Surg Endosc 2017;31:3664-72. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 28. Park JY, Park KB, Kwon OK, Yu W. Comparison of laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with double-tract reconstruction and laparoscopic total gastrectomy in terms of nutritional status or quality of life in early gastric cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018;44:1963-70. ArticlePubMed

- 29. Getu MA, Chen C, Panpan W, Mboineki JF, Dhakal K, Du R. The effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on the quality of life of breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Qual Life Res 2021;30:367-84. ArticlePubMedPDF

, Oh Jeong, M.D., Ph.D.

, Oh Jeong, M.D., Ph.D. , Ji Hoon Kang, M.D.

, Ji Hoon Kang, M.D. , Mi Ran Jung, M.D., Ph.D.

, Mi Ran Jung, M.D., Ph.D.

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN Cite

Cite