Indexed in:

Scopus, KCI, KoreaMed

Scopus, KCI, KoreaMed

Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Clin Nutr Metab > Volume 14(2); 2022 > Article

- Review Article Selection of the Enterostomy Feeding Route in Enteral Nutrition

-

Dong-Seok Han, M.D., M.S.

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15747/ACNM.2022.14.2.50

Published online: December 1, 2022

Department of Surgery, SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- Corresponding author: Dong-Seok Han E-mail handongseok@gmail.com ORCID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9003-7987

• Received: May 30, 2022 • Revised: October 19, 2022 • Accepted: October 25, 2022

© The Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition and The Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 6,568 Views

- 44 Download

- 1 Crossref

Abstract

- Enteral nutrition has several physiologic advantages. For example, it can reduce complications, result in immunological improvement, and prevent bacterial translocation by maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier. Enteral tube feeding has a major role in nutritional support of patients with swallowing disorders caused by stroke or other neurologic disorders, neoplasms of the upper digestive tract, and benign esophageal stricture. This review article aimed to present the current knowledge on the clinical application of enteral tube feeding. Especially, based on a literature search on PubMed using the index terms of enteral tube feeding; the indications, advantages, and disadvantages; and insertion methods of various enteral tubes were identified.

INTRODUCTION

Enteral nutrition (EN) is not only more physiological than parenteral nutrition, but is also associated with better patient outcomes, decreased costs, and a lower incidence of septic complications [1,2]. Enteral tube feeding plays an important role in nutritional support among patients with a swallowing disorder caused by stroke or other neurologic disorders, neoplasms of the upper digestive tracks, and benign esophageal stricture [3-5]. In patients who cannot be fed via the oropharyngeal route, endoscopic-, radiologic-, or surgical-assisted methods must be used to provide EN.

For a short-term period, EN can be performed via nasogastric (NG) tube feeding. However, if enteral tube feeding is required for the long-term, enterostomy tube feeding is recommended for several reasons [6]. First, long-term NG tube feeding causes various complications including tube displacement, aspiration, and trauma to the nasal cavity [7]. Second, feeding interruptions attributed to tube displacement can result in inadequate nutritional intake. Third, based on findings of several studies, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube feeding is both clinically and nutritionally better than NG tube feeding [8,9]. This review article aimed to present the current knowledge on the clinical application of enteral tube feeding. Based on a literature search on PubMed using the index terms of enteral tube feeding, the indications, advantages and disadvantages, and insertion methods of various enteral tubes were identified.

ENTEROSTOMY TUBE FEEDING

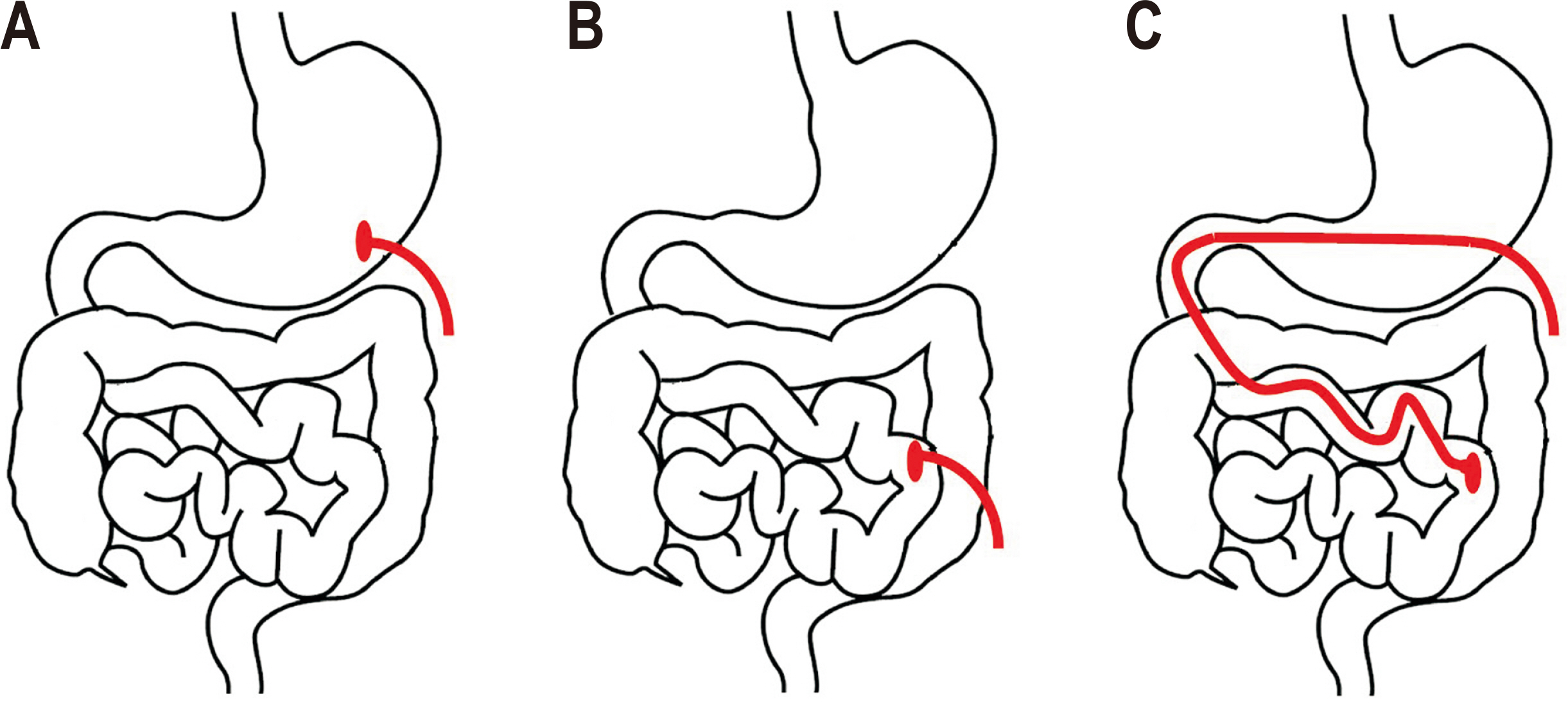

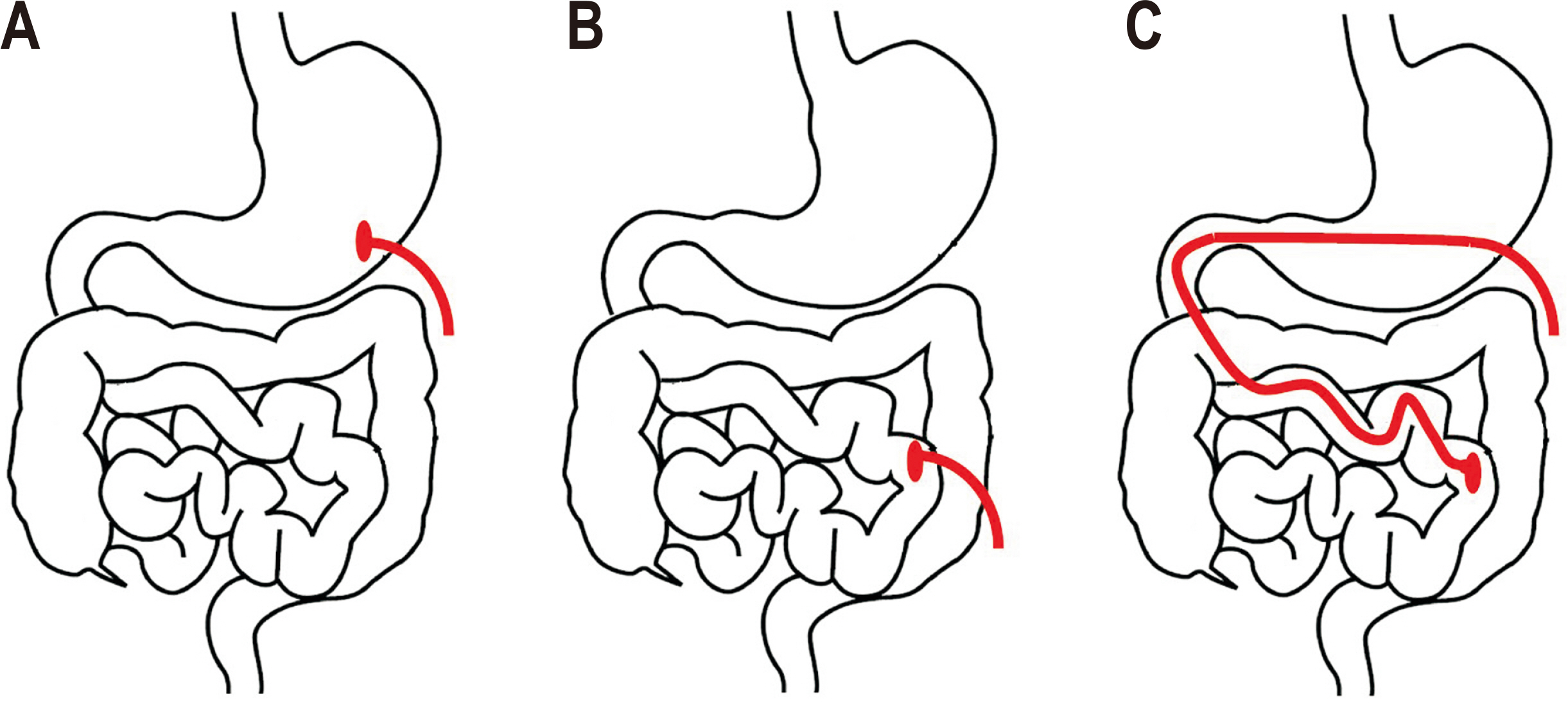

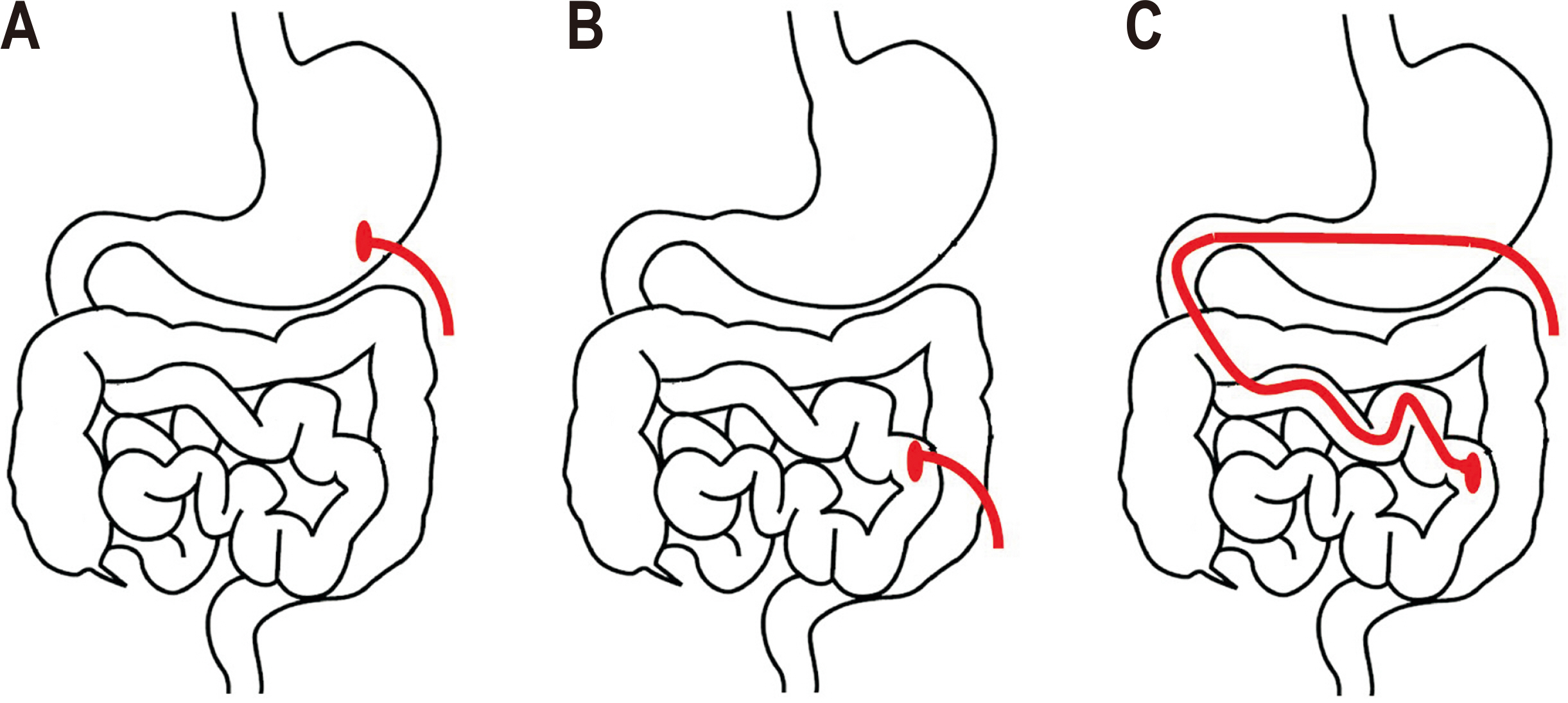

The disease state, gastrointestinal anatomy of patients, and accessibility should be considered when selecting the enteral feeding route [10]. Enteral access is generally required for patients who cannot consume or tolerate oral nutrition for an extended period. In patients requiring EN for >4 weeks, the enteral access routes include gastrostomy, jejunostomy, and gastrojejunostomy tubes (Fig. 1). Although these enterostomies have similar indications, certain conditions require a particular access [11]. The tubes are placed using three methods: (1) endoscopically by a gastroenterologist, (2) fluoroscopically by a radiologist, and (3) surgically (open or laparoscopic technique) by a surgeon using general anesthesia. The use of an enterostomy tube can be either temporary or permanent. If patients regain their ability to eat and no longer require tube feeding, the tube can be removed. The enterostomy opening commonly closes on its own.

INDICATIONS

Table 1 shows the indications for enterostomy tube feeding. In most cases, gastrostomy feeding is appropriate. Jejunostomy feeding is preferred for patients who cannot tolerate gastrostomy feeding because of gastroparesis. Jejunostomy is also preferred for those with pyloric obstruction or severe gastroesophageal reflux disease or in whom a gastrostomy tube cannot be inserted due to altered anatomical structures after procedures such as esophagectomy and gastrectomy. The risk of aspiration pneumonia in critically ill-patients is virtually the same for gastric and jejunal feeding according to one meta-analysis [12]. Also, in a recent randomized controlled trial on critically ill patients, the nasoduodenal feeding group had a superior outcome to the NG feeding group in mean daily calorie and protein intake; and nutritional goals were achieved earlier by better tolerance in the nasoduodenal feeding group [13]. Therefore, jejunal feeding can be an alternative in patients with intolerance of gastric feeding, severe gastroesophageal reflux disorder, or high risk of aspiration pneumonia.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

The absolute contraindications to enterostomy tube feeding include decreased function of the digestive tract caused by intestinal obstruction, compromised blood supply, peritonitis, and severe coagulation disorder (Table 2). Peptic ulcers in the stomach and duodenum with active bleeding and vessel engorgement are a relative contraindication to gastrostomy. Because of the risk of bleeding recurrence in those cases, gastrostomy insertion must be delayed for about 72 hours. Gastrostomy insertion is difficult in the presence of massive ascites and increases the risk of bacterial peritonitis in those cases [14]. After drainage of ascites by paracentesis, gastrostomy tubes can be inserted safely if the re-accumulation of ascites can be controlled for 7~10 days after gastrostomy insertion to allow tract maturation. In PEG or percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy (PRG), interposition of the liver or colon between the abdominal wall and the stomach, which commonly requires surgical gastrostomy, is another challenge.

GASTROSTOMY

In principle, the following techniques are used for insertion of PEG: the per-oral pull technique, per-oral push technique, and direct percutaneous procedure. The per-oral pull technique, which was introduced in 1980, is the most commonly used PEG insertion method [15]. Rather than surgical gastrostomy, PEG has been used as the mid- to long-term supply method for EN, as PEG is safer, more cost effective, and is associated with a lower in-procedure mortality rate (0.5%~2%) and morbidity rate [16,17]. There is less discontinuation of EN caused by tube displacement compared with the NG tube [18]. The success rate of PEG tube insertion is as high as 99.5% (range: 76%~100%). The causes of failure in PEG insertion involve inadequate transillumination via the abdominal wall, complete upper digestive tract obstruction, interposition of the liver or colon between the abdominal wall and the stomach, and gastrectomy. If EN via the PEG tube is unnecessary, the tube can be endoscopically extracted or the internal bumper can be passed internally after cutting. Some newly developed PEG tubes can be extracted by collapsing the internal balloon or by pulling the PEG via the opening in the abdominal wall [19].

PRG using the Seldinger technique was first introduced by Preshaw [20] in 1981. PRG is primarily indicated for dysphagia caused by curable upper gastrointestinal cancer because this method does not require endoscopy that could disseminate tumor cells [21]. PRG has undergone several modifications in gastropexy procedures, the process of fixing the stomach to the abdominal wall, and is a safe method with low complication rates. Triangle- or square-shaped anchoring devices are commonly used around the tract in gastropexy. Puncture of the stomach wall is performed in the center of the anchoring devices, similar to T-fasteners. Then a stiff wire is inserted, and the gastrostomy tract is created via either rigid or balloon dilation. The success rate of PRG is 98%~99%. The main causes of placement failure are similar to those of PEG. In the case of a stomach located in the thorax, transthoracic PRG insertion may be possible; however, jejunostomy should be considered [22].

Surgical gastrostomy by open procedure was first described by Stamm in 1894. This was the standard procedure for long-term EN until the early 1980s when PEG was introduced. Surgical gastrostomy can be considered in patients who cannot receive PEG or PRG or can be performed as an additional procedure during surgery. PEG should be avoided in patients with an inaccessible stomach because of oroesophageal tract obstruction, a previous history of upper abdominal issues including gastrectomy and PEG failure, interposition of the liver or colon between the abdominal wall and the stomach, and a high displacement of the stomach with hiatal hernia [23]. In such clinical conditions, surgical gastrostomy is the preferred procedure, and this surgery can be performed by open traditional technique or laparoscopic approach. The laparoscopic approach has a smaller incision size, decreased associated pain, better cosmetic outcome, and lower risk of incisional hernia. Moreover, compared with the open approach, the laparoscopic approach allows better visualization of the stomach and intra-abdominal cavity [24]. However, the laparoscopic approach may be difficult to apply in cases of severe adhesions and may cause challenges in stomach mobilization in patients with a previous history of upper abdominal surgery. This surgical approach should be selected based on clinical conditions such as a previous history of abdominal surgery, prognosis, obesity, and neurologic capacity of patients [25].

JEJUNOSTOMY

Jejunostomy is a useful surgery for short- and long-term enteral feeding when stomach feeding is contraindicated in patients. This occurs in patients who underwent esophageal or gastric surgery and in those with severe gastroesophageal reflux. Jejunostomy insertion can be performed using the percutaneous technique either endoscopically or radiologically or open via laparotomy or laparoscopy. Direct percutaneous jejunostomy can be placed by tube insertion into the first or second jejunal loop. This technique is similar to the per-oral pull technique used in gastrostomy. Based on the anatomical structure of the patient, different types of endoscopes (gastroscope, enteroscope, and colonoscope) can be used. Ideally, the second loop of the jejunum (20 cm after Treitz’s ligament) should be punctured. However, the location is practically determined via optical transillumination and finger indentation [26,27]. Three basic types of surgical jejunostomy are used: Witzel jejunostomy, Roux-en-Y jejunostomy, and needle catheter jejunostomy. Witzel jejunostomy involves the seromuscular suture for creating a serosal tunnel around the tube, and this is the preferred procedure by some surgeons. In needle catheter jejunostomy, a needle is inserted obliquely on the mesenteric side of the jejunum. The Seldinger technique is used for subsequent insertion of the feeding tube via the abdominal wall. The external end of the jejunostomy tube is removed via the anterior abdominal wall distant from the laparotomy incision [28]. Laparoscopic and radiologic jejunostomy tube insertions demonstrate high success rates (95% vs. 97%) and low morbidity rates (6% vs. 5%) [29].

GASTROJEJUNOSTOMY

Gastrojejunostomy involves placing the tube tip into the jejunum via a puncture made in the stomach wall under endoscopic or fluoroscopic guidance. This procedure can be conducted as an initial placement of feeding tube or can be performed via conversion of a prior gastrostomy to a gastrojejunostomy. If gastropexy was conducted during the prior gastrostomy, conversion to gastrojejunostomy can be performed at any time. If gastropexy was not performed, conversion to gastrojejunostomy can be performed after the tract matures (commonly within 1~3 weeks). If the patients have a history of gastroesophageal reflux or aspiration pneumonia, percutaneous radiologic gastrojejunostomy can be considered. However, whether gastrojejunostomy can decrease the incidence of gastroesophageal reflux or aspiration pneumonia is controversial [30,31]. Gastrojejunostomy tubes are longer and narrower than gastrostomy tubes placed in the stomach; and the use of these tubes can increase the incidence of complications, such as tube obstruction [32].

CONCLUSION

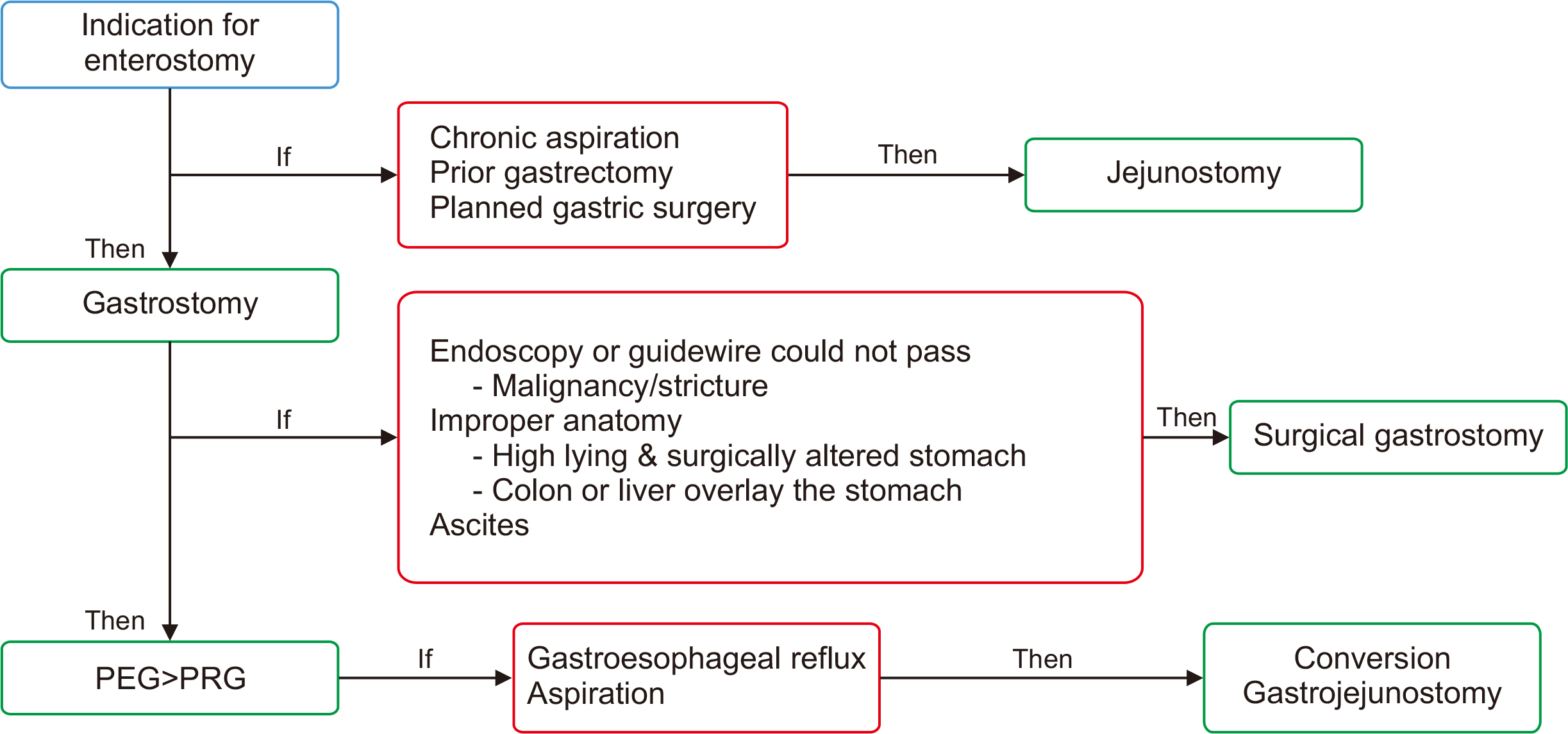

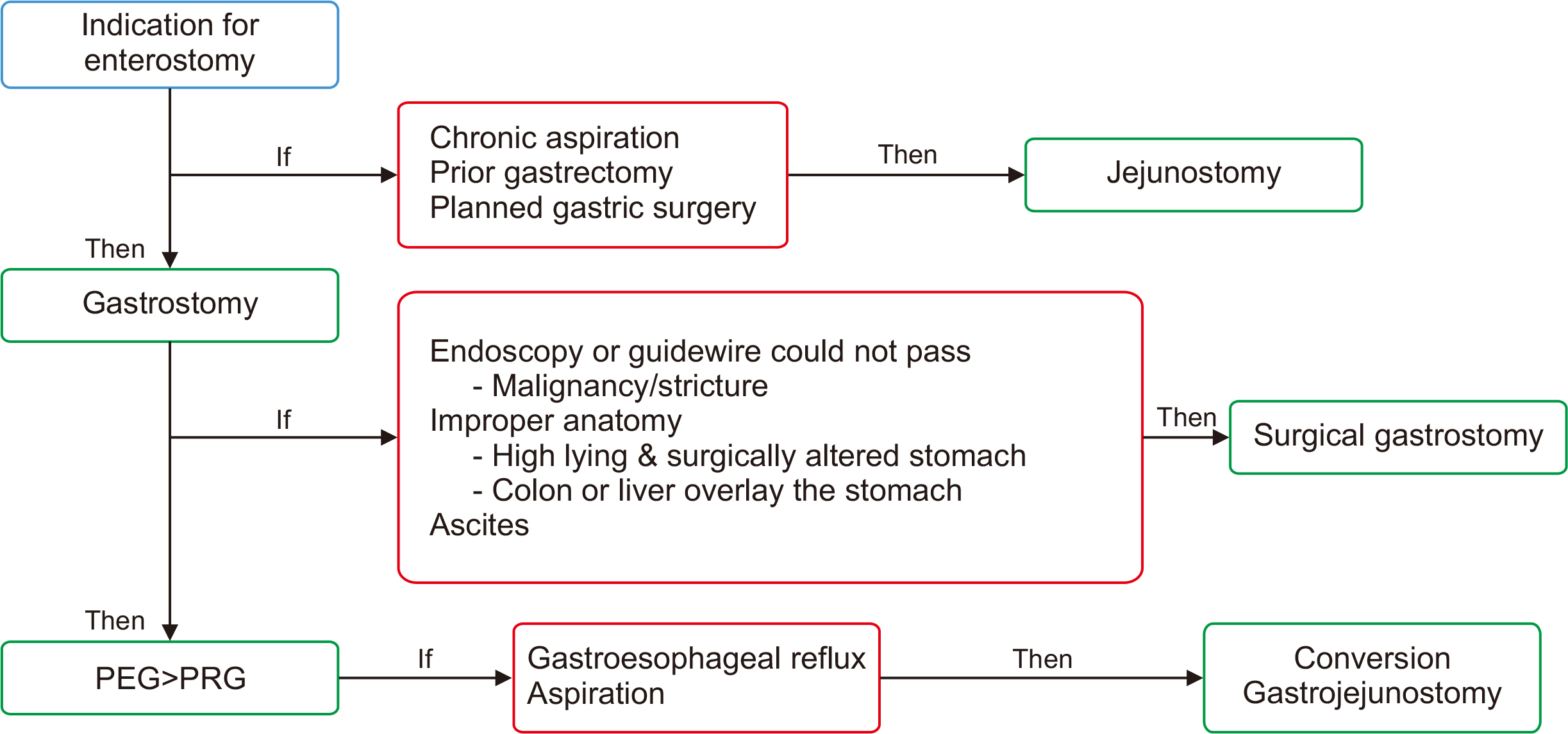

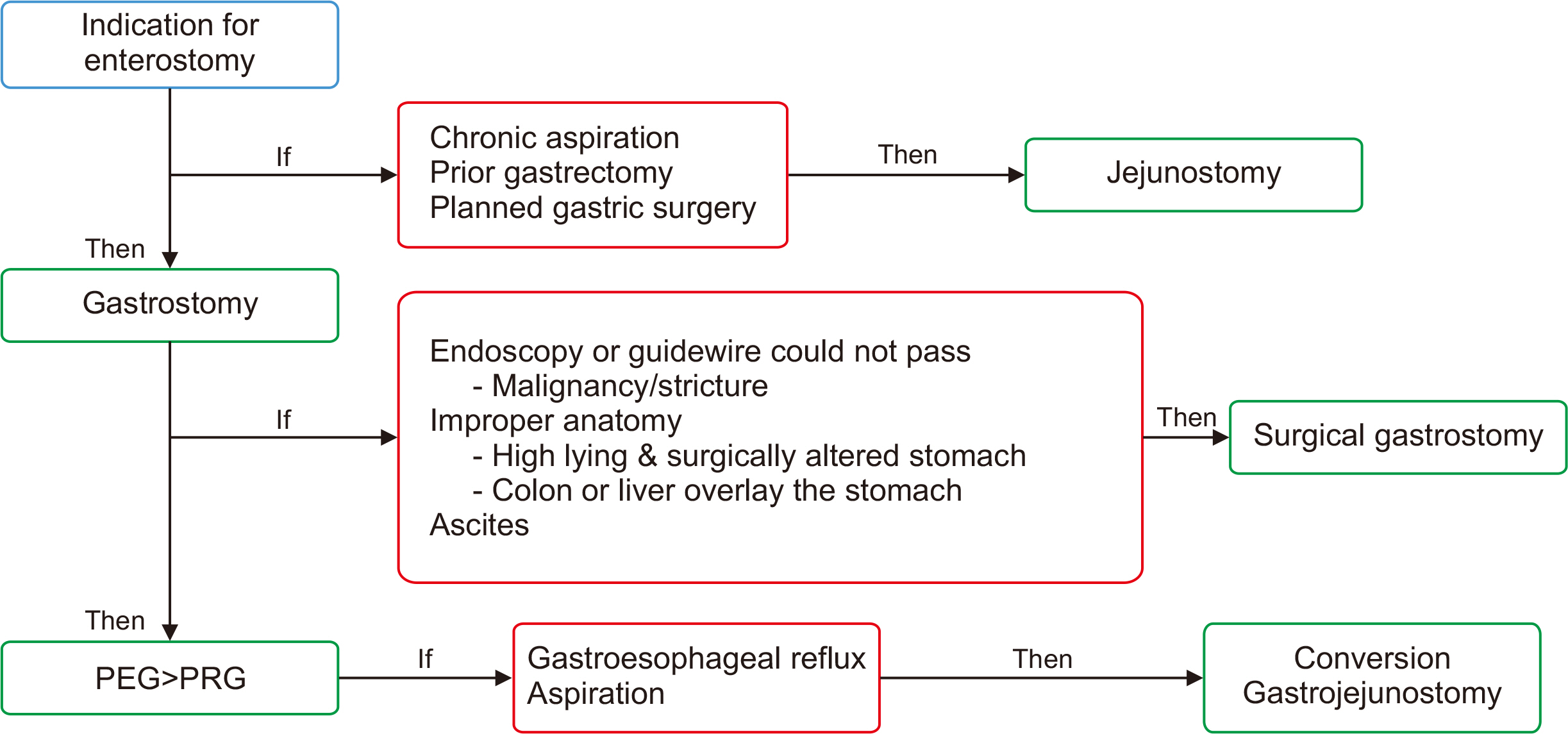

Enteral feeding is commonly used in patients who have a functional intestine but cannot achieve nutritional requirements via oral intake. Enteral feeding may be used for short-term periods, mainly among hospitalized patients, or for long-term periods in home care settings. When using enteral access, the duration of enteral feeding and the clinical characteristics of the patients should be considered (Fig. 2). In most cases, gastrostomy feeding is appropriate except in patients with chronic aspiration, a previous history of gastrectomy, or planned gastric surgery. In such cases, jejunostomy feeding should be considered. After the 1980s, PEG or PRG replaced surgical gastrostomy as the procedure of choice for long-term EN supply. However, surgical gastrostomy should be considered for patients in whom an endoscope or guidewire cannot be passed or for those with abnormal anatomy. If the patients have a history or risk of gastroesophageal reflux or aspiration after gastrostomy, conversion gastrojejunostomy may be considered.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author of this manuscript has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FUNDING

None.

Fig. 1

Enterostomy feeding route. (A) Gastrostomy. (B) Jejunostomy: the tip of the tube is located in the second jejunal loop. (C) Gastrojejunostomy: the gastrojejunal tube is inserted via the gastrostomy site.

Fig. 2

Selection of the enterostomy feeding route for enteral nutrition.

PEG = percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PRG = percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy.

Table 1

Indications for enterostomy tube feeding

Table 2

Contraindications for enterostomy tube feeding

- 1. Pritchard C, Duffy S, Edington J, Pang F. Enteral nutrition and oral nutrition supplements: a review of the economics literature. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2006;30:52-9. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 2. Heyland DK, Stephens KE, Day AG, McClave SA. The success of enteral nutrition and ICU-acquired infections: a multicenter observational study. Clin Nutr 2011;30:148-55. ArticlePubMed

- 3. Freeman C, Ricevuto A, DeLegge MH. Enteral nutrition in patients with dementia and stroke. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010;26:156-9. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Al-Zubeidi D, Rahhal RM. Safety techniques for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in Pierre Robin Sequence. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2011;35:343-5. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Gramlich L, Kichian K, Pinilla J, Rodych NJ, Dhaliwal R, Heyland DK. Does enteral nutrition compared to parenteral nutrition result in better outcomes in critically ill adult patients? A systematic review of the literature. Nutrition 2004;20:843-8. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Masiero S, Pierobon R, Previato C, Gomiero E. Pneumonia in stroke patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia: a six-month follow-up study. Neurol Sci 2008;29:139-45. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 7. Pancorbo-Hidalgo PL, García-Fernandez FP, Ramírez-Pérez C. Complications associated with enteral nutrition by nasogastric tube in an internal medicine unit. J Clin Nurs 2001;10:482-90. ArticlePubMed

- 8. Hamidon BB, Abdullah SA, Zawawi MF, Sukumar N, Aminuddin A, Raymond AA. A prospective comparison of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and nasogastric tube feeding in patients with acute dysphagic stroke. Med J Malaysia 2006;61:59-66.PubMed

- 9. Norton B, Homer-Ward M, Donnelly MT, Long RG, Holmes GK. A randomised prospective comparison of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and nasogastric tube feeding after acute dysphagic stroke. BMJ 1996;312:13-6. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Kozeniecki M, Fritzshall R. Enteral nutrition for adults in the hospital setting. Nutr Clin Pract 2015;30:634-51. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 11. Löser C, Aschl G, Hébuterne X, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Muscaritoli M, Niv Y, et al. ESPEN guidelines on artificial enteral nutrition--percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Clin Nutr 2005;24:848-61. PubMed

- 12. Deane AM, Adam MD, Dhaliwal R, Rupinder D, Day AG, Andrew GD, et al. Comparisons between intragastric and small intestinal delivery of enteral nutrition in the critically ill: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2013;17:R125.PubMedPMC

- 13. Hsu CW, Sun SF, Lin SL, Kang SP, Chu KA, Lin CH, et al. Duodenal versus gastric feeding in medical intensive care unit patients: a prospective, randomized, clinical study. Crit Care Med 2009;37:1866-72. ArticlePubMed

- 14. Baltz JG, Argo CK, Al-Osaimi AM, Northup PG. Mortality after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in patients with cirrhosis: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:1072-5. ArticlePubMed

- 15. Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ Jr. Gastrostomy without laparotomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg 1980;15:872-5. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Hull MA, Rawlings J, Murray FE, Field J, McIntyre AS, Mahida YR, et al. Audit of outcome of long-term enteral nutrition by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Lancet 1993;341:869-72. ArticlePubMed

- 17. Hoepffner N, Schröder O, Stein J. Enteral nutrition by endoscopic means; II. Complications and management. Z Gastroenterol 2004;42:1393-8. ArticlePubMed

- 18. Wicks C, Gimson A, Vlavianos P, Lombard M, Panos M, Macmathuna P, et al. Assessment of the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding tube as part of an integrated approach to enteral feeding. Gut 1992;33:613-6. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Pearce CB, Goggin PM, Collett J, Smith L, Duncan HD. The ‘cut and push’ method of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube removal. Clin Nutr 2000;19:133-5. ArticlePubMed

- 20. Preshaw RM. A percutaneous method for inserting a feeding gastrostomy tube. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1981;152:658-60.PubMed

- 21. Sinclair JJ, Scolapio JS, Stark ME, Hinder RA. Metastasis of head and neck carcinoma to the site of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: case report and literature review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2001;25:282-5. ArticlePubMed

- 22. Laasch HU, Martin DF. Radiologic gastrostomy. Endoscopy 2007;39:247-55. ArticlePubMed

- 23. Murayama KM, Schneider PD, Thompson JS. Laparoscopic gastrostomy: a safe method for obtaining enteral access. J Surg Res 1995;58:1-5. ArticlePubMed

- 24. Lydiatt DD, Murayama KM, Hollins RR, Thompson JS. Laparoscopic gastrostomy versus open gastrostomy in head and neck cancer patients. Laryngoscope 1996;106:407-10. ArticlePubMed

- 25. Mizrahi I, Garg M, Divino CM, Nguyen S. Comparison of laparoscopic versus open approach to gastrostomy tubes. JSLS 2014;18:28-33. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 26. Toussaint E, Van Gossum A, Ballarin A, Le Moine O, Estenne M, Knoop C, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy in patients with gastroparesis following lung transplantation: feasibility and clinical outcome. Endoscopy 2012;44:772-5. ArticlePubMed

- 27. Maple JT, Petersen BT, Baron TH, Gostout CJ, Wong Kee Song LM, Buttar NS. Direct percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy: outcomes in 307 consecutive attempts. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:2681-8. ArticlePubMed

- 28. Pearce CB, Duncan HD. Enteral feeding. Nasogastric, nasojejunal, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, or jejunostomy: its indications and limitations. Postgrad Med J 2002;78:198-204. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 29. Kim CY, Dai R, Wang Q, Ronald J, Zani S, Smith TP. Jejunostomy tube insertion for enteral nutrition: comparison of outcomes after laparoscopic versus radiologic insertion. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2020;31:1132-8. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Hoffer EK, Cosgrove JM, Levin DQ, Herskowitz MM, Sclafani SJ. Radiologic gastrojejunostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a prospective, randomized comparison. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1999;10:413-20. ArticlePubMed

- 31. Olson DL, Krubsack AJ, Stewart ET. Percutaneous enteral alimentation: gastrostomy versus gastrojejunostomy. Radiology 1993;187:105-8. ArticlePubMed

- 32. Given MF, Hanson JJ, Lee MJ. Interventional radiology techniques for provision of enteral feeding. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2005;28:692-703. ArticlePubMedPDF

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Preprocedural prognostic nutritional index predicts early gastrointestinal symptoms after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy in Korea: a retrospective cohort study

Yoonhong Kim, Jee Young Lee, Yeajin Moon, Seung Hun Lee, Kyung Won Seo, Ki Hyun Kim

Ann Clin Nutr Metab.2025; 17(3): 196. CrossRef

Selection of the Enterostomy Feeding Route in Enteral Nutrition

Fig. 1

Enterostomy feeding route. (A) Gastrostomy. (B) Jejunostomy: the tip of the tube is located in the second jejunal loop. (C) Gastrojejunostomy: the gastrojejunal tube is inserted via the gastrostomy site.

Fig. 2

Selection of the enterostomy feeding route for enteral nutrition.

PEG = percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PRG = percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Selection of the Enterostomy Feeding Route in Enteral Nutrition

Indications for enterostomy tube feeding

| Indications |

|---|

| General indications for enterostomy |

| Swallowing disorder from stroke or other neurologic disorders |

| Neoplastic disease of the head, neck, and mediastinum |

| Esophageal fistula caused by recent surgery or trauma |

| Esophageal stricture |

| Indications for jejunostomy |

| Severe gastroesophageal reflux |

| Gastroparesis |

| Gastric outlet obstruction |

| Gastric or duodenal fistula |

| Altered anatomy from prior gastric surgery |

| When stomach is to undergo later surgery |

Contraindications for enterostomy tube feeding

| Contraindications |

|---|

| Absolute contraindications |

| Dysfunctional digestive tract (mechanical obstruction, paralytic ileus) |

| Peritonitis |

| Mesenteric ischemia |

| Severe coagulopathy |

| Abdominal wall defects |

| Relative contraindications |

| Ascites |

| Gastric ulcer |

| Ventriculo-peritoneal shunts |

| Presence of -stomies, drain tubes, or surgical scars |

Table 1

Indications for enterostomy tube feeding

Table 2

Contraindications for enterostomy tube feeding

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN Cite

Cite