Scopus, KCI, KoreaMed

Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Clin Nutr Metab > Volume 17(3); 2025 > Article

- Original Article Preprocedural prognostic nutritional index predicts early gastrointestinal symptoms after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy in Korea: a retrospective cohort study

-

Yoonhong Kim1,*

, Jee Young Lee2,*

, Jee Young Lee2,* , Yeajin Moon1

, Yeajin Moon1 , Seung Hun Lee1

, Seung Hun Lee1 , Kyung Won Seo1

, Kyung Won Seo1 , Ki Hyun Kim1

, Ki Hyun Kim1

-

Annals of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism 2025;17(3):196-202.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15747/ACNM.25.0032

Published online: December 1, 2025

1Department of Surgery, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea

2Nutrition Support Team, Department of Nursing, Kosin University Gospel Hospital, Busan, Korea

- Corresponding author: Ki Hyun Kim e-mail: linus.kkh@gmail.com

Yoonhong Kim and Jee Young Lee contributed equally as co-first authors.

© 2025 The Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition · The Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition · Asian Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 868 Views

- 19 Download

Abstract

-

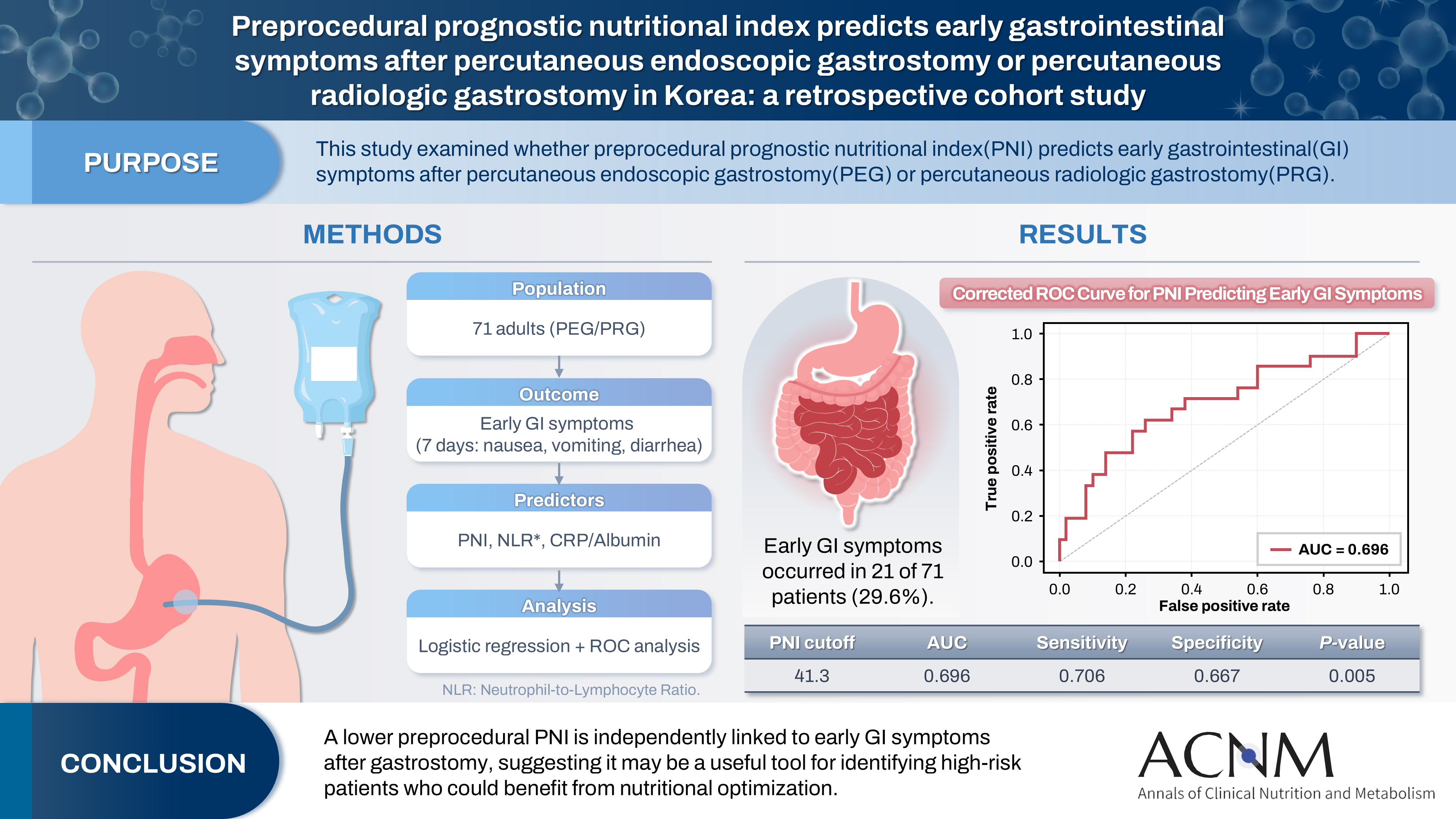

Purpose The prognostic nutritional index (PNI) reflects immunonutritional status and is a well-established predictor of surgical outcomes. Although its association with post-gastrostomy mortality has been documented, its relationship with early gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms remains unclear. This study aimed to evaluate whether the preprocedural PNI predicts early GI symptoms following percutaneous gastrostomy, including percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) and percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy (PRG).

-

Methods This retrospective study included 71 adults who underwent PEG or PRG. Early GI symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, occurring within 7 days were recorded. The preprocedural PNI, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and the C-reactive protein (CRP)-to-albumin ratio were analyzed using logistic regression to identify predictors. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to assess the PNI’s discriminative performance.

-

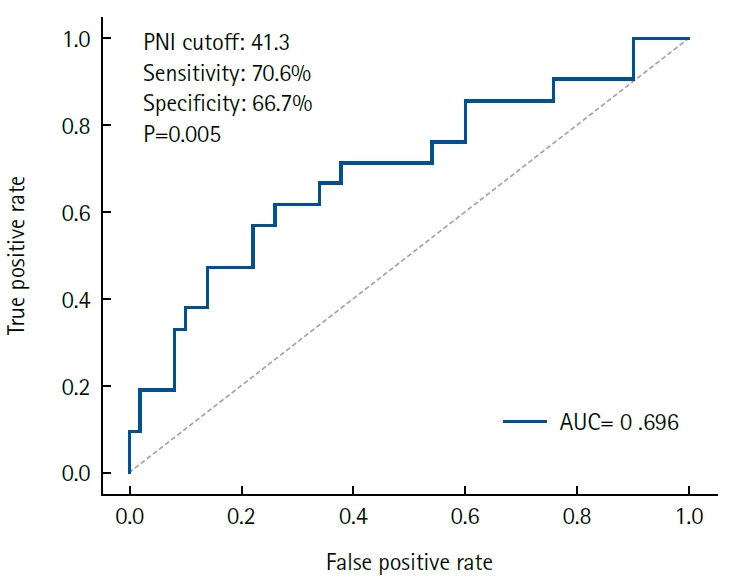

Results Early GI symptoms occurred in 21 of 71 patients (29.6%). In univariate analysis, the PNI (P=0.009) and CRP-to-albumin ratio (P=0.018) were significant predictors, whereas NLR was not (P=0.125). After adjustment for potential confounders, including age, sex, body mass index, and NLR, the PNI remained an independent predictor of early GI symptoms (adjusted odds ratio, 0.90; 95% confidence interval, 0.83–0.98; P=0.021). ROC analysis for the PNI produced an area under the curve of 0.696, with an optimal cutoff value of 41.3 (sensitivity 70.6%, specificity 66.7%).

-

Conclusion A lower preprocedural PNI is independently associated with the development of early GI symptoms after gastrostomy. The PNI may serve as a practical screening tool to identify high-risk patients who could benefit from preemptive nutritional optimization.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: JYL. Data curation: YK, YM. Methodology/formal analysis/validation: YM, SHL. Project administration: KHK. Writing–original draft: YK. JYL. Writing–review & editing: YM, SHL, KWS, KHK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Contact the corresponding author for data availability.

Acknowledgments

None.

Supplementary materials

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with and without early GI symptoms following PEG/PRG.

GI, gastrointestinal; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PRG, percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy; LOS, length of stay; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

P-values were determined using Student t test or chi-square test, as applicable.

The multivariate logistic regression model included variables considered clinically fundamental or those showing a strong trend in univariate analysis (e.g., age, BMI, PNI). Variables such as serum albumin, HS-CRP, and CRP-to-albumin ratio were excluded from the final multivariate model—despite their univariate significance—to avoid multicollinearity. This is because PNI and the CRP-to-albumin ratio are composite indices calculated from serum albumin and/or CRP, leading to statistical interference when included simultaneously. NLR was also excluded due to its lack of significant association in the univariate analysis.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; HS-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Serum albumin | 0.266 (0.093–0.763) | 0.014 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count | 0.999 (0.998–1.000) | 0.083 |

| Absolute neutrophil count | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.970 |

Univariate logistic regression analysis for the individual components of PNI (serum albumin, absolute lymphocyte count) and NLR (absolute neutrophil count, absolute lymphocyte count) to identify the primary driver of the association with GI symptoms.

PNI, prognostic nutritional index; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; GI, gastrointestinal; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

- 1. Zhang L, Ma W, Qiu Z, Kuang T, Wang K, Hu B, et al. Prognostic nutritional index as a prognostic biomarker for gastrointestinal cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front Immunol 2023;14:1219929.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Adachi Y, Akino K, Nojima M, Himori R, Kikuchi T, Mita H, et al. Prognostic nutritional index and early mortality with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. QJM 2018;111:635-41. ArticlePubMed

- 3. Ayman AR, Khoury T, Cohen J, Chen S, Yaari S, Daher S, et al. Peg insertion in patients with dementia does not improve nutritional status and has worse outcomes as compared with peg insertion for other indications. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017;51:417-20. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Han DS. Selection of the enterostomy feeding route in enteral nutrition. Ann Clin Nutr Metab 2022;14:50-4. Article

- 5. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration-a Korean translation. Ewha Med J 2024;47:e31.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 6. Zahorec R. Ratio of neutrophil to lymphocyte counts: rapid and simple parameter of systemic inflammation and stress in critically ill. Bratisl Lek Listy 2001;102:5-14. ArticlePubMed

- 7. Guo Y, Cai K, Mao S, Zhang J, Wang L, Zhang Z, et al. Preoperative C-reactive protein/albumin ratio is a significant predictor of survival in bladder cancer patients after radical cystectomy: a retrospective study. Cancer Manag Res 2018;10:4789-804. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 8. Onodera T, Goseki N, Kosaki G. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi 1984;85:1001-5. ArticlePubMed

- 9. Uri I, Horvath A, Tamas L, Polony G, Danos K. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI) correlates with survival in head and neck cancer patients more precisely than other nutritional markers: real world data. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2024;281:6599-611. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 10. Li P, Lai Y, Tian L, Zhou Q. The prognostic value of prognostic nutritional index in advanced cancer receiving PD-1/L1 inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Cancer Med 2022;11:3048-56. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Cadwell JB, Afonso AM, Shahrokni A. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI), independent of frailty is associated with six-month postoperative mortality. J Geriatr Oncol 2020;11:880-4. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Lu Y, Ren C, Jiang J. The relationship between prognostic nutritional index and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients: a retrospective study. Int J Gen Med 2021;14:3619-26. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 13. Saunders J, Smith T. Malnutrition: causes and consequences. Clin Med (Lond) 2010;10:624-7. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Idasiak-Piechocka I, Lewandowski D, Swigut W, Kalinowski J, Mikosza K, Suchowiejski P, et al. Effect of hypoalbuminemia on drug pharmacokinetics. Front Pharmacol 2025;16:1546465.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Doherty WL, Winter B. Prokinetic agents in critical care. Crit Care 2003;7:206-8. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Lewis K, Alqahtani Z, Mcintyre L, Almenawer S, Alshamsi F, Rhodes A, et al. The efficacy and safety of prokinetic agents in critically ill patients receiving enteral nutrition: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care 2016;20:259.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Raphaeli O, Statlender L, Hajaj C, Bendavid I, Goldstein A, Robinson E, et al. Using machine-learning to assess the prognostic value of early enteral feeding intolerance in critically ill patients: a retrospective study. Nutrients 2023;15:2705.ArticlePubMedPMC

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Fig. 1.

Graphical abstract

| Variable | No GI symptoms (n=50) | GI symptoms (n=21) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean±SD | 65.1±14.6 | 68.0±11.0 | 0.356 |

| BMI (kg/m²), mean±SD | 19.6±2.7 | 19.8±3.4 | 0.814 |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 35 (70.0) | 17 (81.0) | 0.369 |

| Procedure type, No. (%) | 0.944 | ||

| PEG | 36 (72.0) | 16 (76.2) | |

| PRG | 14 (28.0) | 5 (23.8) | |

| LOS (day), mean±SD | 29.0±3.9 | 57.0±11.3 | <0.001 |

| Preprocedural LOS (day), mean±SD | 16.3±2.3 | 21.2±8.2 | 0.820 |

| Postprocedural LOS (day), mean±SD | 12.7±2.3 | 35.8±5.1 | <0.001 |

| PNI, mean±SD | 45.6±6.9 | 40.3±7.9 | 0.011 |

| NLR, mean±SD | 6.5±5.1 | 9.8±10.9 | 0.187 |

| Variable | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.404 | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | 0.963 |

| BMI | 1.02 (0.86–1.22) | 0.791 | 1.06 (0.86–1.30) | 0.593 |

| Sex | 0.80 (0.25–2.61) | 0.716 | 0.60 (0.16–2.23) | 0.445 |

| PNI | 0.90 (0.83–0.97) | 0.009 | 0.90 (0.83–0.98) | 0.021 |

| NLR | 1.06 (0.98–1.15) | 0.125 | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) | 0.491 |

| CRP-to-albumin ratio | 1.40 (1.06–1.85) | 0.018 | - | - |

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Serum albumin | 0.266 (0.093–0.763) | 0.014 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count | 0.999 (0.998–1.000) | 0.083 |

| Absolute neutrophil count | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.970 |

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with and without early GI symptoms following PEG/PRG. GI, gastrointestinal; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PRG, percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy; LOS, length of stay; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio. P-values were determined using Student t test or chi-square test, as applicable.

The multivariate logistic regression model included variables considered clinically fundamental or those showing a strong trend in univariate analysis (e.g., age, BMI, PNI). Variables such as serum albumin, HS-CRP, and CRP-to-albumin ratio were excluded from the final multivariate model—despite their univariate significance—to avoid multicollinearity. This is because PNI and the CRP-to-albumin ratio are composite indices calculated from serum albumin and/or CRP, leading to statistical interference when included simultaneously. NLR was also excluded due to its lack of significant association in the univariate analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; HS-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Univariate logistic regression analysis for the individual components of PNI (serum albumin, absolute lymphocyte count) and NLR (absolute neutrophil count, absolute lymphocyte count) to identify the primary driver of the association with GI symptoms. PNI, prognostic nutritional index; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; GI, gastrointestinal; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

Cite

Cite