Abstract

-

Purpose

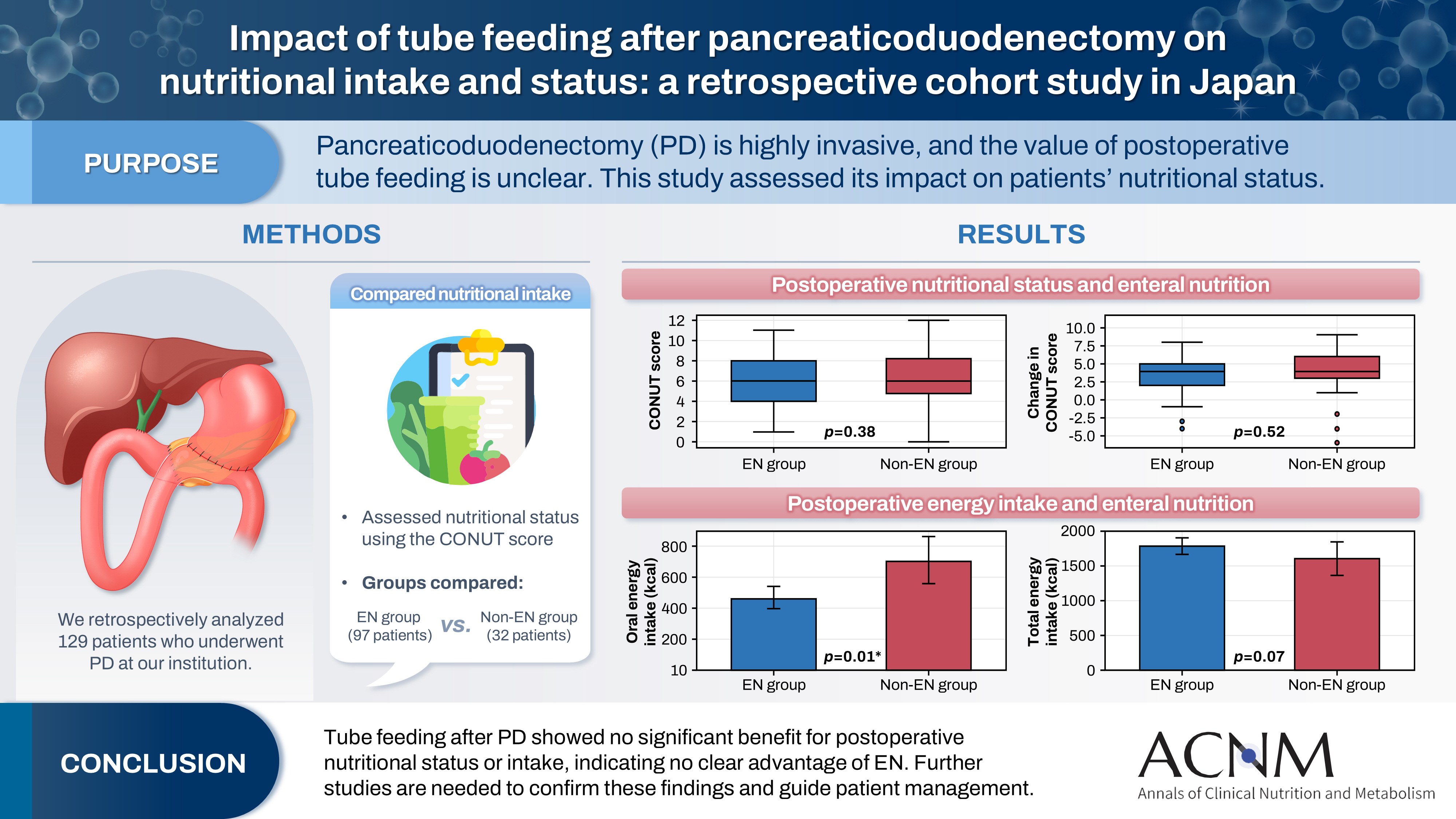

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is one of the most invasive procedures in gastrointestinal surgery. However, the clinical significance of postoperative tube feeding remains unclear. This study investigated the impact of enteral nutrition (EN) on the postoperative nutritional status of patients undergoing PD.

-

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 129 patients who underwent PD at Tohoku University Hospital. Nutritional intake and status, evaluated using the Controlling Nutritional Status score, were compared between two groups: an EN group (97 patients) and a non-EN group (32 patients).

-

Results

There were no significant differences between the two groups in age, sex, body mass index, underlying diseases, operative duration, blood loss, postoperative pancreatic fistula, postoperative complications, delayed gastric emptying, or length of hospital stay. Although the EN group showed improvements in nutritional status both at discharge and compared with preoperative values, none of these changes reached statistical significance. Oral caloric intake was significantly higher in the non-EN group (P=0.01). In contrast, total energy intake was higher in the EN group, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07).

-

Conclusion

Tube feeding after PD did not significantly influence postoperative nutritional status or overall nutritional intake. These findings suggest that EN offers no clear advantage over other approaches; however, further research is warranted to validate these results, refine existing guidelines, and optimize postoperative patient management.

-

Keywords: Enteral nutrition; Nutritional status; Pancreaticoduodenectomy; Postoperative complications; Treatment outcome

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Background

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is regarded as one of the most invasive procedures in gastrointestinal surgery. Postoperative complications such as pancreatic fistula, intra-abdominal hemorrhage, abscess formation, delayed gastric emptying, bile leakage, cholangitis, and surgical site infection occur at a relatively high frequency, with an incidence rate of 40% to 60%, which exceeds that of most other gastrointestinal operations [

1].

After PD, nutritional management via oral intake may become challenging due to complications such as pancreatic fistula, chylous ascites, or delayed gastric emptying [

2-

4]. Consequently, patients frequently experience a decline in postoperative nutritional status. Malnutrition has been associated with higher rates of postoperative complications [

5] and poorer quality of life [

6], underscoring the need for meticulous perioperative nutritional management to prevent or mitigate adverse outcomes.

When oral feeding is inadequate, enteral nutrition (EN) is generally preferred over parenteral nutrition. This preference is also supported by the guidelines of the Japanese Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism [

7]. EN is presumed beneficial for PD patients, who commonly experience postoperative difficulties with oral intake.

However, the 2019 edition of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pancreatic Cancer issued only a weak recommendation against the routine use of perioperative EN therapy [

8]. Furthermore, the updated 2022 edition omitted any reference to EN, stating that “routine perioperative enteral nutrition therapy is no longer standard clinical practice” [

9], reflecting an increasingly negative position toward the use of EN after PD.

This study aimed to clarify the effects of EN on postoperative nutritional status and clinical outcomes in patients who underwent PD at our institution. We sought to determine the clinical relevance and potential benefits of EN following PD.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was conducted as a subanalysis of the research project titled “Clinicopathological Factors and Treatment Outcomes in Pancreatic Diseases.” The study was approved by the Tohoku University Ethics Committee (No. 2017-1-089). Informed consent was waived because this was a retrospective chart review.

Study design

Setting

We analyzed cases of PD performed at the Department of General Surgery, Tohoku University Hospital, between January 2014 and June 2017. During this period, PD was generally conducted as subtotal stomach-preserving PD with reconstruction by a modified Child method. Gastrojejunostomy was performed using the Billroth II approach. In principle, all cases involved intraoperative insertion of an EN tube via the afferent limb, which was then fixed using the Witzel method. Postoperative management followed a standardized critical pathway [

3]. Water intake began on postoperative day 1, and meals were introduced from postoperative day 3. Additionally, beginning on postoperative day 3, 200 mL of elemental nutrition (1 kcal/mL) was administered through the EN tube, which was increased to 600 mL/day by postoperative day 5. Oral intake was prioritized for energy supply, with enteral or parenteral nutrition added as needed to meet individual caloric requirements. When oral intake was adequate, enteral and parenteral nutrition were gradually reduced. In cases presenting with symptoms suggestive of intolerance to enteral feeding, such as abdominal distension or diarrhea, EN was decreased, while oral or parenteral nutrition was increased accordingly.

Patients with a history of gastric resection other than total gastrectomy (e.g., distal or proximal gastrectomy) and those experiencing difficulty with oral intake due to delayed gastric emptying were included. The exclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) cases with simultaneous major hepatectomy; (2) cases with total pancreatectomy due to PD; (3) cases with a history of total gastrectomy; (4) cases requiring reoperation after postoperative day 7; and (5) cases with a period of fasting due to postoperative complications such as aspiration pneumonia, anastomotic leakage, or chylous ascites.

Variables

For the included cases, data on age, sex, height, weight, diagnosis, operative procedure, operative time, blood loss, presence of pancreatic fistula, postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and results of blood biochemical tests were extracted from departmental databases and electronic medical records. Additionally, oral intake during hospitalization, total energy intake (including EN and intravenous fluids), and the presence of vomiting were recorded.

Data sources and measurements

To compare patient demographics, perioperative outcomes, postoperative course, nutritional status, and compare EN use retrospectively, patients who received ≥600 mL/day of EN within 1 week after surgery were categorized into the EN group, while those who did not receive this amount were classified as the non-EN group.

Delayed gastric emptying was classified according to the definition proposed by Wente et al. [

4]. Pancreatic fistula was defined using the International Study Group (ISGPF) grading system [

10], with Grade B or higher considered a clinical pancreatic fistula. Postoperative complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [

11], with Grade IIIA or higher regarded as significant complications. Cases with complications of Grade IIIB or higher were excluded, as these patients required fasting management.

Nutritional status was assessed using the Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score, which evaluates serum albumin, peripheral lymphocyte count, and serum cholesterol levels. The total CONUT score classifies nutritional status as normal (0–1), mild (2–4), moderate (5–8), or severe (9–12) [

12]. We have previously demonstrated the usefulness of the CONUT score in evaluating nutritional status and predicting complications following pancreatic resection [

5,

13], and it is currently used at our institution for perioperative nutritional assessment.

Postoperative energy requirements were calculated by first determining basal energy expenditure using the Harris-Benedict equation based on standard body weight [

14], which was then multiplied by an activity factor and a stress factor of 1.5. The postoperative energy fulfillment rate was derived by dividing the actual energy intake by the calculated postoperative energy requirement.

Confounding bias could not be fully excluded because decisions regarding the initiation or omission of EN were not randomized but based on clinical judgment and individual patient conditions. Although baseline demographics and operative factors were compared between groups, residual confounding due to unmeasured factors—such as comorbidities, perioperative inflammation, or functional status—may persist. Furthermore, survivorship bias may have been introduced, as patients with severe early postoperative complications were excluded, potentially underestimating both the risks and potential benefits of EN.

Study size

No formal sample size calculation was performed because all eligible patients during the study period were included in the analysis.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Continuous variables, including age, body mass index (BMI), blood loss, operative time, postoperative hospital stay, and CONUT score, were expressed as median (interquartile range). Energy intake was presented as mean (95% confidence interval). Comparisons between groups were conducted using the Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables (sex, underlying disease, clinical pancreatic fistula, postoperative complications, and delayed gastric emptying). A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants

A total of 129 patients were included in the analysis, with a median age of 68 years (interquartile range, 61–74 years). The cohort comprised 83 men and 46 women. The underlying disease was pancreatic cancer in 55 cases. The EN group, defined as patients who received ≥600 mL/day of EN within 1 week postoperatively, included 97 cases, while the non-EN group comprised 32 cases. The cumulative energy intake via EN during the first postoperative week was significantly higher in the EN group (P<0.01). Clinical characteristics were compared between the two groups (

Table 1).

No significant differences were observed between the EN and non-EN groups with respect to age, sex, BMI, underlying disease (pancreatic cancer), blood loss, or operative time (

Table 1). Although the P-value for BMI was 0.05, the absolute difference between groups was small and not clinically meaningful.

A comparison of postoperative complications revealed no significant differences between the groups in the incidence of clinical pancreatic fistula, complications of Clavien-Dindo Grade IIIA or higher, or delayed gastric emptying. Likewise, there was no significant difference in postoperative hospital stay between the two groups.

We next examined differences in nutritional status during hospitalization and at discharge, as well as detailed patterns of energy intake, according to the presence or absence of EN.

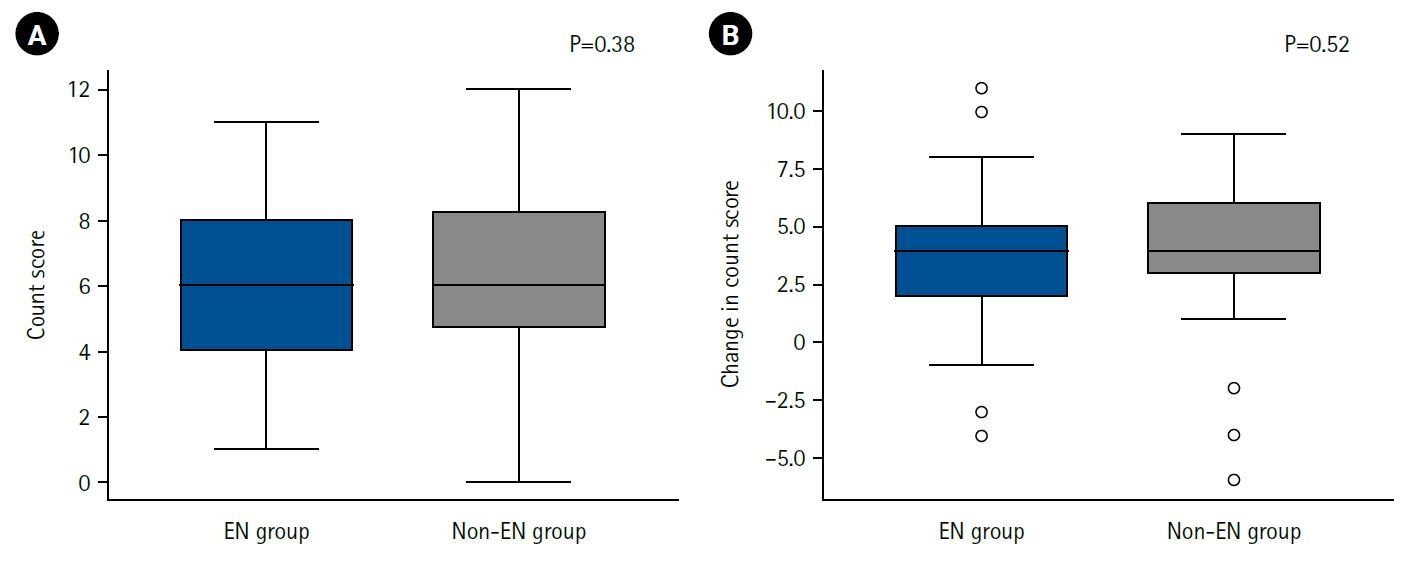

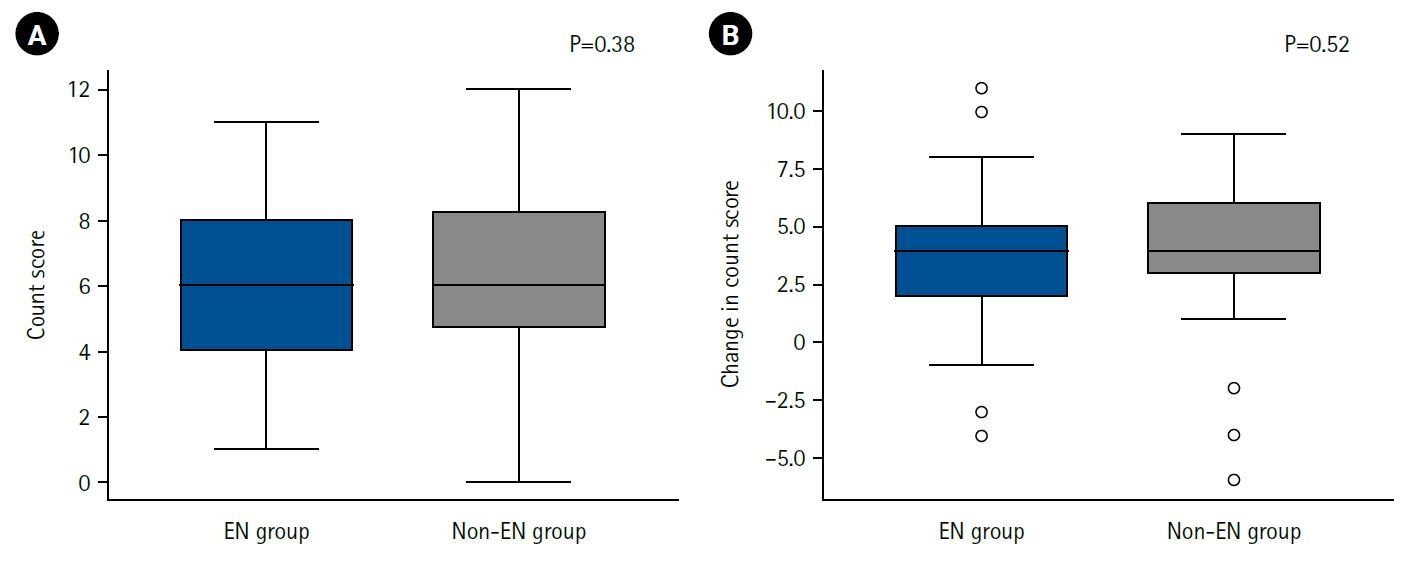

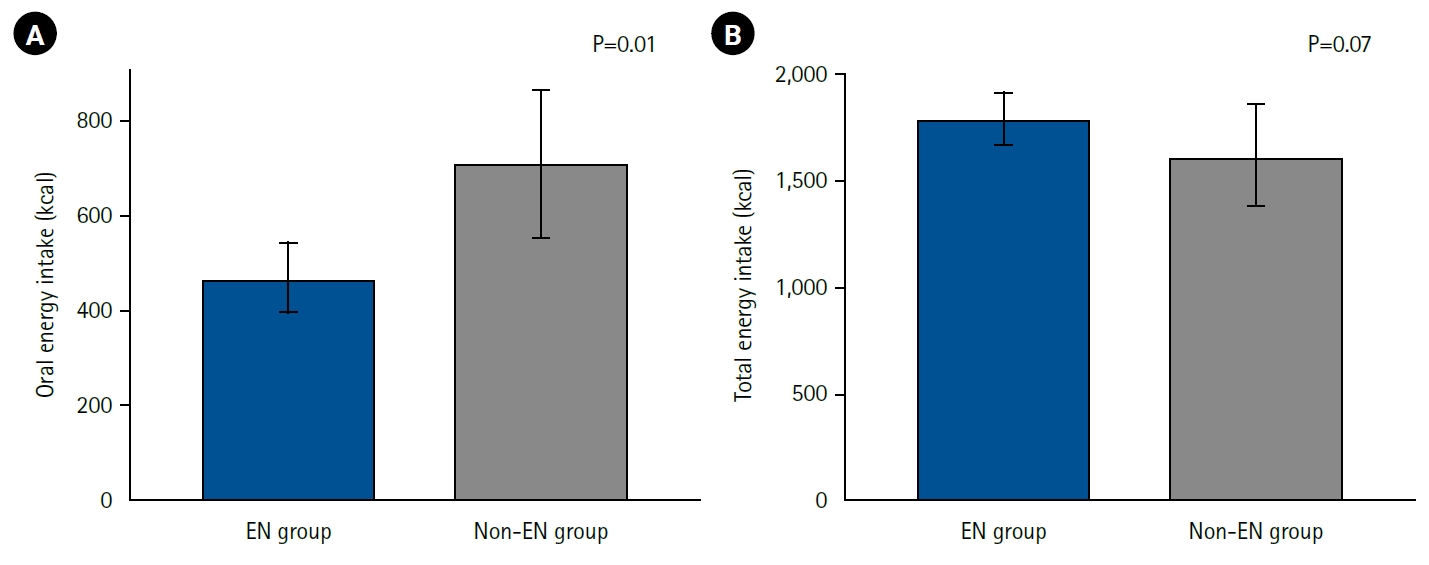

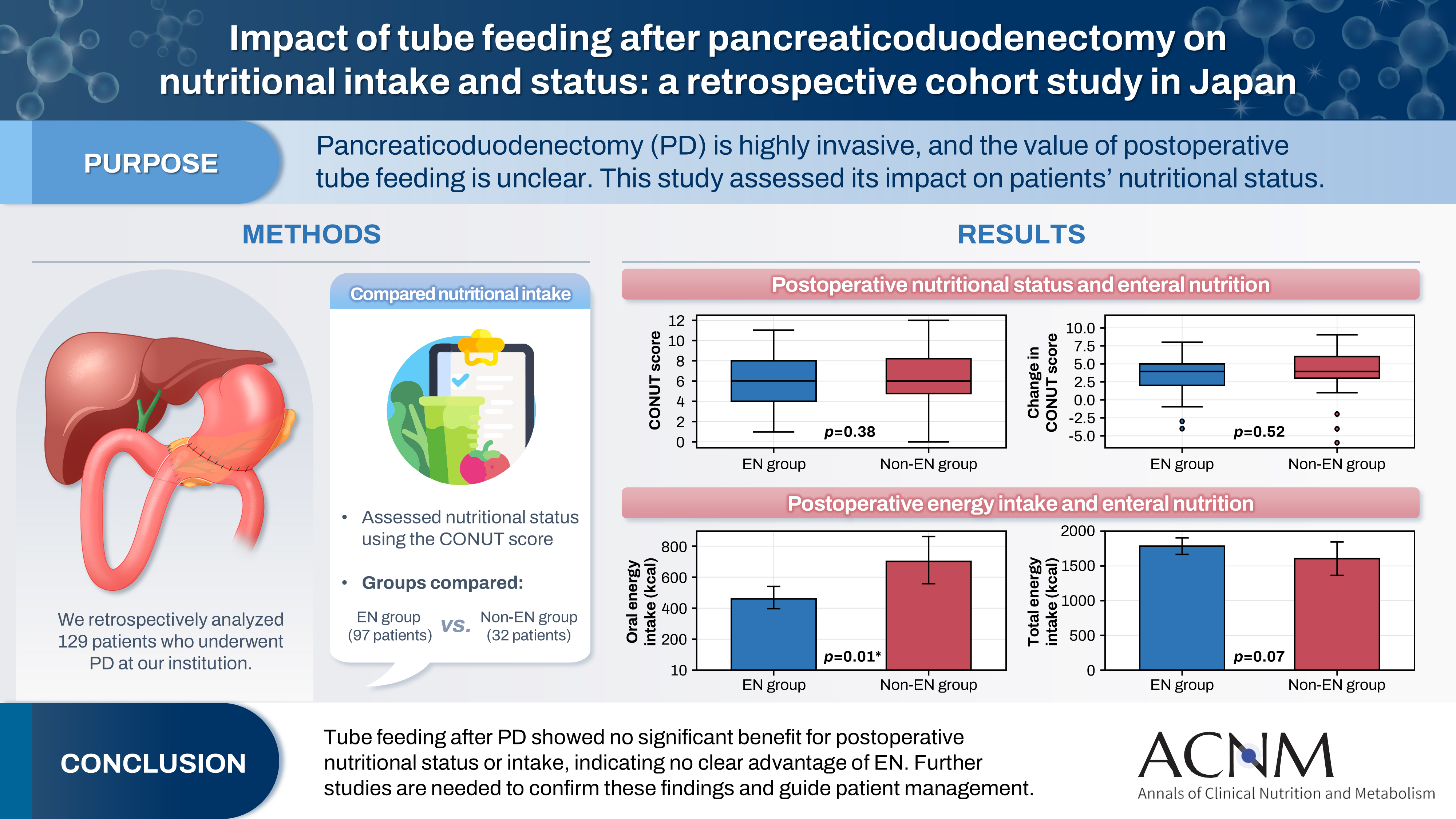

A comparison of CONUT scores at discharge showed no clear difference between the EN and non-EN groups (

Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the change in CONUT score between admission and discharge (ΔCONUT) did not differ significantly between groups (

Fig. 1B).

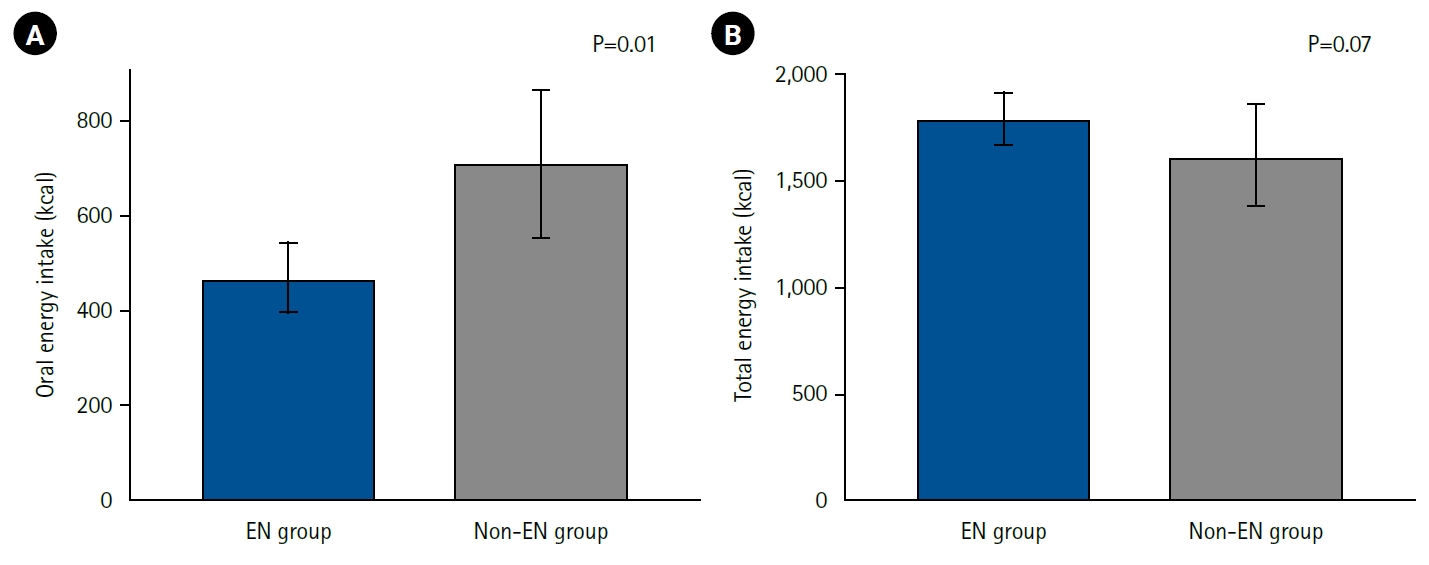

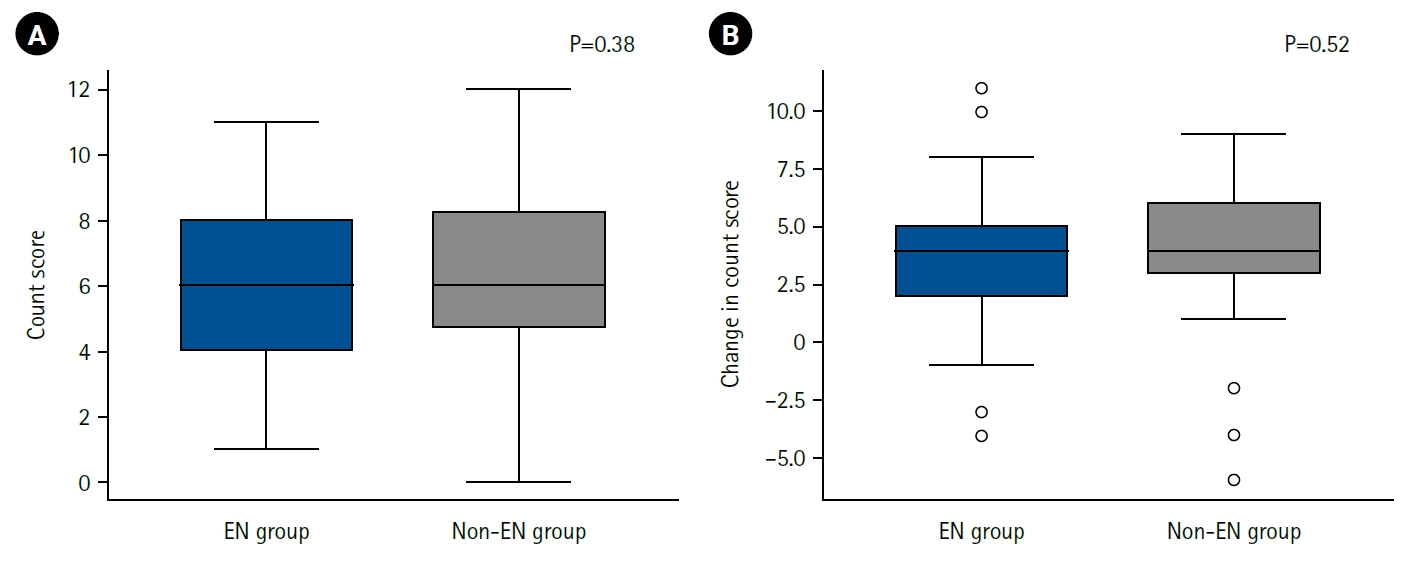

Energy intake during the first postoperative week was analyzed by route and compared between the EN and non-EN groups (

Fig. 2). Oral energy intake was significantly higher in the non-EN group (EN group: 467 kcal and non-EN group: 711 kcal; P=0.01), indicating that patients in the non-EN group obtained more energy from meals. Total energy intake (parenteral plus enteral) showed no significant difference between the groups, although there was a trend toward higher intake in the EN group (EN group: 1,796 kcal and non-EN group: 1,617 kcal; P=0.07). The energy fulfillment rate was 93% in the EN group and 73% in the non-EN group, again showing a nonsignificant trend toward higher values in the EN group (P=0.06).

Discussion

Key results

In this study, EN after PD did not demonstrate a clear effect on postoperative nutritional status. This may be explained by the fact that patients with lower EN intake had higher oral intake or received supplemental parenteral nutrition, leading to minimal differences between groups, with total energy intake remaining similar at approximately 1,500 kcal in both. Moreover, the presence or absence of EN was not associated with postoperative complications or length of hospital stay. Therefore, a strong recommendation for routine EN after PD cannot be made. Nonetheless, in patients with limited postoperative oral intake, EN may help prevent deterioration in nutritional status.

Interpretation/comparison with previous studies

The role of EN after PD remains a matter of debate. The 2019 edition of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pancreatic Cancer issued only a weak recommendation against perioperative EN after pancreatic resection [

8], while the most recent 2022 edition removed any mention of EN, stating that “routine perioperative enteral nutrition therapy is no longer standard clinical practice” [

9]. The 2019 guideline’s rationale for discouraging EN included the absence of significant differences in postoperative complications and, in one multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT), an apparent increase in complications in the EN group [

15]. However, that RCT reported a high-mortality rate of approximately 6%, compared with rates below 3% in other studies, raising concerns about the validity of uniform interpretation. When that high-mortality study was excluded, a meta-analysis performed for the 2019 guideline showed significantly fewer postoperative complications in the EN group (P=0.01).

A 2019 meta-analysis investigating early EN after PD reported no significant difference in postoperative complications but did show a shorter hospital stay in the EN group [

16]. More recent systematic reviews have suggested that EN after PD may reduce hospital stay, though its impact on postoperative complications remains uncertain; hence, selective rather than routine use is recommended [

17,

18].

Although EN is expected to help maintain adequate nutritional status following PD—particularly when oral intake is limited due to delayed gastric emptying—this study did not identify any significant association between EN and postoperative nutritional outcomes. This finding may reflect the compensatory role of higher oral or parenteral intake among patients with reduced EN administration, resulting in comparable total energy intake and similar nutritional outcomes. These observations imply that even when EN is limited, adequate postoperative nutritional support can still be achieved through alternative oral or parenteral routes.

While EN after PD may not confer substantial nutritional advantages, it can still serve practical purposes. The enteral route allows for the administration of medications and fluids in patients who have difficulty with oral intake due to delayed gastric emptying or bowel obstruction. In such cases, drugs that would otherwise be taken orally can sometimes be administered enterally, and fluids can be delivered via the feeding tube, thereby reducing the need for intravenous access. This may be particularly beneficial for patients with limited peripheral venous access.

Limitations

This study focused exclusively on postoperative nutritional status. Future research should also evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of EN after PD from the perspectives of drug and fluid administration. As a retrospective single-center study, it is inherently subject to selection bias, measurement bias due to the use of chart-based data, and residual confounding from unmeasured variables. Additionally, excluding patients with severe postoperative complications may have introduced survivorship bias. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution, and further prospective, multicenter studies are needed for validation.

Conclusion

This study found no evidence supporting the benefit of EN in improving postoperative nutritional status or total nutritional intake after PD. These results may reflect compensatory energy intake via alternative routes—such as oral or parenteral nutrition—in patients with limited EN administration, thereby minimizing nutritional differences between groups.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization/Data curation/Formal analysis: all authors. Investigation/Methodology/Project administration/Resources: all authors. Supervision: MU. Validation: all authors. Writing–original draft: all authors. Writing–review: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Contact the corresponding author for research data availability.

Acknowledgments

None.

Supplementary materials

None.

Fig. 1.Postoperative nutritional status and enteral nutrition. Nutritional status at discharge (A) and changes in nutritional status before and after hospitalization (B), assessed using the CONUT method, in the enteral nutrition group (EN group) and the non-enteral nutrition group (non-EN group). On the vertical axis, a higher CONUT score indicates poorer nutritional status (A), while a greater change in CONUT score represents a greater decline in nutritional status (B). No significant differences were observed between the two groups. CONUT, Controlling Nutritional Status.

Fig. 2.Postoperative energy intake and enteral nutrition. Energy intake from oral sources (A) and total energy intake including enteral nutrition and parenteral nutrition (B) during the first postoperative week in the enteral nutrition group (EN group) and non-enteral nutrition group (non-EN group) are shown. Oral energy intake was significantly higher in the non-EN group, but there was no significant difference in total energy intake between the groups, with rather a trend toward higher intake in the EN group.

Table 1.Patient factors, surgical factors, postoperative complications, and EN

|

Variable |

EN group (n=97) |

Non-EN group (n=32) |

P-value |

|

Cumulative EN (kcal)a

|

2,918 |

2,131 |

<0.01 |

|

Age (yr), median (IQR) |

68 (62–74) |

67 (59–72) |

0.20 |

|

Sex, No. (%) |

|

|

0.55 |

|

Male |

61 (62.9) |

22 (68.7) |

|

|

Female |

36 (37.1) |

10 (31.2) |

|

|

Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR) |

22 (20–25) |

21 (19–23) |

0.05 |

|

Primary disease, No. (%) |

|

|

0.65 |

|

Pancreatic cancer |

39 (40.2) |

16 (50.0) |

|

|

Others |

58 (59.8) |

16 (50.0) |

|

|

Blood loss (mL), median (IQR) |

1,065 (718–1,498) |

1,010 (784–1,288) |

0.34 |

|

Operative time (min), median (IQR) |

551 (483–620) |

537 (475–634) |

0.84 |

|

Clinical pancreatic fistula, No. (%) |

35 (36.1) |

11 (34.4) |

0.86 |

|

Postoperative complications, No. (%) |

47 (48.5) |

13 (40.6) |

0.45 |

|

Delayed gastric emptying, No. (%) |

58 (60.8) |

15 (46.9) |

0.20 |

|

Postoperative hospital stay (day), median (IQR) |

33 (23–44) |

31 (20–45) |

0.48 |

References

- 1. Aoki S, Miyata H, Konno H, Gotoh M, Motoi F, Kumamaru H, et al. Risk factors of serious postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy and risk calculators for predicting postoperative complications: a nationwide study of 17,564 patients in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2017;24:243-51. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 2. Mori A, Takashima Y. Current nutritional status of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Proc Jpn Nurs Assoc Adult Nurs I 2012;42:122-5.Article

- 3. Egawa S, Motoi F, Otsutome S. Reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy: focusing on anastomosis methods. Gastroenterol Surg 2008;31:1255-61.Article

- 4. Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2007;142:761-8. ArticlePubMed

- 5. Ishida M, Motoi F, Sato H, Murakami M, Maeda S, Kudoh K, et al. Preoperative nutritional assessment by CONUT (Controlling Nutritional Status) and postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Jpn Soc Parenter Enter Nutr 2018;33:641-6.Article

- 6. Sato N, Motoi F, Ariake K, Nakagawa K, Kawaguchi K, Sato M, et al. Chronological evaluation of postoperative nutritional status and quality of life of pancreatic cancer patients. Suizo 2017;32:873-81. Article

- 7. Japanese Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism. JSPEN Textbook. Nankodo; 2021.Article

- 8. Committee for the Revision of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pancreatic Cancer; Japan Pancreas Society. Clinical practice guidelines for pancreatic cancer (2019 edition). Kanehara Publishing; 2019.Article

- 9. Committee for the Revision of the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pancreatic Cancer; Japan Pancreas Society. Clinical practice guidelines for pancreatic cancer (2022 edition). Kanehara Publishing; 2022.Article

- 10. Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an International Study Group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13. ArticlePubMed

- 11. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-13. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Ignacio de Ulibarri J, Gonzalez-Madrono A, de Villar NG, Gonzalez P, Gonzalez B, Mancha A, et al. CONUT: a tool for Controlling Nutritional Status. First validation in a hospital population. Nutr Hosp 2005;20:38-45.Article

- 13. Motoi F, Hata T, Ariake K, Kawaguchi K, Ishida M, Mizuma M, et al. Clinical impact of perioperative malnutrition in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Jpn Soc Parenter Enteral Nutr 2019;1:216-26.Article

- 14. Harris JA, Benedict FG. A biometric study of human basal metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1918;4:370-3. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Perinel J, Mariette C, Dousset B, Sielezneff I, Gainant A, Mabrut JY, et al. Early enteral versus total parenteral nutrition in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: a randomized multicenter controlled trial (Nutri-DPC). Ann Surg 2016;264:731-7. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Cai J, Yang G, Tao Y, Han Y, Lin L, Wang X, et al. A meta-analysis of the effect of early enteral nutrition versus total parenteral nutrition on patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2020;22:20-5. ArticlePubMed

- 17. Takagi K, Domagala P, Hartog H, van Eijck C, Groot Koerkamp B. Current evidence of nutritional therapy in pancreatoduodenectomy: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Gastroenterol Surg 2019;3:620-9. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 18. Bouloubasi Z, Karayiannis D, Pafili Z, Almperti A, Nikolakopoulou K, Lakiotis G, et al. Re-assessing the role of peri-operative nutritional therapy in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing surgery: a narrative review. Nutr Res Rev 2024;37:121-30. ArticlePubMed

, Masahiro Iseki, Shuichiro Hayashi, Aya Noguchi, Hideaki Sato, Shingo Yoshimachi, Akiko Kusaka, Mitsuhiro Shimura, Shuichi Aoki, Daisuke Douchi, Takayuki Miura, Shimpei Maeda, Masamichi Mizuma

, Masahiro Iseki, Shuichiro Hayashi, Aya Noguchi, Hideaki Sato, Shingo Yoshimachi, Akiko Kusaka, Mitsuhiro Shimura, Shuichi Aoki, Daisuke Douchi, Takayuki Miura, Shimpei Maeda, Masamichi Mizuma , Kei Nakagawa

, Kei Nakagawa , Takashi Kamei

, Takashi Kamei , Michiaki Unno

, Michiaki Unno

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

Cite

Cite