Scopus, KCI, KoreaMed

Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Clin Nutr > Volume 9(2); 2017 > Article

- Review Article Nutritional Support for Pediatric Patients with Biliary Atresia

- Joong Kee Youn1,*, Ji-Young Song2,*, Hyun-Young Kim1

- 담도 폐쇄증 환자의 영양 지원

- 윤중기1,*, 송지영2,*, 김현영1

-

Journal of the Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2017;9(2):56-61.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15747/jcn.2017.9.2.56

Published online: December 31, 2017

Department of Pediatric Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

Department of Food Service and Nutrition Care, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- Correspondence to Hyun-Young Kim Department of Pediatric Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 103 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080, Korea Tel: +82-2-2072-2478, Fax: +82-2-766-3975, E-mail: spkhy02@snu.ac.kr

Joong Kee Youn and Ji-Young Song contributed equally to this work.

Copyright: © Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,711 Views

- 11 Download

Abstract

- Biliary atresia (BA) is a major cause of extrahepatic biliary obstruction in children. Malnutrition is a significant clinical problem in children with BA. BA may induce the malabsorption of fat and fat-soluble vitamins, resulting in cholestasis and an impaired nutritional status. For the treatment of BA, it is most important to reconstruct the bile flow as early as possible by performing a Kasai portoenterostomy. After the Kasai operation, growth and nutrition are restored, but to follow normal growth and development, it is necessary to evaluate the nutritional status and support. Therefore, the purpose of nutritional support in children with BA is to normalize growth and development, prevent further liver damage and deterioration of the patient’s nutritional status, avoid vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and improve the quality of life of patients.

서론

본론

1) 영양 지원 시 고려해야 할 사항

2) 열량

Adapted from the article of Baker et al. Pediatr Transplant 2007;11(8):825-34.24

BCAA = branched chain amino acids; MCT = medium-chain triglyceride; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acid; LCP = long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids.

3) 탄수화물

4) 단백질

5) 지방

6) 지용성 비타민

Adapted from The A.S.P.E.N. pediatric nutrition support core curriculum. 2nd ed. Silver Spring:ASPEN;2015:411-26.28

7) 무기질

결론

- 1. Bernstein J, Braylan R, Brough AJ. Bile-plug syndrome: a correctable cause of obstructive jaundice in infants. Pediatrics 1969;43(2):273-6. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 2. Perlmutter DH, Shepherd RW. Extrahepatic biliary atresia: a disease or a phenotype? Hepatology 2002;35(6):1297-304. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 3. Sokol RJ, Mack C, Narkewicz MR, Karrer FM. Pathogenesis and outcome of biliary atresia: current concepts. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2003;37(1):4-21. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Oh JT, Kim DY, Kim SC, Kim IK, Kim HY, Kim HY, et al. Biliary atresia: a survey by the Korean association of pediatric surgeons in 2011. J Korean Assoc Pediatr Surg 2013;19(1):1-13. Article

- 5. Kasai M, Suzuki S. A new operation for “non-correctable” biliary atresia: hepatic porto-enterostomy [in Japanese]. Shujyutsu 1959;13:733-9.Article

- 6. DeRusso PA, Ye W, Shepherd R, Haber BA, Shneider BL, Whitington PF, et al. Growth failure and outcomes in infants with biliary atresia: a report from the Biliary Atresia Research Consortium. Hepatology 2007;46(5):1632-8. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Cowles RA. The jaundiced infant: biliary atresia. In: Coran AG, Adzick NS, Krummel TM, Laberge JM, Shamberger RC, Caldamone AA, editors. Pediatric surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2016. p. 1321-30.Article

- 8. Glasgow JF, Hamilton JR, Sass-Kortsak A. Fat absorption in congenital obstructive liver disease. Arch Dis Child 1973;48(8):601-7. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Barkin RM, Lilly JR. Biliary atresia and the Kasai operation: continuing care. J Pediatr 1980;96(6):1015-9. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Silverberg M, Davidson M. Nutritional requirements of infants and children with liver disease. Am J Clin Nutr 1970;23(5):604-13. ArticlePubMed

- 11. Weber A, Roy CC. The malabsorption associated with chronic liver disease in children. Pediatrics 1972;50(1):73-83. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 12. Handa N, Suita S, Ikeda K, Doki T, Naito K. Requirement of parenteral fat in infants with biliary atresia. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1985;9(6):685-90. ArticlePubMed

- 13. Norman A, Strandvik B, Zetterström R. Bile acid excretion and malabsorption in intrahepatic cholestasis of infancy (” neonatal hepatitis”). Acta Paediatr Scand 1969;58(1):59-72. ArticlePubMed

- 14. Pierro A, Koletzko B, Carnielli V, Superina RA, Roberts EA, Filler RM, et al. Resting energy expenditure is increased in infants and children with extrahepatic biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg 1989;24(6):534-8. ArticlePubMed

- 15. Chin SE, Shepherd RW, Thomas BJ, Cleghorn GJ, Patrick MK, Wilcox JA, et al. Nutritional support in children with end-stage liver disease: a randomized crossover trial of a branched-chain amino acid supplement. Am J Clin Nutr 1992;56(1):158-63. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Holt RI, Miell JP, Jones JS, Mieli-Vergani G, Baker AJ. Nasogastric feeding enhances nutritional status in paediatric liver disease but does not alter circulating levels of IGF-I and IGF binding proteins. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000;52(2):217-24. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 17. Sundaram SS, Mack CL, Feldman AG, Sokol RJ. Biliary atresia: Indications and timing of liver transplantation and optimization of pretransplant care. Liver Transpl 2017;23(1):96-109. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 18. Chongsrisawat V, Ruttanamongkol P, Chaiwatanarat T, Chandrakamol B, Poovorawan Y. Bone density and 25-hydroxyvitamin D level in extrahepatic biliary atresia. Pediatr Surg Int 2001;17(8):604-8. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 19. Katayama H, Suruga K, Kurashige T, Kimoto T. Bone changes in congenital biliary atresia. Radiologic observation of 8 cases. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1975;124(1):107-12. ArticlePubMed

- 20. Ohshima K, Kubo Y, Samejima N. Bone mineral analysis and X-ray examination of the bone in patients with biliary atresia. Jpn J Surg 1990;20(5):537-44. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 21. Glasgow JF, Thomas PS. The osteodystrophy of prolonged obstructive liver disease in childhood. Acta Paediatr Scand 1976;65(1):57-64. ArticlePubMed

- 22. Shepherd RW, Chin SE, Cleghorn GJ, Patrick M, Ong TH, Lynch SV, et al. Malnutrition in children with chronic liver disease accepted for liver transplantation: clinical profile and effect on outcome. J Paediatr Child Health 1991;27(5):295-9. ArticlePubMed

- 23. Mouzaki M, Ng V, Kamath BM, Selzner N, Pencharz P, Ling SC. Enteral energy and macronutrients in end-stage liver disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2014;38(6):673-81. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 24. Baker A, Stevenson R, Dhawan A, Goncalves I, Socha P, Sokal E. Guidelines for nutritional care for infants with cholestatic liver disease before liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant 2007;11(8):825-34. ArticlePubMed

- 25. Buts JP, De Keyser N, Collette E, Bonsignore M, Lambotte L, Desjeux JF, et al. Intestinal transport of calcium in rat biliary cirrhosis. Pediatr Res 1996;40(4):533-41. ArticlePubMed

- 26. Sokal EM, Baudoux MC, Collette E, Hausleithner V, Lambotte L, Buts JP. Branched chain amino acids improve body composition and nitrogen balance in a rat model of extra hepatic biliary atresia. Pediatr Res 1996;40(1):66-71. ArticlePubMed

- 27. Charlton CP, Buchanan E, Holden CE, Preece MA, Green A, Booth IW, et al. Intensive enteral feeding in advanced cirrhosis: reversal of malnutrition without precipitation of hepatic encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child 1992;67(5):603-7. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 28. Kocoshis SA, Wieman RA, Goldschmidt ML. Hepatic disease. In: Corkins MR, Balint J, Bobo E, Plogsted S, Yaworski JA, Kuhn J, editors. The A.S.P.E.N. pediatric nutrition support core curriculum. 2nd ed. Silver Spring: ASPEN; 2015. p. 411-26.Article

- 29. Dewey KG, Beaton G, Fjeld C, Lönnerdal B, Reeds P. Protein requirements of infants and children. Eur J Clin Nutr 1996;50(Suppl 1):S119-47; discussion S147-50.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Socha P, Koletzko B, Swiatkowska E, Pawlowska J, Stolarczyk A, Socha J. Essential fatty acid metabolism in infants with cholestasis. Acta Paediatr 1998;87(3):278-83. ArticlePubMed

- 31. Moukarzel AA, Najm I, Vargas J, McDiarmid SV, Busuttil RW, Ament ME. Effect of nutritional status on outcome of orthotopic liver transplantation in pediatric patients. Transplant Proc 1990;22(4):1560-3. ArticlePubMed

- 32. Shu X, Kang K, Zhong J, Ji S, Zhang Y, Hu H, et al. Meta-analysis of branched chain amino acid-enriched nutrition to improve hepatic function in patients undergoing hepatic operation. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2014;22(1):43-7. ArticlePubMed

- 33. Kaufman SS, Murray ND, Wood RP, Shaw BW Jr, Vanderhoof JA. Nutritional support for the infant with extrahepatic biliary atresia. J Pediatr 1987;110(5):679-86. ArticlePubMed

- 34. Bach A, Schirardin H, Weryha A, Bauer M. Ketogenic response to medium-chain triglyceride load in the rat. J Nutr 1977;107(10):1863-70. ArticlePubMed

- 35. Kaufman SS, Scrivner DJ, Murray ND, Vanderhoof JA, Hart MH, Antonson DL. Influence of portagen and pregestimil on essential fatty acid status in infantile liver disease. Pediatrics 1992;89(1):151-4. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 36. Koletzko B, Agostoni C, Carlson SE, Clandinin T, Hornstra G, Neuringer M, et al. Long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA) and perinatal development. Acta Paediatr 2001;90(4):460-4. ArticlePubMed

- 37. Pettei MJ, Daftary S, Levine JJ. Essential fatty acid deficiency associated with the use of a medium-chain-triglyceride infant formula in pediatric hepatobiliary disease. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;53(5):1217-21. ArticlePubMed

- 38. Beath SV, Johnson S, Willis KD, Kelly DA, Booth IW. 136 Growth and lumenal fatsolubilisation in cholestatic infants on medium chain triglyceride (MCT). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1996;22(4):443.Article

- 39. Lapillonne A, Hakme C, Mamoux V, Chambon M, Fournier V, Chirouze V, et al. Effects of liver transplantation on long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid status in infants with biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000;30(5):528-32. ArticlePubMed

- 40. Saron ML, Godoy HT, Hessel G. Nutritional status of patients with biliary atresia and autoimmune hepatitis related to serum levels of vitamins A, D and E. Arq Gastroenterol 2009;46(1):62-8. ArticlePubMed

- 41. Shneider BL, Magee JC, Bezerra JA, Haber B, Karpen SJ, Raghunathan T, et al. Efficacy of fat-soluble vitamin supplementation in infants with biliary atresia. Pediatrics 2012;130(3):e607-14. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 42. Dong R, Sun S, Liu XZ, Shen Z, Chen G, Zheng S. Fat-soluble vitamin deficiency in pediatric patients with biliary atresia. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2017;doi:10.1155/2017/7496860. ArticlePDF

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

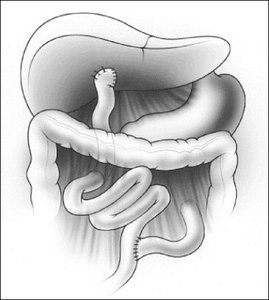

Fig. 1

Macronutrient requirements in cholestatic infants24

| Nutritional element | Daily requirements |

|---|---|

| Energy | Up to 150% of requirements for age |

| Carbohydrate | 40%∼60% energy |

| Protein (g/kg) | 3∼4 (minimum, 2) |

| BCAA | 10% total protein |

| Fat | 30%∼50% energy |

| MCT | 30%∼70% total fat |

| PUFA/LCP | >10% total energy |

Adapted from the article of Baker et al. Pediatr Transplant 2007;11(8):825-34.24

BCAA = branched chain amino acids; MCT = medium-chain triglyceride; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acid; LCP = long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids.

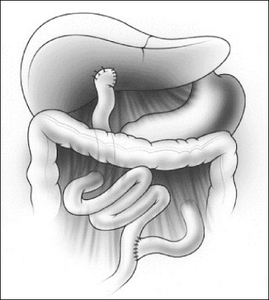

Enteral formula for infants with biliary atresia

| MCT (% of fat) | PUFA (% of energy) | Protein (g/100 mL) | Energy (kcal/100 mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCT Formula (Maeil, Seoul, Korea) | 81 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 60 |

| HA (Maeil, Seoul, Korea) | 22 | 14 | 1.8 | 70 |

| Premie (Maeil, Seoul, Korea) | 37 | 12 | 2.1 | 70 |

| Absolute Step 1 (Maeil, Seoul, Korea) | 12 | 13 | 1.3 | 70 |

| Neocate (Nutricia, Schiphol, The Netherlands) | 5 | 8.1 | 1.95 | 71 |

| Infatrini (Nutricia, Schiphol, The Netherlands) | 16 | 8.6 | 2.6 | 100 |

MCT = medium-chain triglyceride; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acid.

Fat soluble vitamin recommendations for pediatric liver disease28

| Vitamin | Amount |

|---|---|

| Vitamin A | 5,000 IU/d up to a maximum of 25,000 IU/d |

| 25-OH vitamin D | 800∼8,000 IU/d of vitamin D2 or D3 |

| Vitamin E | 20∼25 IU/kg/d as tocopherol polyethylene glycol succinate |

| Vitamin K | 2.5∼5 mg/d 3 times per week |

Adapted from The A.S.P.E.N. pediatric nutrition support core curriculum. 2nd ed. Silver Spring:ASPEN;2015:411-26.28

Fat soluble vitamin supplements

| Amount | Vitamin A (IU) | Vitamin D (IU) | Vitamin E (IU) | Vitamin K (mcg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvityl-I (Youngjin, Seoul, Korea) | 5 mL | 2,500 | 200 | 5 | - |

| Polyvisol with Iron (Meadjohnson, Chicago, IL, USA) | 1 mL | 750 | 400 | 5 | - |

| Centrum Kids (Pfizer, New York, USA) | 2 T | 500 | 400 | 45 | 30 |

Adapted from the article of Baker et al. Pediatr Transplant 2007;11(8):825-34. BCAA = branched chain amino acids; MCT = medium-chain triglyceride; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acid; LCP = long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids.

MCT = medium-chain triglyceride; PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acid.

Adapted from The A.S.P.E.N. pediatric nutrition support core curriculum. 2nd ed. Silver Spring:ASPEN;2015:411-26.

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

Cite

Cite