Scopus, KCI, KoreaMed

Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Ann Clin Nutr Metab > Volume 15(1); 2023 > Article

- Original article Preoperative consumption of a carbohydrate drink before laparoscopic cholecystectomy is safe and beneficial in Korea: a non-randomized controlled study

-

Yoo Jin Choi1,2

, Yoonhyeong Byun1,3

, Yoonhyeong Byun1,3 , Seong Mi Yang4

, Seong Mi Yang4 , Ho-Jin Lee4

, Ho-Jin Lee4 , Hongbeom Kim1,5

, Hongbeom Kim1,5

-

Annals of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism 2023;15(1):15-21.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15747/ACNM.2023.15.1.15

Published online: April 1, 2023

1Department of Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

2Department of Surgery, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

3Department of Surgery, Uijeongbu Eulji Medical Center, Uijeongbu, Korea

4Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

5Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- Corresponding author: Hongbeom Kim, email: hongbeom.kim@samsung.com

© 2023 The Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition · The Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 7,799 Views

- 86 Download

- 1 Crossref

Abstract

-

Purpose Overnight fasting prior to elective surgery is the traditional way of avoiding the risk of aspiration during anesthesia induction. However, it causes mental and metabolic stress to patients. Therefore, we investigated the safety and potential benefits of the preoperative consumption of a carbohydrate drink.

-

Methods This was a single-center prospective, nonrandomized study with questionnaire. Patients scheduled for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy were included. There was no restriction on age, underlying diseases, and biliary drainage prior to surgery. They were preoperatively given either a carbohydrate drink or were instructed to fast from midnight before surgery. Perioperative emotional status was measured using the visual analog scale.

-

Results The 132 patients completed the questionnaire, with 68 receiving the carbohydrate drink and 64 following nil per oral after-midnight instruction. There were no postoperative complications related to preoperative drink consumption or the cholecystectomy procedure itself in both groups. There were no significant differences in all the assessed feelings postoperatively except that preoperative discomforts, such as hunger and thirst, were significantly more alleviated in the group of preoperative consumption of a carbohydrate drink.

-

Conclusion Preoperative consumption of a carbohydrate drink was found to be safe and effective in alleviating preoperative discomfort in elective surgery patients, including older patients and those with underlying comorbidities, who were at greater risk for aspiration. Therefore, we recommend considering preoperative drink consumption as an alternative to traditional overnight fasting in elective surgery patients.

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Supplementary materials

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: YJC, HK. Data curation: YB, SMY. Formal analysis: YJC, HJL. Funding acquisition: HK. Methodology: YJC, YB. Supervision: HJL, HK. Validation: SMY. Writing – original draft: YJC. Writing – review & editing: YJC, HK.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This study was supported by the 2021 Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition Research Grant.

Data availability

Contact the corresponding author for data availability.

| Variable | Total (n=132) | NPO (n=64) | CHOd (n=68) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 57.27±12.95 | 58.06±13.89 | 56.61±12.06 | 0.495 |

| Sex, male | 52 (39.4) | 21 (32.8) | 31 (45.6) | 0.133 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.97±3.96 | 23.87±3.60 | 24.05±4.29 | 0.795 |

| ASA (≥2) | 59 (44.7) | 23 (35.9) | 35 (51.5) | 0.089 |

| HTN | 36 (27.3) | 18 (28.1) | 18 (26.5) | 0.788 |

| DM | 20 (15.2) | 12 (18.8) | 8 (11.8) | 0.247 |

| Other critical diseasea | 41 (31.1) | 15 (23.4) | 25 (36.8) | 0.108 |

| Cancer | 20 (15.2) | 10 (15.6) | 10 (14.7) | 0.853 |

| Past abdominal operative history | 32 (24.2) | 18 (28.1) | 14 (20.6) | 0.389 |

| Preoperative diagnosis | 0.043 | |||

| GB stone | 42 (31.8) | 19 (29.7) | 23 (33.8) | |

| GB polyp | 24 (18.2) | 13 (20.3) | 11 (16.2) | |

| Chronic cholecystitisb | 11 (8.3) | 2 (3.1) | 9 (13.2) | |

| Calculous cholecystitisb | 46 (34.8) | 28 (43.8) | 18 (26.5) | |

| Acute (calculous) cholecystitis | 9 (6.8) | 2 (3.1) | 7 (10.3) | |

| PTGBD | 10 (7.6) | 4 (6.3) | 6 (8.8) | 0.594 |

| ERBD or PTBD | 10 (7.6) | 6 (9.4) | 4 (5.9) | 0.433 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

NPO = nil per oral; CHOd = carbohydrate drink; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes mellitus; GB = gallbladder; PTGBD = percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage; ERBD=endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage; PTBD = percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

aPatients with neurovascular, cardiopulmonary, renal, and hepatic diseases.

bCalculous cholecystitis and chronic cholecystitis had symptoms related GB.

| Variable |

NPO (n=64) |

CHOd (n=68) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | |||

| Anxiety | 3.81±2.24 | 4.41±2.33 | 0.134 |

| Weakness | 3.68±2.21 | 3.07±2.22 | 0.118 |

| Hunger | 3.67±2.50 | 2.79±2.20 | 0.035* |

| Thirst | 4.11±2.44 | 2.78±1.97 | 0.001* |

| Uncomfortable | 3.51±2.25 | 3.21±1.86 | 0.302 |

| Postoperative | |||

| Anxiety | 2.97±2.55 | 3.66±2.37 | 0.109 |

| Weakness | 4.19±2.60 | 3.81±2.49 | 0.392 |

| Hunger | 3.03±2.48 | 3.00±2.33 | 0.940 |

| Thirst | 5.05±2.81 | 4.53±2.67 | 0.281 |

| Uncomfortable | 5.33±2.53 | 5.62±2.29 | 0.501 |

| Nausea | 2.61±2.64 | 2.90±2.45 | 0.526 |

| Pain | 6.13±2.22 | 5.99±2.25 | 0.142 |

- 1. Warner MA, Warner ME, Weber JG. Clinical significance of pulmonary aspiration during the perioperative period. Anesthesiology 1993;78:56-62. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 2. Hausel J, Nygren J, Thorell A, Lagerkranser M, Ljungqvist O. Randomized clinical trial of the effects of oral preoperative carbohydrates on postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2005;92:415-21. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 3. Yildiz H, Gunal SE, Yilmaz G, Yucel S. Oral carbohydrate supplementation reduces preoperative discomfort in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Invest Surg 2013;26:89-95. ArticlePubMed

- 4. Svanfeldt M, Thorell A, Hausel J, Soop M, Rooyackers O, Nygren J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of preoperative oral carbohydrate treatment on postoperative whole-body protein and glucose kinetics. Br J Surg 2007;94:1342-50. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Awad S, Varadhan KK, Ljungqvist O, Lobo DN. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials on preoperative oral carbohydrate treatment in elective surgery. Clin Nutr 2013;32:34-44. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Brady M, Kinn S, Stuart P. Preoperative fasting for adults to prevent perioperative complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;4:CD004423. Article

- 7. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration. Anesthesiology 2017;126:376-93. ArticlePubMed

- 8. Feldheiser A, Aziz O, Baldini G, Cox BP, Fearon KC, Feldman LS, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) for gastrointestinal surgery, part 2: consensus statement for anaesthesia practice. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2016;60:289-334. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 9. Kindler CH, Harms C, Amsler F, Ihde-Scholl T, Scheidegger D. The visual analog scale allows effective measurement of preoperative anxiety and detection of patients' anesthetic concerns. Anesth Analg 2000;90:706-12. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Hausel J, Nygren J, Lagerkranser M, Hellström PM, Hammarqvist F, Almström C, et al. A carbohydrate-rich drink reduces preoperative discomfort in elective surgery patients. Anesth Analg 2001;93:1344-50. ArticlePubMed

- 11. Sada F, Krasniqi A, Hamza A, Gecaj-Gashi A, Bicaj B, Kavaja F. A randomized trial of preoperative oral carbohydrates in abdominal surgery. BMC Anesthesiol 2014;14:93.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth 1997;78:606-17. ArticlePubMed

- 13. Melnyk M, Casey RG, Black P, Koupparis AJ. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols: time to change practice? Can Urol Assoc J 2011;5:342-8. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Nygren J, Thorell A, Jacobsson H, Larsson S, Schnell PO, Hylén L, et al. Preoperative gastric emptying. Effects of anxiety and oral carbohydrate administration. Ann Surg 1995;222:728-34. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Yuill KA, Richardson RA, Davidson HI, Garden OJ, Parks RW. The administration of an oral carbohydrate-containing fluid prior to major elective upper-gastrointestinal surgery preserves skeletal muscle mass postoperatively--a randomised clinical trial. Clin Nutr 2005;24:32-7. ArticlePubMed

- 16. Can MF, Yagci G, Dag B, Ozturk E, Gorgulu S, Simsek A, et al. Preoperative administration of oral carbohydrate-rich solutions: comparison of glucometabolic responses and tolerability between patients with and without insulin resistance. Nutrition 2009;25:72-7. ArticlePubMed

- 17. Madsen M, Brosnan J, Nagy VT. Perioperative thirst: a patient perspective. J Perianesth Nurs 1998;13:225-8. ArticlePubMed

- 18. Boogaerts JG, Vanacker E, Seidel L, Albert A, Bardiau FM. Assessment of postoperative nausea using a visual analogue scale. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2000;44:470-4. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 19. Kindler CH, Harms C, Amsler F, Ihde-Scholl T, Scheidegger D. The visual analog scale allows effective measurement of preoperative anxiety and detection of patients' anesthetic concerns. Anesth Analg 2000;90:706-12. ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

- MODERN CONCEPT OF POSTOPERATIVE ANALGESIA IN PATIENTS UNDERGOING URGENT LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLECYSTECTOMY

O. PYLYPENKO, O. KRAVETS

Pain anesthesia and intensive care.2024; (4(109)): 55. CrossRef

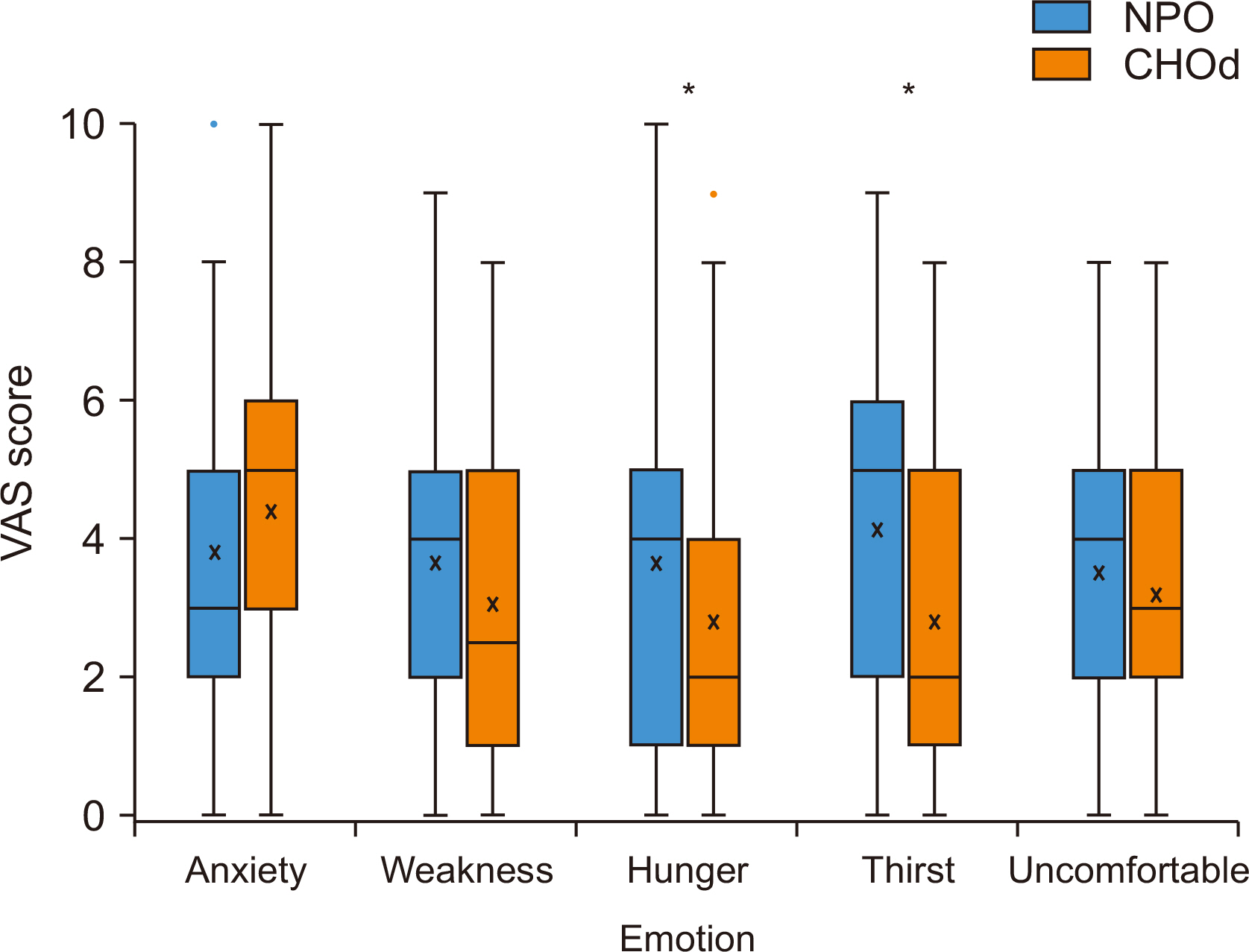

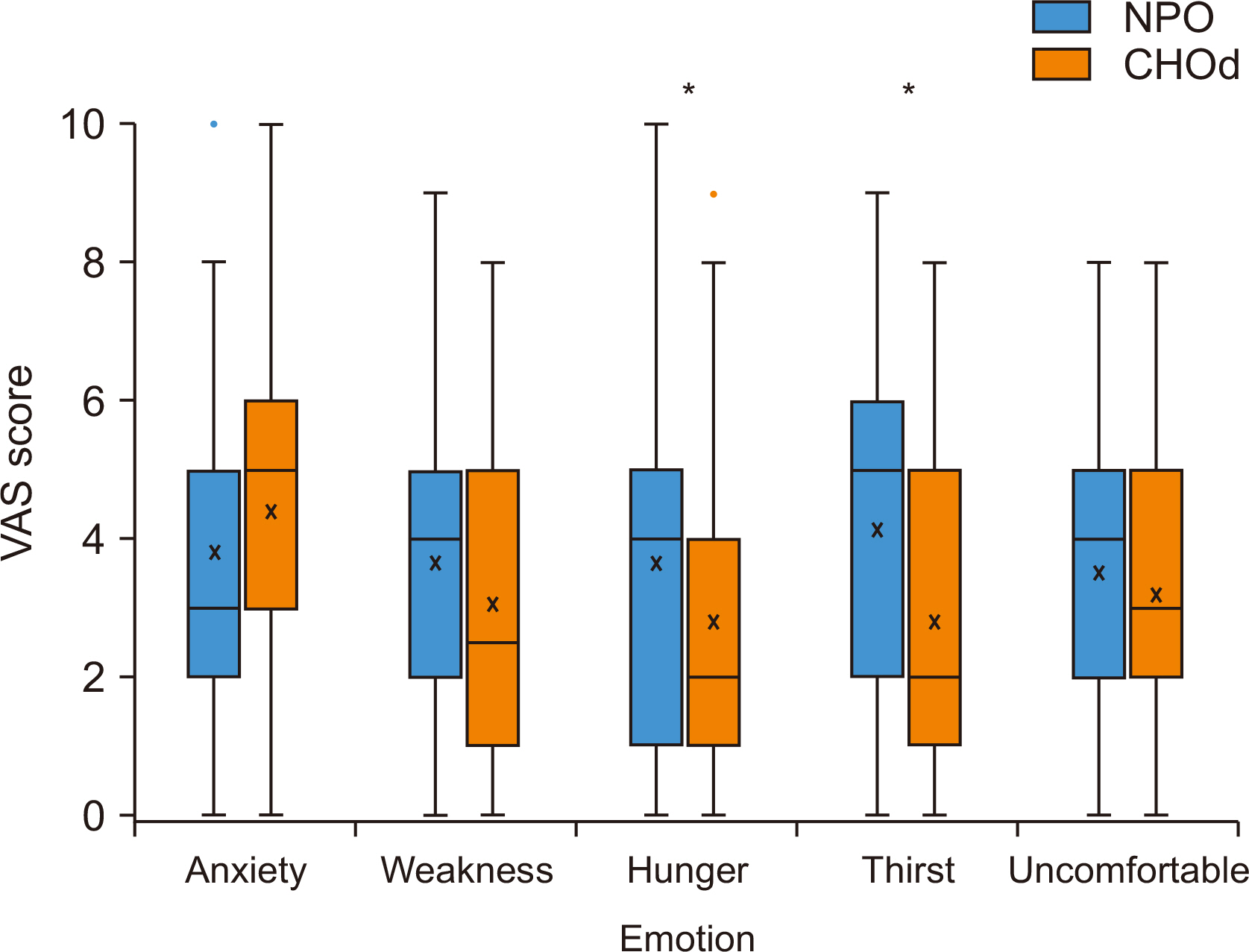

Fig. 1

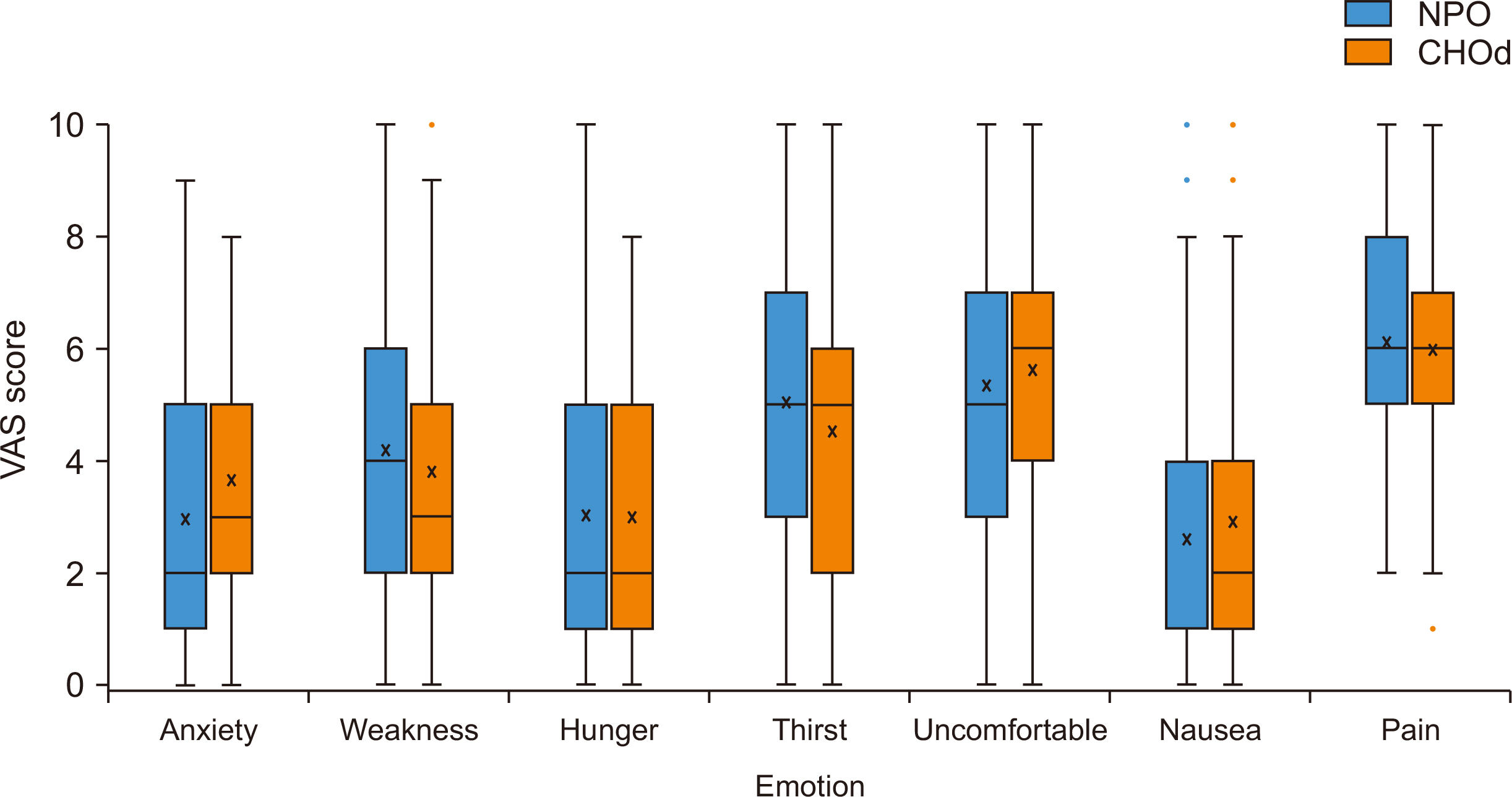

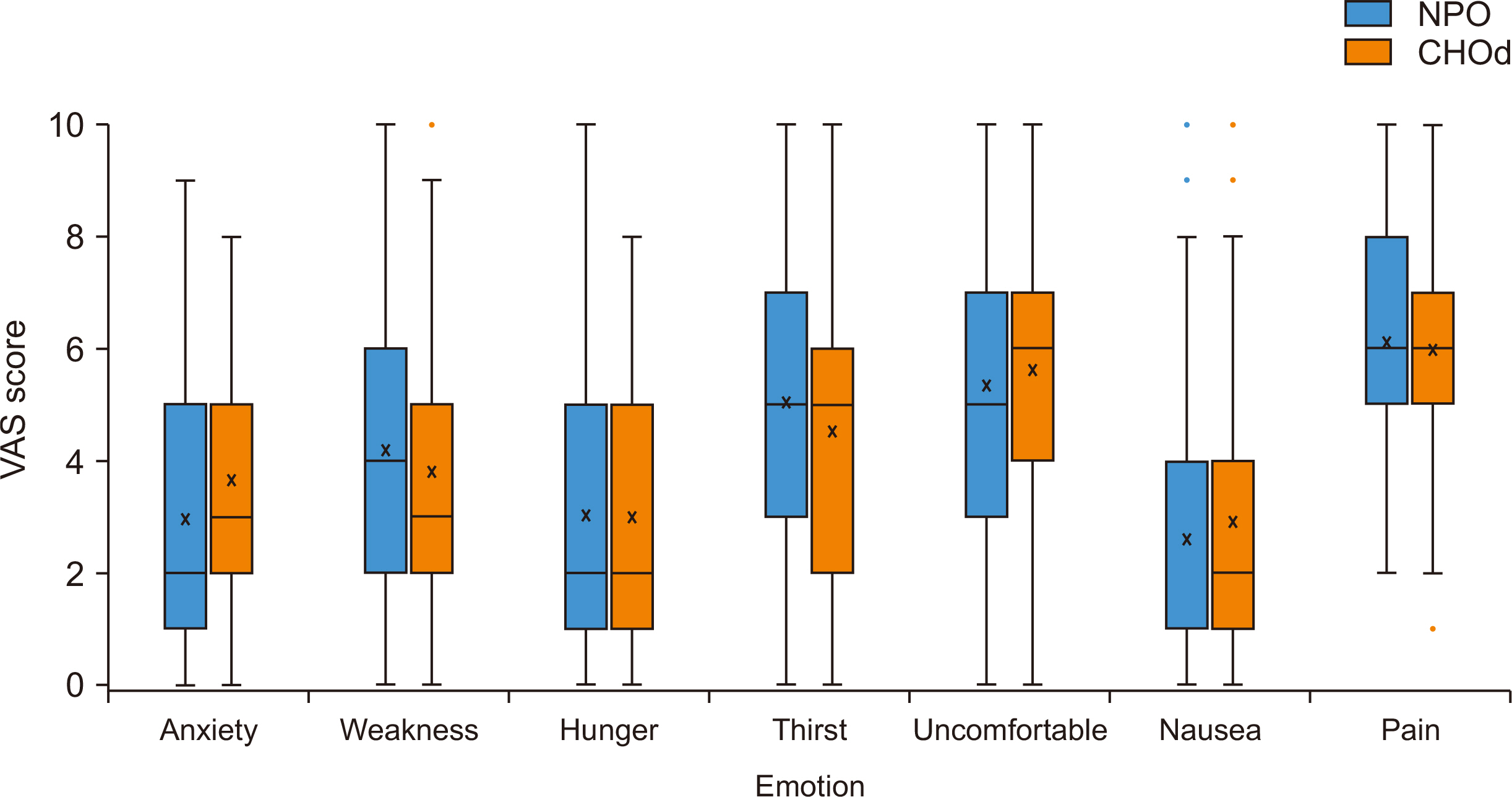

Fig. 2

Preoperative demographics

| Variable | Total (n=132) | NPO (n=64) | CHOd (n=68) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 57.27±12.95 | 58.06±13.89 | 56.61±12.06 | 0.495 |

| Sex, male | 52 (39.4) | 21 (32.8) | 31 (45.6) | 0.133 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.97±3.96 | 23.87±3.60 | 24.05±4.29 | 0.795 |

| ASA (≥2) | 59 (44.7) | 23 (35.9) | 35 (51.5) | 0.089 |

| HTN | 36 (27.3) | 18 (28.1) | 18 (26.5) | 0.788 |

| DM | 20 (15.2) | 12 (18.8) | 8 (11.8) | 0.247 |

| Other critical disease |

41 (31.1) | 15 (23.4) | 25 (36.8) | 0.108 |

| Cancer | 20 (15.2) | 10 (15.6) | 10 (14.7) | 0.853 |

| Past abdominal operative history | 32 (24.2) | 18 (28.1) | 14 (20.6) | 0.389 |

| Preoperative diagnosis | 0.043 | |||

| GB stone | 42 (31.8) | 19 (29.7) | 23 (33.8) | |

| GB polyp | 24 (18.2) | 13 (20.3) | 11 (16.2) | |

| Chronic cholecystitis |

11 (8.3) | 2 (3.1) | 9 (13.2) | |

| Calculous cholecystitis |

46 (34.8) | 28 (43.8) | 18 (26.5) | |

| Acute (calculous) cholecystitis | 9 (6.8) | 2 (3.1) | 7 (10.3) | |

| PTGBD | 10 (7.6) | 4 (6.3) | 6 (8.8) | 0.594 |

| ERBD or PTBD | 10 (7.6) | 6 (9.4) | 4 (5.9) | 0.433 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

NPO = nil per oral; CHOd = carbohydrate drink; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes mellitus; GB = gallbladder; PTGBD = percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage; ERBD=endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage; PTBD = percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

aPatients with neurovascular, cardiopulmonary, renal, and hepatic diseases.

bCalculous cholecystitis and chronic cholecystitis had symptoms related GB.

Operative data

| Variable | NPO (n=64) | CHOd (n=68) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopic/robotic | 59 (92.2)/5 (7.8) | 59 (86.8)/9 (13.2) | 0.327 |

| Gallbladder stones | 45 (70.3) | 49 (72.1) | 0.825 |

| Inflammation (intraoperative) | 28 (43.8) | 28 (41.2) | 0.765 |

| Drain insertion | 9 (14.1) | 17 (25.0) | 0.114 |

Values are presented as number (%).

NPO = nil per oral; CHOd = carbohydrate drink.

Preoperative and postoperative emotional status

| Variable | NPO (n=64) |

CHOd (n=68) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | |||

| Anxiety | 3.81±2.24 | 4.41±2.33 | 0.134 |

| Weakness | 3.68±2.21 | 3.07±2.22 | 0.118 |

| Hunger | 3.67±2.50 | 2.79±2.20 | 0.035 |

| Thirst | 4.11±2.44 | 2.78±1.97 | 0.001 |

| Uncomfortable | 3.51±2.25 | 3.21±1.86 | 0.302 |

| Postoperative | |||

| Anxiety | 2.97±2.55 | 3.66±2.37 | 0.109 |

| Weakness | 4.19±2.60 | 3.81±2.49 | 0.392 |

| Hunger | 3.03±2.48 | 3.00±2.33 | 0.940 |

| Thirst | 5.05±2.81 | 4.53±2.67 | 0.281 |

| Uncomfortable | 5.33±2.53 | 5.62±2.29 | 0.501 |

| Nausea | 2.61±2.64 | 2.90±2.45 | 0.526 |

| Pain | 6.13±2.22 | 5.99±2.25 | 0.142 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

Visual analogue scale was used for measurements.

NPO = nil per oral; CHOd = carbohydrate drink.

*P<0.05.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%). NPO = nil per oral; CHOd = carbohydrate drink; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes mellitus; GB = gallbladder; PTGBD = percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage; ERBD=endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage; PTBD = percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. aPatients with neurovascular, cardiopulmonary, renal, and hepatic diseases. bCalculous cholecystitis and chronic cholecystitis had symptoms related GB.

Values are presented as number (%). NPO = nil per oral; CHOd = carbohydrate drink.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation. Visual analogue scale was used for measurements. NPO = nil per oral; CHOd = carbohydrate drink. *P<0.05.

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN Cite

Cite