Abstract

-

Purpose

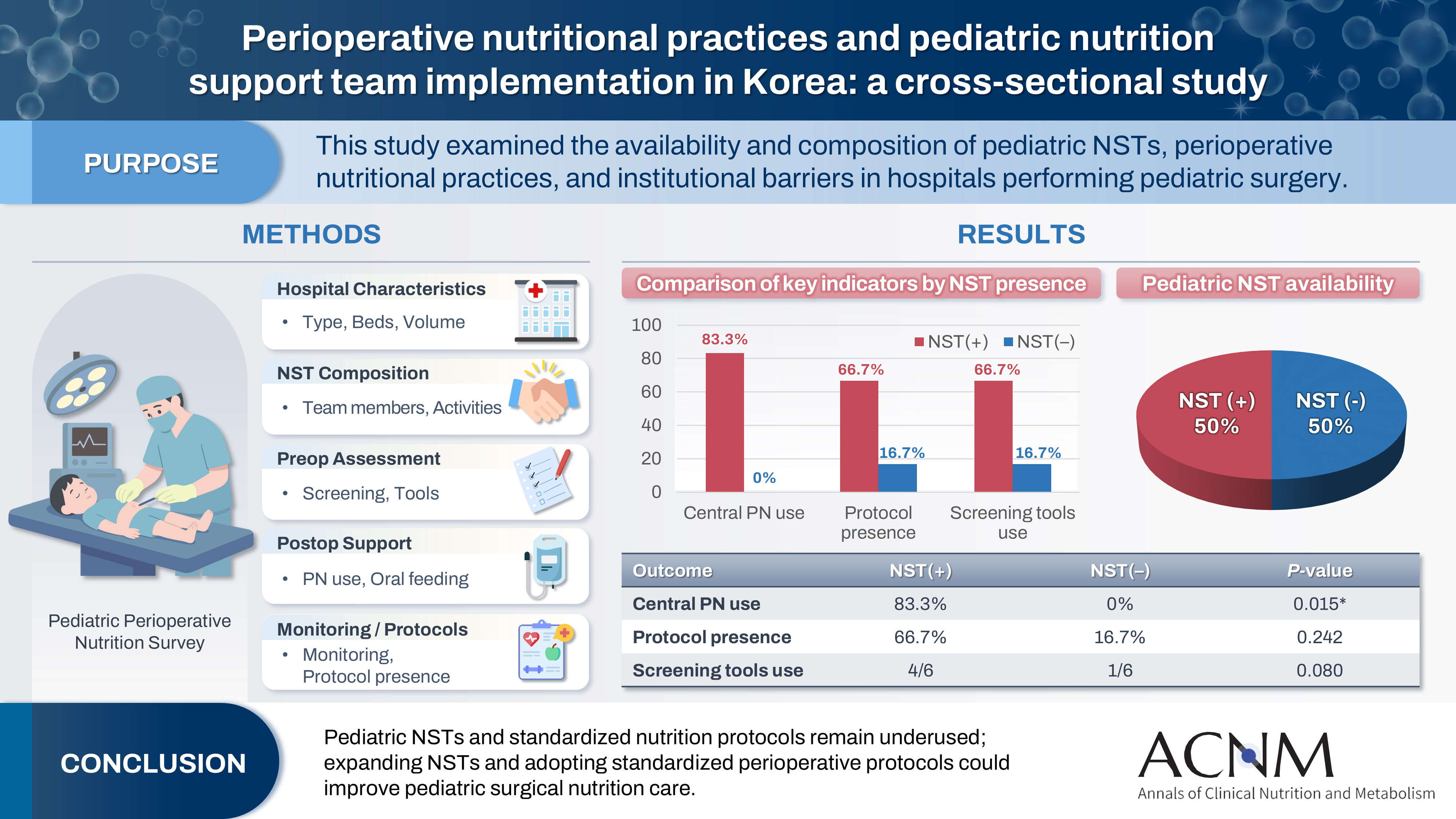

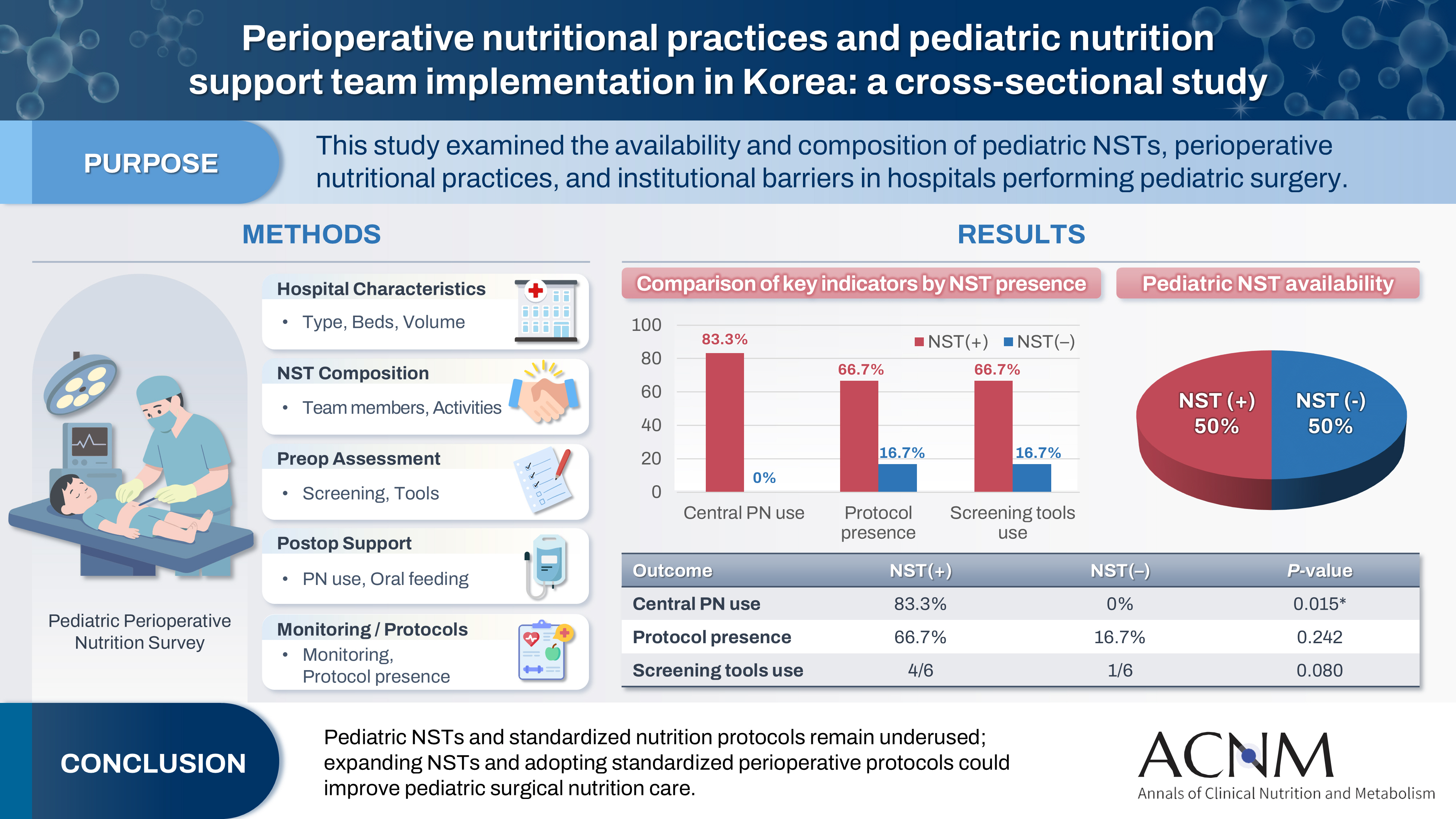

Pediatric surgical patients are vulnerable to perioperative malnutrition, yet standardized nutritional care and structured nutrition support team (NST) involvement remain inconsistent across institutions. Although multidisciplinary nutritional support has gained increasing attention, data on pediatric NST practices within surgical settings in Korea are limited. This study examined the availability and composition of pediatric NSTs, perioperative nutritional practices, and barriers in hospitals performing pediatric surgery.

-

Methods

A nationwide cross-sectional survey was conducted among tertiary and secondary hospitals that perform pediatric surgery in Korea. The questionnaire assessed hospital characteristics, the presence and composition of pediatric NSTs, perioperative nutritional screening and support practices, monitoring protocols.

-

Results

A total of 12 hospitals participated. Although all were high-capacity institutions, only half reported having a pediatric NST. Routine preoperative nutritional screening was performed in 50% of hospitals, and validated tools such as Screening Tool for the Assessment of Malnutrition in Pediatrics (STAMP) and Pediatric Yorkhill Malnutrition Score (PYMS) were used in 41.7%. Hospitals with a pediatric NST more frequently had institutional protocols for nutritional evaluation (66.7% vs. 16.7%) and were more likely to administer central venous parenteral nutrition postoperatively (83.3% vs. 0%, P=0.015). Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocols were implemented in only two hospitals (16.7%). Major barriers to pediatric NST operation included insufficient staffing and time constraints.

-

Conclusion

Pediatric NSTs and standardized perioperative nutrition protocols remain underutilized in Korean surgical centers. Institutions with a pediatric NST demonstrated more structured nutritional practices. Expanding NST infrastructure and establishing standardized perioperative protocols for pediatric surgical patients may enhance the quality and consistency of nutritional care.

-

Keywords: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery; Nutrition assessment; Nutritional support; Parenteral nutrition; Republic of Korea

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Background

Optimal nutritional support is crucial in the perioperative care of pediatric surgical patients, as pre- and postoperative malnutrition is strongly associated with higher rates of postoperative complications, prolonged hospitalization, and impaired wound healing in children undergoing gastrointestinal or congenital anomaly surgery [

1]. Despite this recognized importance, standardized perioperative nutrition protocols and multidisciplinary collaboration remain inconsistently implemented across institutions.

Nutrition support teams (NSTs) have been shown to improve nutrition-related outcomes in pediatric settings. For example, an Iranian study involving neonatal surgical patients with congenital gastrointestinal disorders found that NST implementation significantly enhanced weight gain and caloric intake, while also increasing the rate of enteral feeding [

2]. Similarly, studies conducted in Europe and pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) reported that NSTs improved the timing of enteral nutrition initiation and optimized the delivery of nutrition-focused care [

3].

In Korea, the application of NSTs in general pediatric wards has demonstrated positive outcomes, including increased calorie and protein provision through NST-led consultations [

4]. However, nationwide data in pediatric surgical contexts remain limited. A recent domestic study revealed that although over 30% of hospitalized patients are at risk for malnutrition, only about 4% are referred to NSTs [

5]. These findings underscore a substantial gap between the recognized need for and actual utilization of NST services.

To address this gap, we conducted a cross-sectional nationwide survey of tertiary and secondary hospitals in Korea.

Objectives

This study aimed to assess (1) the presence and structure of pediatric NSTs, (2) perioperative nutritional practices—including parenteral nutrition (PN), oral nutrition advancement, and monitoring—and (3) whether the presence of a dedicated pediatric NST is associated with differences in practice. By comparing postoperative PN utilization, oral nutrition initiation, evaluation protocols, and reimbursement patterns, this study seeks to provide new insights into the organizational and clinical impacts of NST implementation in pediatric surgical care.

Methods

Ethics statement

Institutional review board approval was waived because no identifiable patient data were collected.

Study design

This study was a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based investigation designed to evaluate current nutritional support practices for pediatric surgical patients in Korea.

Setting

The final version of the survey was distributed via an online platform (Google Forms) between March and May 2025. All responses were collected anonymously.

Participants

The survey targeted tertiary and general hospitals in which pediatric surgery is actively performed, defined as university-affiliated hospitals employing full-time pediatric surgeons capable of performing pediatric operations. Pediatric surgeons affiliated with each institution were invited to complete the survey via email and were instructed to submit one response per hospital. A total of 12 out of 20 target hospitals submitted valid responses. No identifiable patient data were collected, and all responses were anonymized.

Variables

The survey included items addressing hospital characteristics, the composition and activities of pediatric NSTs, preoperative nutritional screening and assessment practices, and postoperative nutritional support approaches. These served as the variables analyzed in this study.

Data sources/measurement

The questionnaire was collaboratively developed by pediatric surgeons and clinical nutrition specialists to comprehensively assess nutritional practices in pediatric surgical care. It was designed to capture both structural and practical aspects of perioperative nutritional support across institutions. The survey comprised five key domains: (1) characteristics of participating hospitals, including type of institution, number of pediatric surgical patients, and annual surgical volume; (2) organization and activities of pediatric NSTs, including team composition, rounding practices, designated roles, and reimbursement status; (3) preoperative nutritional screening and assessment practices, including whether screening was routinely performed and what tools or methods were used; (4) postoperative nutritional support strategies, including PN use, approaches to initiating oral feeding, and criteria for assessing nutritional status; and (5) ongoing monitoring practices and the existence of institution-specific protocols for nutritional evaluation and management of pediatric surgical patients.

The questionnaire contained both single-answer and multiple-response items. Before dissemination, it was reviewed and refined based on feedback from two pediatric surgeons to enhance clarity, content validity, and usability. The full survey form is provided in Supplement 1.

Bias

Selection bias may have occurred, as only 12 of the 20 targeted hospitals participated in the survey. The characteristics of the eight non-responding hospitals may differ from those of the responding institutions.

Study size

Since one pediatric surgeon from each of the 12 hospitals responded, no formal sample size estimation was performed.

Statistical methods

Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Comparative analyses were conducted between institutions with and without a dedicated pediatric NST. Associations between NST presence and clinical practices (e.g., frequency of PN use, presence of nutrition protocols) were assessed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Participating hospitals’ characteristics

Demographic information for the pediatric surgeons who completed the survey on behalf of the 12 hospitals was not collected. The responses reflected institutional practices and the current status of pediatric nutritional support and NST implementation rather than personal opinions. The survey was distributed to 20 hospitals, and valid responses were received from 12 institutions, including both tertiary and secondary general hospitals across Korea. Most hospitals reported having more than 500 beds. Seven hospitals (58.3%) performed between 100 and 299 pediatric surgical procedures annually, while two institutions conducted over 1,000 cases per year. A dedicated pediatric NST was present in six of the 12 institutions (50.0%). Hospital characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

Among hospitals with a pediatric NST, the most common team members included pediatricians, nurses, and pharmacists (100.0%) (

Table 2). NST rounds were conducted in 58.3% of institutions, most commonly on a weekly basis. The major responsibilities of pediatric NSTs included nutritional assessment and discussion of interventions for malnourished patients. In five of the 12 centers, NSTs were also involved in providing education for patients and healthcare professionals (

Table 3).

Half of the hospitals (50.0%) reported routinely performing preoperative nutritional screening, while the remaining institutions conducted screening only occasionally or rarely (

Table 4). Common assessment methods included anthropometric measurements (91.7%), dietary intake evaluations (75.0%), and blood tests (66.7%). Validated screening tools such as the Screening Tool for the Assessment of Malnutrition in Pediatrics (STAMP) and the Screening Tool for Risk of Nutritional Status and Growth in Children (STRONGkids) were each used in 41.7% of hospitals. When stratified by NST presence, hospitals with a pediatric NST were more likely to use STAMP and STRONGkids, although the differences were not statistically significant (P=0.080). No significant difference was observed in the overall frequency of nutritional screening (P=0.402).

PN was occasionally or frequently used in most hospitals (

Table 5). Central venous access was significantly more common in hospitals with a pediatric NST compared to those without (83.3% vs. 0.0%, P=0.015). The initiation of oral nutrition in children aged ≥2 years varied, with clear liquid diets being the most common approach (41.7%). Calculation of nutritional requirements was primarily based on kcal/kg/day (58.3%). Weight trends and physical examination findings were the most frequently used indicators of postoperative nutritional status. The presence of a pediatric NST was not associated with significant differences in the timing of oral nutrition initiation (P=0.753) or in the use of nutritional indicators (P=0.261).

Only 41.7% of institutions reported having established protocols for nutritional evaluation and intervention, indicating a lack of standardization in perioperative nutritional care. Although hospitals with pediatric NSTs more frequently reported having such protocols (66.7% vs. 16.7%), the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.242).

Discussion

Key results

Twelve hospitals participated in the survey, six of which had dedicated pediatric NSTs. These NSTs typically comprised pediatricians, surgeons, nurses, pharmacists, and dietitians, and they conducted weekly rounds focused on nutritional assessment and intervention. Half of the hospitals routinely performed preoperative nutritional screening using anthropometric measurements, dietary evaluations, and blood tests. Validated tools such as STAMP and STRONGkids were utilized in 41.7% of institutions. PN was commonly administered postoperatively, with central venous access significantly more frequent in NST-equipped hospitals (83.3% vs. 0.0%, P=0.015). Only 41.7% of hospitals had established nutritional protocols. Institutions with NSTs demonstrated trends toward improved screening practices and protocol adoption, although the differences were not statistically significant.

Interpretation/comparison with previous studies

This nationwide survey is the first to investigate perioperative nutritional practices for pediatric surgical patients in Korea, focusing on the presence and structure of pediatric NSTs. Although the study included tertiary and secondary hospitals—most with more than 500 beds—only 50% had an established pediatric NST. This finding underscores a major opportunity to strengthen institutional frameworks for nutritional care.

Marked variability was observed among institutions regarding nutritional screening, monitoring, and postoperative PN practices. Notably, hospitals with pediatric NSTs showed significantly greater use of central venous PN (83.3% vs. 0.0%, P=0.015) and a trend toward more frequent PN utilization overall (P=0.083), suggesting a more proactive approach to perioperative nutrition. Pediatric NSTs face distinct challenges, including the limited availability of pediatric-specific PN formulations for children under 2 years, differences in institutional compounding capacity, and shortages of personnel dedicated to pediatric nutrition management.

The presence of a pediatric NST was also associated with higher utilization of validated screening tools such as STAMP and STRONGkids, as well as a greater likelihood of having formal nutrition protocols, although these trends did not reach statistical significance. This aligns with prior evidence showing that multidisciplinary NSTs enhance the use of standardized nutrition screening tools. For instance, one PICU study reported that NST implementation increased the use of STAMP and STRONGkids from approximately 40% to over 80% (P<0.01). Similarly, a European systematic survey of 111 PICUs found substantially higher adoption rates (75%–90%) of validated screening tools in NST-equipped units compared to much lower rates (30%–50%) in units without NSTs [

6,

7]. Collectively, these findings support that pediatric NSTs facilitate more systematic and consistent nutritional risk screening.

In adult populations, national surveys have examined NST structure and performance, demonstrating associations with improved clinical outcomes and stronger adherence to nutritional guidelines [

8]. However, comparable data for pediatric surgical populations—particularly in Korea—remain limited. The present study addresses this gap by characterizing current practices in large-capacity hospitals. Although all participating hospitals were tertiary or secondary institutions with over 500 beds, only half reported having a dedicated pediatric NST. Importantly, hospitals with an NST were more likely to have formal institutional protocols for perioperative nutritional evaluation and intervention (66.7% vs. 16.7%), suggesting that NST presence may promote the systematization and standardization of nutritional care processes.

Regarding Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols, only two of the 12 hospitals (16.7%) reported selective implementation for pediatric patients. ERAS represents a multidisciplinary, evidence-based approach to perioperative care designed to accelerate recovery by incorporating elements such as preoperative nutritional assessment, reduced fasting duration, early enteral feeding, and mitigation of surgical stress and catabolism [

9,

10]. Nutritional optimization forms a central component of ERAS, especially for pediatric patients, who are more susceptible to perioperative metabolic imbalance due to higher energy demands and limited reserves. Compared with the limited uptake observed in pediatric practice, ERAS has been far more widely adopted in adult surgery. For instance, a nationwide Italian survey reported that 50.6% of gastric surgeons routinely applied ERAS principles to gastrectomy, and that structured ERAS programs were present in approximately 65% of surgical centers [

11]. For pediatric populations, expert recommendations similarly emphasize preoperative nutritional optimization, fasting minimization, carbohydrate loading, and early postoperative enteral feeding, yet real-world implementation remains scarce [

12]. This disparity highlights a significant gap in the standardization of perioperative nutritional care between adult and pediatric surgical disciplines.

Qualitative feedback from respondents also offered insight into barriers to NST implementation. Among all participants, seven hospitals cited inadequate personnel—particularly a lack of pediatric-dedicated pharmacists and dietitians—while one noted time constraints related to clinical workload, and another cited insufficient professional training in pediatric nutrition. These findings suggest that implementation barriers are not solely infrastructural but also stem from limitations in human resources and specialized expertise.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The sample size was small (n=12), and although institutions were nationally distributed, findings may not be generalizable to all hospital types. Because data were obtained from a single respondent per institution, response bias cannot be excluded. Furthermore, this study did not assess clinical outcomes such as length of stay, infection rates, or growth parameters, which should be incorporated into future analyses.

Suggestion for further studies

To better define the clinical impact of pediatric NSTs, future prospective multicenter studies should include objective patient outcomes. In addition, qualitative investigations into barriers to NST implementation and protocol adherence could inform national strategies for improving perioperative nutritional care in pediatric surgery.

Conclusion

In summary, despite sufficient institutional capacity, the integration of pediatric NSTs and standardized perioperative nutritional care remains limited in Korea. To optimize outcomes for pediatric surgical patients, future efforts should prioritize establishing dedicated pediatric NSTs, fostering multidisciplinary collaboration, and expanding institutional resources and professional training.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: all authors. Data curation: DK, HH. Formal analysis: DK, HYK. Funding acquisition: DK, HH, JKY, HYK. Writing–original draft: DK. Writing–review & editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition (KSSMN).

Data availability

Contact the corresponding author for research data availability.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank all survey participants for their time and contribution to this national study.

Supplementary materials

Table 1.Characteristics of respondent hospitals

|

Variable |

No. (%) |

|

Hospital type |

|

|

Tertiary hospital |

11 (91.7) |

|

Secondary hospital |

1 (8.3) |

|

Number of beds |

|

|

≥1,000 beds |

6 (50.0) |

|

500–999 beds |

6 (50.0) |

|

Pediatric inpatients per day |

|

|

<10 |

2 (16.7) |

|

10–30 |

3 (25.0) |

|

>30 |

2 (16.7) |

|

Not specified |

5 (41.6) |

|

Annual number of pediatric operations |

|

|

<100 |

2 (16.7) |

|

100–299 |

7 (58.3) |

|

300–499 |

0 |

|

500–999 |

1 (8.3) |

|

≥1,000 |

2 (16.7) |

|

Years of pediatric surgery experience |

|

|

<5 yr |

2 (16.7) |

|

5–9 yr |

1 (8.3) |

|

10–14 yr |

2 (16.7) |

|

15–19 yr |

2 (16.7) |

|

≥20 yr |

5 (41.7) |

|

Dedicated pediatric NST |

|

|

Yes |

6 (50.0) |

|

No |

6 (50.0) |

Table 2.Composition of pediatric nutrition support teams

|

Hospital |

Pediatric surgeon |

Pediatrician |

Nurse |

Pharmacist |

Dietitian |

|

Dedicated |

Shared |

Dedicated |

Shared |

Dedicated |

Shared |

|

1 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

2 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

3 |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

4 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

5 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

|

6 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

Table 3.Activities of pediatric nutrition support teams

|

Variable |

No. (%) |

|

Pediatric NST member composition (n=6)a

|

|

|

Pediatric surgeon |

5 (83.3) |

|

Pediatrician |

6 (100.0) |

|

Nurse (dedicated or shared) |

6 (100.0) |

|

Dietitian |

6 (100.0) |

|

Pharmacist |

6 (100.0) |

|

NST rounding implementation (n=12) |

|

|

Performed |

8 (66.7) |

|

Not performed |

2 (16.7) |

|

Not sure |

2 (16.7) |

|

Frequency of rounding (n=12) |

|

|

2–3 times/wk |

2 (16.7) |

|

Weekly |

4 (33.3) |

|

Monthly |

1 (8.3) |

|

No response |

5 (41.7) |

|

Main roles of pediatric NST (n=12)a

|

|

|

Nutritional assessment |

9 (75.0) |

|

Planning and adjusting nutritional intervention |

7 (58.3) |

|

Monitoring of nutritional status |

8 (66.7) |

|

Education of patients and healthcare professionals |

2 (16.7) |

|

Reimbursement of nutritional care |

9 (75.0) |

|

Not sure |

3 (24.9) |

Table 4.Preoperative nutritional screening and assessment practices

|

Variable |

Total, No. (%) |

Pediatric NST (+) |

Pediatric NST (–) |

P-value |

|

Preoperative nutritional screening |

|

|

|

0.402 |

|

Routinely performed |

6 (50.0) |

3 |

3 |

|

|

Occasionally performed |

2 (16.7) |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Rarely performed |

2 (16.7) |

0 |

2 |

|

|

Not performed |

1 (8.3) |

1 |

0 |

|

|

No response |

1 (8.3) |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Assessment tools and methods useda

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anthropometric measurements |

11 (91.7) |

5 |

6 |

0.455 |

|

Dietary intake assessment |

9 (75.0) |

5 |

4 |

0.080 |

|

Blood tests |

8 (66.7) |

3 |

5 |

0.080 |

|

STAMP, STRONGkids |

5 (41.7) |

4 |

1 |

0.080 |

Table 5.Postoperative nutritional support practices

|

Variable |

Total |

Pediatric NST (+) |

Pediatric NST (–) |

P-value |

|

Frequency of parenteral nutrition use |

|

|

|

0.083 |

|

Occasionally used |

6 |

2 |

4 |

|

|

Frequently used |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

|

Rarely used |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

|

Case-by-case decision |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

Route of parenteral nutrition |

|

|

|

0.015 |

|

Central venous |

5 |

5 |

0 |

|

|

Case-dependent |

7 |

1 |

6 |

|

|

Type of oral nutrition started (≥2 yr) |

|

|

|

0.753 |

|

Clear liquids (SFD) |

5 |

3 |

2 |

|

|

Regular diet immediately |

3 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Liquid/puree diet |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Case-by-case decision |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

No response |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Postoperative nutritional monitoring period |

|

|

|

0.382 |

|

Not done |

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

|

Once a week |

6 |

3 |

3 |

|

|

2–3 times/week |

4 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

Presence of nutritional assessment protocol for perioperative children |

|

|

|

0.242 |

|

Yes |

6 |

4 |

2 |

|

|

No |

6 |

1 |

5 |

|

References

- 1. Joosten KF, Hulst JM. Prevalence of malnutrition in pediatric hospital patients. Curr Opin Pediatr 2008;20:590-6. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 2. Zarei-Shargh P, Yuzbashian E, Mehdizadeh-Hakkak A, Khorasanchi Z, Norouzy A, Khademi G, et al. Impact of nutrition support team on postoperative nutritional status and outcome of patients with congenital gastrointestinal anomalies. Middle East J Dig Dis 2020;12:116-22. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 3. Mehta NM, Skillman HE, Irving SY, Coss-Bu JA, Vermilyea S, Farrington EA, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the pediatric critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2017;41:706-42. Article

- 4. Baek S, Rho J, Namgung HW, Lee E, Lee E, Yang HR. The influence of pediatric nutrition support team on hospitalized pediatric patients receiving parenteral nutrition. J Clin Nutr 2020;12:7-13. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 5. Lee YM, Ryoo E, Hong J, Kang B, Choe BH, Seo JH, et al. Nationwide "Pediatric Nutrition Day" survey on the nutritional status of hospitalized children in South Korea. Nutr Res Pract 2021;15:213-24. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 6. Kiss CM, Byham-Gray L, Denmark R, Loetscher R, Brody RA. The impact of implementation of a nutrition support algorithm on nutrition care outcomes in an intensive care unit. Nutr Clin Pract 2012;27:793-801. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 7. van der Kuip M, Oosterveld MJ, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, de Meer K, Lafeber HN, Gemke RJ. Nutritional support in 111 pediatric intensive care units: a European survey. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:1807-13. ArticlePDF

- 8. Nam SH. Current practices and challenges in nutrition support team activities, 2025 in Korea: a multicenter cross-sectional descriptive study. Ann Clin Nutr Metab 2025;17:97-103. ArticlePubMed

- 9. Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, Higashiguchi T, Hubner M, Klek S, et al. ESPEN guideline: clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin Nutr 2017;36:623-50. ArticlePubMed

- 10. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: a review. JAMA Surg 2017;152:292-8. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 11. Romario UF, Ascari F, De Pascale S; GIRCG. Implementation of the ERAS program in gastric surgery: a nationwide survey in Italy. Updates Surg 2023;75:141-8. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Rafeeqi T, Pearson EG. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in children. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6:46.ArticlePubMedPMC

, Honam Hwang2

, Honam Hwang2 , Hee-Beom Yang2

, Hee-Beom Yang2 , Joong Kee Youn1

, Joong Kee Youn1 , Hyun-Young Kim1,3

, Hyun-Young Kim1,3

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

Cite

Cite