Abstract

-

Purpose

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols advocate reduced fasting and early nutrition to improve recovery in surgical patients. However, data on ERAS implementation among Korean surgeons performing major abdominal surgeries remain sparse.

-

Methods

A survey conducted by the External Relation Committee of the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition assessed perioperative nutritional practices among 389 Korean general surgeons from February to September 2023. The survey covered preoperative fasting, carbohydrate drinks, nasogastric tube use, postoperative dietary progression, parenteral nutrition (PN), and oral supplements, yielding 551 responses stratified by specialty.

-

Results

More than 80% of respondents practiced “midnight NPO (Nil Per Os)” fasting, often at the anesthesiology department’s request, while 70%–80% reported no use of preoperative carbohydrate drinks. Most surgeons began dietary progression with water on postoperative day one, advancing to a liquid or soft diet by day two. PN was routinely prescribed by 49% of respondents, with a common dosage of 1,000–1,500 kcal/d. Oral supplements were selectively provided, with 21% of surgeons prescribing them universally.

-

Conclusion

The results reveal significant variability in perioperative nutrition practices across Korean surgical specialties, with many adhering to traditional practices despite ERAS guidelines. These findings highlight a need for standardized guidelines in Korea to optimize perioperative nutritional support and improve patient recovery outcomes following major abdominal surgeries.

-

Keywords: Enhanced recovery after surgery; Enteral nutrition; General surgery; Parenteral nutrition; Surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

Background

Abdominal surgeries often involve direct resection and anastomosis of the gastrointestinal tract, leading to the historical practice of prolonged fasting before and after surgery. Traditionally, extensive preoperative fasting was performed to empty the gastrointestinal tract for safe anesthesia [

1], and postoperative fasting continued until gastrointestinal motility sufficiently recovered and the risk of complications, such as anastomotic leakage, decreased [

2].

However, recent studies have shown that adequate oral nutrition before and after surgery plays a crucial role in patient recovery and outcomes [

3,

4]. As a result, nearly all surgical disciplines are increasingly emphasizing reduced fasting periods as part of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols [

5]. Although many studies from other countries have examined the implementation of reduced preoperative and postoperative fasting times in clinical practice, findings indicate that these practices have not been widely adopted [

6,

7]. Although many general surgeons and surgical oncologists performing major abdominal surgery in Korea strive to follow ERAS guidelines [

8-

11], data on the extent to which Korean surgeons implement ERAS protocols for perioperative nutrition remain limited [

12].

To address this gap, the External Relations Committee of the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition conducted a survey to assess the current clinical perioperative nutritional care among general surgeons performing major abdominal surgeries, including cancer surgeries, in Korea.

Objectives

The survey aimed to understand the variety of protocols employed by surgeons, focusing on perioperative oral and parenteral nutrition (PN) support. Additionally, the study sought to capture the variations in ERAS protocol implementation based on surgery type and individual preferences, as well as to identify the challenges surgeons face when incorporating early perioperative nutrition in clinical practice.

Our committee anticipates that the results of this survey will serve as foundational data for standardizing perioperative nutritional support practices and developing evidence-based clinical guidelines in Korea. Moreover, these findings are expected to provide valuable insights into the optimal timing of pre- and postoperative oral intake, PN, formalization of perioperative nutrition strategies, and integration of perioperative nutritional support into comprehensive surgical care protocols.

Methods

Ethics statement

It is an anonymous survey of which targets are general surgeons in Korea. Therefore, the approval by the institutional review board is not required. Informed consent was obtained from participants.

Study design

Setting

The survey was administered via Google Forms, with a link sent directly to each participant’s mobile device. The survey period extended for seven months, from February to September 2023. Each surgeon was instructed to complete the survey for only one surgical specialty and specific surgical procedure per submission. After completing the survey, they were allowed to participate in additional surveys for other specialties or specific procedures. The following surgical categories were considered:

- Gastric cancer surgery: distal gastrectomy/pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (DG/PPG)

- Gastric cancer surgery: total gastrectomy/proximal gastrectomy (TG/PG)

- Colorectal cancer surgery: colectomy

- Colorectal cancer surgery: low anterior resection/laparoscopic abdominal transanal proctocolectomy with coloanal anastomosis (LAR/LATA) (±ileostomy)

- Hepatobiliary cancer surgery: hepatectomy (±hepaticojejunostomy)

- Hepatobiliary cancer surgery: distal pancreatectomy

- Hepatobiliary cancer surgery: pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s operation, pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy [PPPD], pylorus-resecting pancreaticoduodenectomy [PRPD])

- Metabolic and bariatric surgery: sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass

Participants

The survey targeted general surgeons in Korea who per- form major abdominal surgeries, including cancer surgeries.

The questionnaire was distributed to [475] surgeons through contacts (phone numbers) registered in the database of the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition. There was no exclusion.

Variables

Outcome variables were items of questionnaire.

Bias

Since only voluntary particpants’ responses were included, there may be selection bias.

Data sources/measurements

Data were collected from the response by participants.

Questionnaire structure and content

The questionnaire consisted of six main categories:

1. Preoperative fasting protocols

2. Provision of preoperative carbohydrate-rich drinks

3. Use of preoperative nasogastric (NG) tubes

4. Postoperative dietary progression

5. Postoperative administration of PN

6. Postoperative provision of oral nutritional supplements (ONS)

As shown in

Supplement 1, each category included specific evidence-based questions to capture detailed clinical practice information. For example, surgeons who indicated the use of preoperative fasting (Category 1) were asked to specify the fasting duration (nothing by mouth or Nil Per Os [NPO]), choosing from the following options: 12 hours, 6 hours, or 2 hours prior to surgery. Respondents also had the option to select “Other” and specify a fasting duration not included in the predefined options. During data analysis, many respondents who selected “Other” indicated a fasting duration of 24 hours. To reflect this finding, 24 hours was included as a separate category during analysis. It was clarified that fasting included drinking water. Those who selected 12 hours prior (i.e., midnight NPO [MNNPO] one day before surgery) were further asked to explain their rationale.

In Category 3, where respondents were queried on the use of NG tubes, questions explored the timing of NG tube insertion and removal.

In Category 4, which addressed postoperative dietary progression, respondents were asked to specify the timing of initial oral fluid intake (e.g., sips of water, SOW) and solid food intake (e.g., liquid or soft diet) on specific postoperative days (PODs), including the day of surgery (POD 0), POD 1, POD 2, and subsequent days. Additionally, they were asked about the specific type of initial solid food provided. Examples include a liquid diet (such as finished product or rice gruel), a soft diet (such as soup or rice porridge), or a regular diet (such as rice).

Category 5 addressed postoperative PN administration, inquiring whether it was prescribed universally or selectively. Surgeons were asked about the types of PN commonly used (e.g., all-in-one solution, two-in-one solution, amino acid solutions, lipid emulsions), the total daily caloric intake provided (<500, 500–<1,000, 1,000–<1,500, 1,500–<2,000, or ≥2,000 kcal), and the duration of administration (e.g., 1, 2, ≥6 days). For selective administration, respondents were further asked to specify criteria, such as poor preoperative nutritional status, inadequate postoperative oral intake, or the need for fasting due to postoperative complications.

Similarly, Category 6 examined the use of postoperative ONS, asking if they were provided to all patients or selectively. Questions in this section covered the types of supplements used (e.g., standard formulas, immunomodulating formulas, high-protein formulas, nutrient-dense formulas, elemental or semi-elemental formulas), the total volume provided per day (200, 400, 600, 800, or ≥1,000 mL), and the duration of administration (during hospitalization only or continued after discharge). Selective administration criteria included factors like poor preoperative nutritional status or inadequate postoperative oral intake. Items of questionnaire are available at

Supplement 1.

Since all target society members were invited and only responses from voluntary participants were included, no sample size estimation was performed.

Statistical methods

Responses were analyzed in aggregate and stratified by specialty to examine trends across surgical fields. Descriptive statistics were applied.

Results

Participant demographics and survey response rates

A total of 389 surgeons participated in the survey, allowing multiple answers per surgical specialty per respondent, resulting in a total of 551 completed questionnaires. Gastric cancer surgeons (n=149) were the most responsive group, followed by surgeons specializing in colorectal, hepatobiliary, and bariatric/metabolic surgery. When broken down into specific procedures, DG and PPG had the highest response rates (

Table 1).

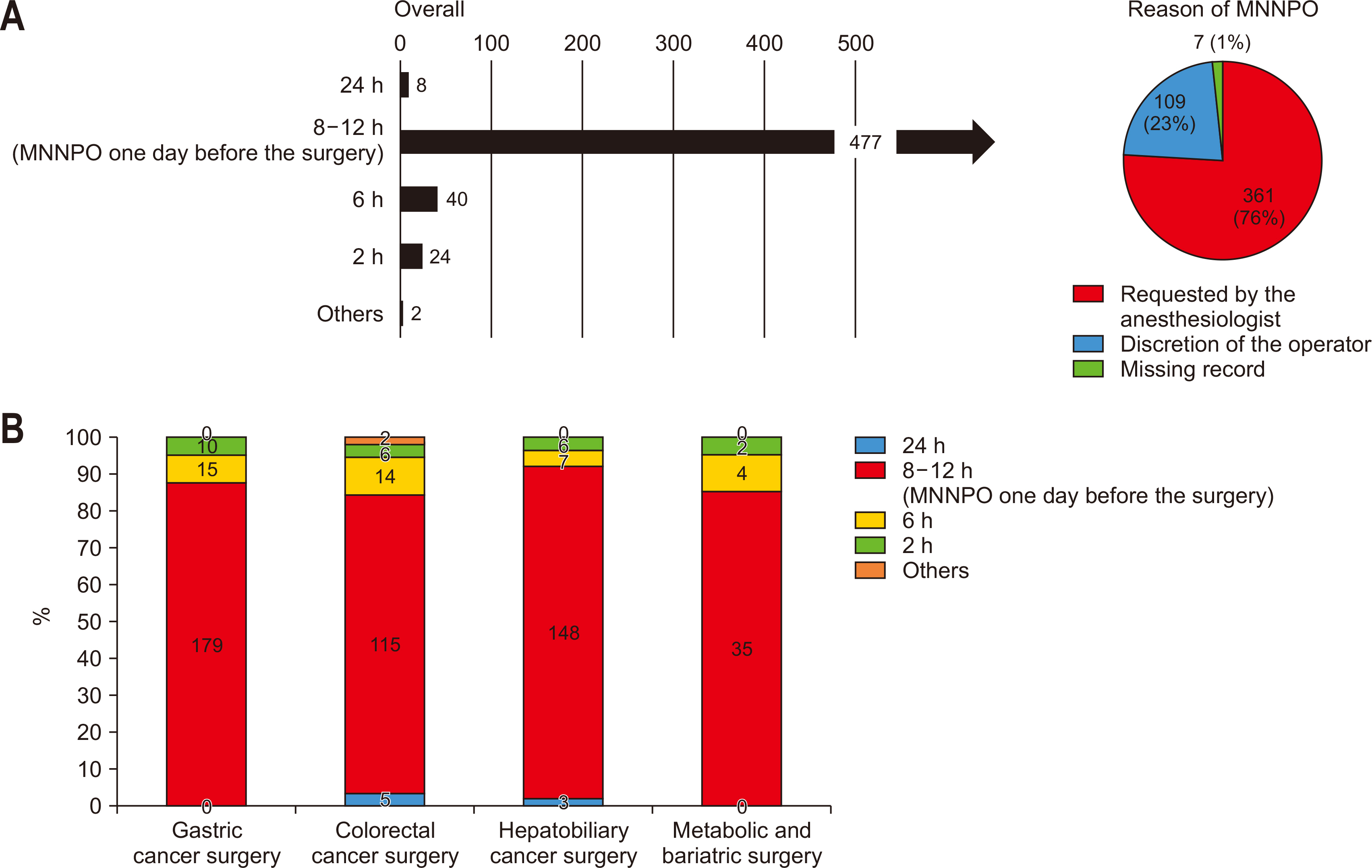

Most participants reported a fasting protocol, instructing patients to abstain from food and drink starting at midnight the day of surgery. This practice was predominantly driven by anesthesiology department requirements (

Fig. 1A). Analysis by specialty revealed that over 80% of respondents across all specialties enforced this preoperative fasting protocol (

Fig. 1B).

Approximately 80% of respondents did not administer carbohydrate-rich drinks before surgery, with similar results across specialties (70%–80%) (

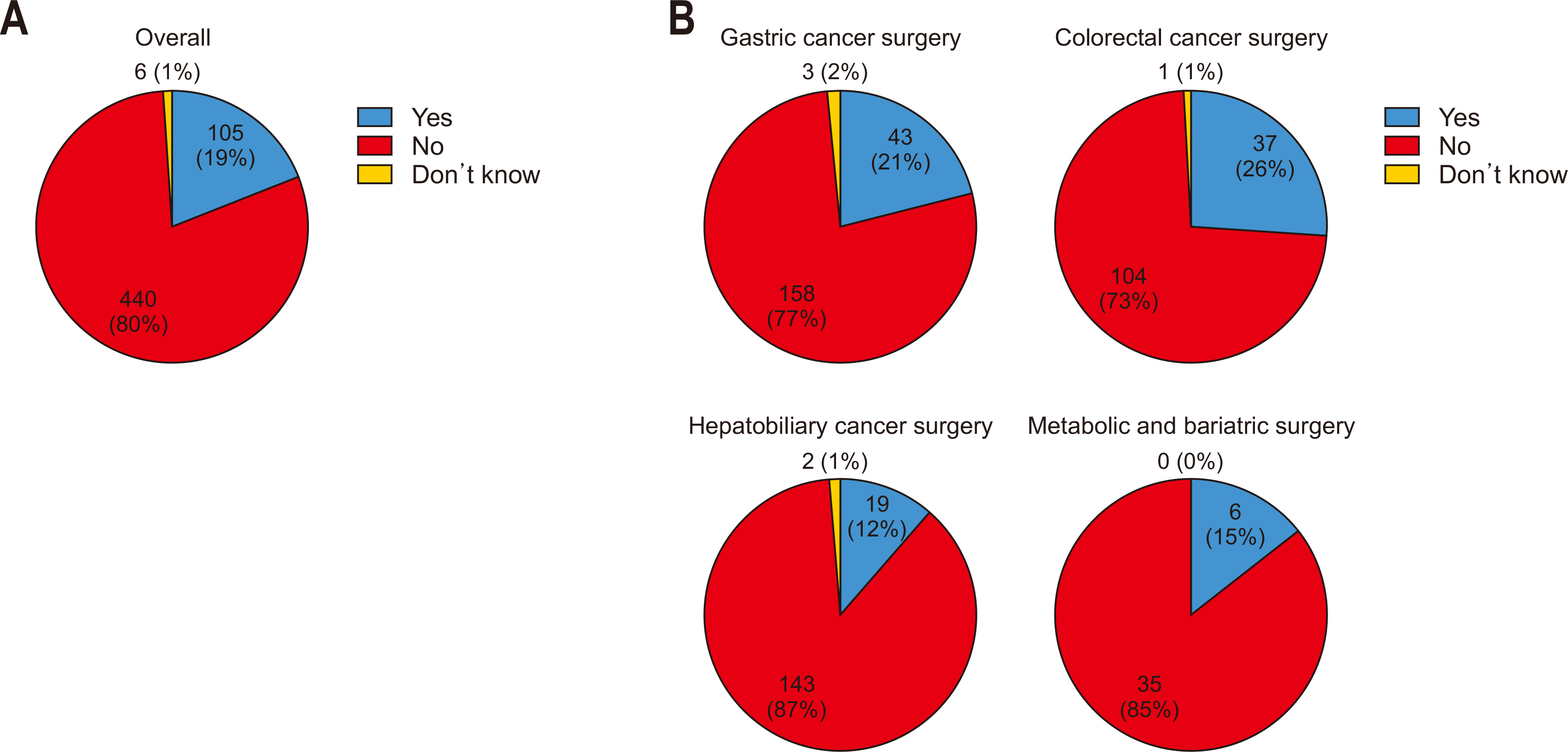

Fig. 2).

Only 30% of all respondents reported NG tube insertion before surgery, while 70% indicated no preoperative insertion. For preoperative placement of NG tubes, the most common timing was during the interval after induction of anesthesia but prior to the start of surgery. The removal of NG tubes most frequently occurred on POD 1 (

Fig. 3A). When analyzed by specialty, the rate of preoperative NG tube insertion was higher in hepatobiliary cancer surgeries (57%) compared to other specialties, although the overall trend remained consistent across most fields. Similar to the overall findings, NG tubes were predominantly inserted during the interval between anesthesia induction and the initiation of surgery in all specialties. Regarding NG tube removal, most specialties followed the general trend, with removal most commonly occurring on POD 1. However, in colorectal cancer surgeries, NG tubes were more frequently removed earlier, specifically on the day of surgery, immediately following the procedure, compared to other specialties (

Fig. 3B).

Most surgeons reported initiating SOW on POD 1, progressing to either a liquid or soft diet on POD 2 (

Fig. 4A). The gastric cancer cohort showed a tendency to delay solid food initiation by one day compared to other cancer surgeries (

Fig. 4B). Across all specialties, surgeons preferred transitioning to solid food by first introducing liquid diets (

Fig. 4C).

Among all respondents, 49% reported routinely prescribing postoperative PN to all patients. The “all-in-one” formula was the most frequently prescribed type, typically administered at 1,000–1,500 kcal/d for three days (

Fig. 5A). This practice was consistent across most specialties; however, the majority of bariatric/metabolic surgery specialists indicated that they generally do not prescribe PN post-surgery. When PN was routinely prescribed across all specialties, including bariatric/metabolic surgery, the ‘all-in-one’ formula at 1,000–1,500 kcal/d was standard, with most respondents opting for a three-day administration period. For bariatric/metabolic surgery, however, a two-day prescription was most common (

Fig. 5B).

However, 33% of respondents selectively prescribed PN for certain patients postoperatively. The primary reasons cited included requirements for extended fasting due to complications, poor oral intake after surgery, or suboptimal nutritional status before surgery. Among those prescribing PN selectively, the ‘all-in-one’ formula at 1,000–1,500 kcal/d for three days remained the preferred choice (

Fig. 5C). Across all specialties, the most common indication for selective PN was the need for fasting following complications: for bariatric/metabolic surgeries, it was primarily used for patients unable to postoperatively tolerate oral intake (

Fig. 5D).

Among all respondents, 21% reported routinely prescribing ONS postoperatively to all patients. The most commonly prescribed supplement was a standard formula, typically given at 400 mL per day, primarily during the hospital stay (

Fig. 6A). For departments routinely prescribing ONS, standard formulas were most commonly used at 400–600 mL per day following gastric and colorectal surgeries. In contrast, high-protein formulas at 400–600 mL per day were preferred for hepatobiliary cancer and metabolic/bariatric surgeries. For gastric cancer surgeries, many respondents indicated that oral nutrition continued post-discharge, while in colorectal and hepatobiliary surgeries, most reported restricting oral nutrition to the hospital stay (

Fig. 6B).

However, a meaningful 47% of respondents selectively prescribed ONS postoperatively for certain patients, primarily due to poor oral intake post-surgery or preoperative nutritional deficiencies (

Fig. 6C). Among those selectively prescribing ONS, the most common practice was to administer a standard formula at 600 mL per day, generally only during the hospital stay (

Fig. 6C, D).

Discussion

Key results

Most surgeons enforce midnight fasting before surgery, with limited preoperative carbohydrate drinks. About 30% use NG tubes preoperatively, often placed after anesthesia induction and removed by POD1. Postoperatively, diets typically start as SOW on POD1, advancing by POD2. Nearly half prescribe routine PN at 1,000–1,500 kcal/d for three days, while some selectively prescribe PN for complications. ONS is routinely given by 21% (usually standard formula), and 47% selectively provide ONS to address poor postoperative oral intake or preoperative nutritional deficits.

Interpretation/comparison with previous studies

Preoperative fasting protocols

ERAS protocols have been progressively implemented worldwide across diverse surgical fields [

13,

14], including abdominal, neurosurgery [

15], orthopedics [

16], and trauma surgery [

17]. International data reflect diverse levels of ERAS adoption across specialties and regions, with significant strides in Europe and North America to incorporate early nutritional support and reduced fasting during perioperative care. Notably, fields like orthopedic and neurosurgery demonstrate comprehensive integration of ERAS protocols to expedite recovery [

16,

17]. Comparatively, Korean surgical practices, particularly in major abdominal surgeries, show partial yet cautious adoption of ERAS guidelines [

8-

10]. The findings of this survey reveal variability in practice patterns across Korean general surgeons, suggesting potential challenges in fully implementing ERAS in abdominal surgery specialties including gastric, colorectal, and hepatobiliary surgery.

Preoperative provision of carbohydrate-rich drinks

As shown in

Fig. 2, one of the main barriers identified is that Korean surgeons often restrict preoperative carbohydrate-rich drink administration, largely influenced by anesthesiology protocols. This practice contrasts with existing research that increasingly recognizes preoperative carbohydrate loading as beneficial for reducing postoperative insulin resistance and promoting recovery [

18]. Although anesthesiology guidelines increasingly recommend preoperative carbohydrate loading [

19,

20], some studies suggest that it may not provide substantial clinical benefits [

21,

22]. This debate may partly explain the challenges in routinely implementing preoperative carbohydrate loading in Korea, where the emphasis on preoperative fasting is already deeply rooted in anesthesiology practices. This underscores the importance of active cooperation from anesthesia teams in modifying fasting protocols within an ERAS framework [

11].

Postoperative dietary progression

The survey results indicate that dietary progression varies among abdominal surgery types in Korea, with solid food intake typically delayed by a day in gastric cancer surgeries compared to other surgeries, including hepatobiliary surgery (

Fig. 4B). Although we expected prolonged fasting periods after pancreatic surgeries, involving extensive gastrointestinal anastomoses compared to gastric cancer surgeries, the findings showed that hepatobiliary-pancreatic (HPB) surgeries typically initiated soft diet on POD 2, whereas gastrectomy patients commonly began soft dietary intake on POD 3. We conducted a sub-analysis that considered surgeries like liver resections or distal pancreatectomies, which do not involve the stomach or pylorus resection. These surgeries might bias the overall data for HPB surgeries, as they generally require shorter postoperative fasting periods than pancreatic surgeries involving the stomach. As shown in

Supplement 2, examining dietary progression by surgery type, procedures impacting the stomach, such as Whipple/PPPD/PRPD, as well as gastric cancer surgeries, generally started solid food intake on POD 3, one day later than other surgeries, with the exception of bariatric/metabolic surgeries. Although the difference in postoperative dietary timing has narrowed compared to the past, this suggests that surgeons still take a somewhat conservative approach to postoperative feeding due to concerns about postoperative complications such as anastomosis site leakage.

Postoperative administration of PN

As shown in

Fig. 5A, a considerable 49% of Korean surgeons routinely prescribe postoperative PN to all patients, reflecting a somewhat conservative approach compared to ERAS recommendations, which advocate selective PN use. The general trend among Korean surgeons follows preoperative “MNNPO” fasting, initiating SOW on POD 1 and advancing to a soft diet by POD 2 (

Fig. 4A). Routine PN administration commonly extends to POD 3 (

Fig. 5C), which is primarily due to the perception that immediate postoperative oral intake alone may not meet nutritional needs. Although it is cost-effective to discontinue PN as soon as patients can tolerate an oral diet, many surgeons favor a bridging period until a stable oral diet is achieved. However, current international guidelines recommend perioperative PN only if enteral intake remains inadequate or contraindicated [

23], primarily due to the risk of infection and increased hospitalization associated with routine PN use [

24]. Studies have shown that ERAS pathways, favoring early oral intake, can reduce dependency on PN and enhance recovery outcomes [

25,

26]. Therefore, establishing guidelines tailored to the Korean medical context would be beneficial, balancing the necessity for supplemental nutrition with the risks associated with prolonged PN use. These guidelines could help streamline postoperative nutritional support, encouraging selective PN use while optimizing patient outcomes and cost efficiency.

Postoperative provision of ONS

The postoperative use of ONS is selective in Korean practice, with 47% of surgeons prescribing them to a subset of patients. This selective approach aligns partially with ERAS guidelines, which recommend ONS primarily for patients with demonstrated malnutrition or insufficient intake. However, the relatively limited use of routine ONS in Korea might reflect a conservative practice culture that reserves nutritional interventions for cases of severe deficiency. International ERAS guidelines advocate broader ONS administration to expedite recovery in patients who can tolerate oral intake [

27-

29]. Korean practice could benefit from a more proactive approach to ONS, especially in high-risk patients, to better align with ERAS goals of minimizing recovery time and reducing postoperative complications.

While efforts were made to include as many general surgeons as possible, it did not encompass all general surgeons in Korea. Consequently, the survey findings may not fully represent perioperative nutritional management practices across all surgical specialties and institutions in Korea. Additionally, the self-reported nature of the survey responses may introduce recall bias or inaccuracies in reflecting actual clinical practices. Finally, although the total number of responses was sufficient, variations in response rates by specialty and surgical procedure could have resulted in biased findings for some surgical protocols.

Conclusion

While there is a strong desire among Korean surgeons to implement ERAS protocols, longstanding practices and cultural habits associated with preoperative fasting and postoperative dietary progression present significant challenges to immediate adoption. This illustrates the difficulty of moving away from established practices and underscores the necessity of a gradual, structured transition toward evidence-based nutritional management aligned with ERAS guidelines. While this survey may not fully represent perioperative nutritional management practices across Korea, it offers valuable insights into current trends and practices. These findings may serve as a useful reference for understanding perioperative nutritional care in Korea and aid in developing nutrition guidelines tailored to the unique contexts of Korean surgical practices.

Supplementary materials

Supplement 1. Survey questionnaire conducted via Google Forms.

Supplement 2. Figure of postoperative dietary progression by surgery.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the past and current members of the External Relation Committee of the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: SWR, MRJ. Project administration: SWR, DSH. Data curation: SHK, HK, GL, JSM, HKO, JHB, YC. Methodology: JHP, MRJ. Formal analysis: JHP, DSH. Supervision: SWR, DSH. Writing – original draft: JHP. Writing – review & editing: all authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by the grant of the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition (2023).

Data availability

Contact the corresponding author for data availability.

Fig. 1Preoperative fasting protocols (A) overall and (B) by specialty. MNNPO = midnight Nil Per Os.

Fig. 2Provision of preoperative carbohydrate-rich drinks: (A) overall and (B) by specialty.

Fig. 3Preoperative use of nasogastric (NG) tubes: (A) overall and (B) by specialty. OP = operation; POD, postoperative day.

Fig. 4Postoperative dietary progression: (A) overall, (B) by specialty, and (C) formulation of the first solid meal provided after surgery. OP = operation; POD = postoperative day.

Fig. 5Postoperative administration of parenteral nutrition (PN). (A) Prescription of PN to all patients after surgery (overall). (B) Prescription of PN to all patients after surgery (by specialty). (C) Prescription of PN to select patients after surgery (overall). (D) Prescription of PN to select patients after surgery (by specialty).

Fig. 6Postoperative provision of oral nutritional supplements (ONS). (A) Provision of ONS to all patients after surgery (overall). (B) Provision of ONS to all patients after surgery (by specialty). (C) Provision of ONS to select patients after surgery (overall). (D) Provision of ONS to select patients after surgery (by specialty).

Table 1Participant demographics and survey response rates

|

Survey period: 2023.2.16–2023.9.2 |

|

Participants |

|

389 |

|

Responses |

551 |

|

Specialty |

Participants |

Responses |

Surgery |

Participants |

Responses |

|

Gastric cancer surgery |

149 (36) |

204 |

DG/PPG |

|

105 (27) |

|

141 |

|

TG/PG |

|

36 (9) |

|

63 |

|

Colorectal cancer surgery |

123 (30) |

142 |

Colectomy |

|

82 (21) |

|

97 |

|

LAR/LATA (±ileostomy) |

|

40 (10) |

|

45 |

|

Hepatobiliary cancer surgery |

109 (27) |

164 |

Hepatectomy

(±hepaticojejunostomy) |

|

39 (10) |

|

61 |

|

Distal pancreatectomy |

|

11 (3) |

|

22 |

Pancreaticoduodenectomy

(Whipple/PPPD/PRPD) |

|

53 (14) |

|

81 |

|

Metabolic and bariatric surgery |

29 (7) |

41 |

Sleeve gastrectomy |

|

17 (4) |

|

31 |

|

Gastric bypass |

|

6 (2) |

|

10 |

References

- 1. MENDELSON CL. The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1946;52:191-205. ArticlePubMed

- 2. Lai L, Zeng L, Yang Z, Zheng Y, Zhu Q. Current practice of postoperative fasting: results from a multicentre survey in China. BMJ Open 2022;12:e060716. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Knight SR, Qureshi AU, Drake TM, Lapitan MCM, Maimbo M, Yenli E, et al. 2022;The impact of preoperative oral nutrition supplementation on outcomes in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery for cancer in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 12:12456. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 4. Canzan F, Caliaro A, Cavada ML, Mezzalira E, Paiella S, Ambrosi E. 2022;The effect of early oral postoperative feeding on the recovery of intestinal motility after gastrointestinal surgery: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 17:e0273085. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Rollins KE, Lobo DN, Joshi GP. 2021;Enhanced recovery after surgery: current status and future progress. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 35:479-89. ArticlePubMed

- 6. van Noort HHJ, Eskes AM, Vermeulen H, Besselink MG, Moeling M, Ubbink DT, et al. Fasting habits over a 10-year period: an observational study on adherence to preoperative fasting and postoperative restoration of oral intake in 2 Dutch hospitals. Surgery 2021;170:532-40. ArticlePubMed

- 7. Zhu Q, Li Y, Deng Y, Chen J, Zhao S, Bao K, et al. Preoperative fasting guidelines: where are we now? Findings from current practices in a tertiary hospital. J Perianesth Nurs 2021;36:388-92. ArticlePubMed

- 8. Jeong O, Kim HG. Implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program in perioperative management of gastric cancer surgery: a nationwide survey in Korea. J Gastric Cancer 2019;19:72-82. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 9. Choi BY, Bae JH, Lee CS, Han SR, Lee YS, Lee IK. Implementation and improvement of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocols for colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg Treat Res 2022;102:223-33. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 10. Shin SH, Kang WH, Han IW, You Y, Lee H, Kim H, et al. National survey of Korean hepatobiliary-pancreatic surgeons on attitudes about the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2020;24:477-83. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Yoon SH, Lee HJ. Challenging issues of implementing enhanced recovery after surgery programs in South Korea. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2024;19:24-34. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Kim EY, Lee IK. Survey and analysis of the application and implementations of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program for surgical patients in the major hospitals in Korea. Surg Metab Nutr 2019;10:32-45. Article

- 13. Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: a review. JAMA Surg 2017;152:292-8. ArticlePubMed

- 14. Smith TW Jr, Wang X, Singer MA, Godellas CV, Vaince FT. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a clinical review of implementation across multiple surgical subspecialties. Am J Surg 2020;219:530-4. ArticlePubMed

- 15. Belouaer A, Cossu G, Papadakis GE, Gaudet JG, Perez MH, Chanez V, et al. Implementation of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) program in neurosurgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2023;165:3137-45. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 16. Choi YS, Kim TW, Chang MJ, Kang SB, Chang CB. Enhanced recovery after surgery for major orthopedic surgery: a narrative review. Knee Surg Relat Res 2022;34:8.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 17. Jain V, Irrinki S, Khare S, Kurdia KC, Nagaraj SS, Sakaray YR, et al. Implementation of modified enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) following surgery for abdominal trauma; Assessment of feasibility and outcomes: a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Am J Surg 2024;238:115975. ArticlePubMed

- 18. Tong E, Chen Y, Ren Y, Zhou Y, Di C, Zhou Y, et al. 2022;Effects of preoperative carbohydrate loading on recovery after elective surgery: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Nutr 9:951676. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 19. Morrison CE, Ritchie-McLean S, Jha A, Mythen M. 2020;Two hours too long: time to review fasting guidelines for clear fluids. Br J Anaesth 124:363-6. ArticlePubMed

- 20. Marsman M, Kappen TH, Vernooij LM, van der Hout EC, van Waes JA, van Klei WA. Association of a liberal fasting policy of clear fluids before surgery with fasting duration and patient well-being and safety. JAMA Surg 2023;158:254-63. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Amer MA, Smith MD, Herbison GP, Plank LD, McCall JL. Network meta-analysis of the effect of preoperative carbohydrate loading on recovery after elective surgery. Br J Surg 2017;104:187-97. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 22. Lu J, Khamar J, McKechnie T, Lee Y, Amin N, Hong D, et al. Preoperative carbohydrate loading before colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Colorectal Dis 2022;37:2431-50. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 23. Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, Higashiguchi T, Hübner M, Klek S, et al. ESPEN practical guideline: clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin Nutr 2021;40:4745-61. ArticlePubMed

- 24. Senkal M, Bonavina L, Reith B, Caruso R, Matern U, Duran M. Perioperative peripheral parenteral nutrition to support major gastrointestinal surgery: expert opinion on treating the right patients at the right time. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2021;43:16-24. ArticlePubMed

- 25. Jochum SB, Ritz EM, Bhama AR, Hayden DM, Saclarides TJ, Favuzza J. Early feeding in colorectal surgery patients: safe and cost effective. Int J Colorectal Dis 2020;35:465-9. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Pu H, Heighes PT, Simpson F, Wang Y, Liang Z, Wischmeyer P, et al. Early oral protein-containing diets following elective lower gastrointestinal tract surgery in adults: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Perioper Med (Lond) 2021;10:10.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 27. Wobith M, Weimann A. Oral nutritional supplements and enteral nutrition in patients with gastrointestinal surgery. Nutrients 2021;13:2655.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 28. Smedley F, Bowling T, James M, Stokes E, Goodger C, O'Connor O, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effects of preoperative and postoperative oral nutritional supplements on clinical course and cost of care. Br J Surg 2004;91:983-90. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 29. Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, Nygren J, Demartines N, Francis N, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations: 2018. World J Surg 2019;43:659-95. ArticlePubMed

, Mi Ran Jung2

, Mi Ran Jung2 , Sang Hyun Kim3

, Sang Hyun Kim3 , Hongbeom Kim4

, Hongbeom Kim4 , Gyeongsil Lee5

, Gyeongsil Lee5 , Jae-Seok Min6

, Jae-Seok Min6 , Heung-Kwon Oh7

, Heung-Kwon Oh7 , Jung Hoon Bae8

, Jung Hoon Bae8 , Yoona Chung9

, Yoona Chung9 , Dong-Seok Han10

, Dong-Seok Han10 , Seung Wan Ryu11

, Seung Wan Ryu11 , The External Relation Committee of the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition

, The External Relation Committee of the Korean Society of Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

Cite

Cite