Indexed in:

Scopus, KCI, KoreaMed

Scopus, KCI, KoreaMed

Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Clin Nutr > Volume 8(1); 2016 > Article

- Original Article Pilot Study for Safety and Efficacy of Newly Developed Oral Carbohydrate-Rich Solution Administration in Adult Surgery Patients

- Won-Bae Chang, Kyuwhan Jung, Sang-Hoon Ahn, Heung-Gwon Oh, Mi-Ok Yoon

- 성인 수술환자에서 새롭게 개발된 경구용 고탄수화물음료의 수술 전 복용으로 인한 효과 및 안전성에 대한 예비연구

- 장원배, 정규환, 안상훈, 오흥권, 윤미옥

-

Journal of the Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2016;8(1):24-28.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15747/jcn.2016.8.1.24

Published online: April 30, 2016

Department of Surgery, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seongnam, Korea

- Correspondence to Kyuwhan Jung Department of Surgery, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 82 Gumi-ro 173beon-gil, Bundang-gu, Seongnam 13620, Korea Tel: +82-31-787-7099, Fax: +82-31-787-4078, E-mail: chungq@snubh.org

• Received: December 24, 2015 • Revised: January 23, 2016 • Accepted: February 12, 2016

Copyright: © Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,557 Views

- 1 Download

- 3 Crossref

Abstract

-

Purpose: In surgical procedures under general anesthesia, 6 to 8 hours of a nulla per os (NPO; nothing by mouth) has been regarded as essential for prevention of respiratory complication such as aspiration. However, recent studies have reported that oral intake of water and other clear fluids up to 2 hours before induction of anesthesia does not increase respiratory problems. The purpose of this pilot study is to investigate the safety and efficacy of a newly developed carbohydrate-rich solution in elective hernia repair surgery patients.

-

Methods: A group of 30 adult patients scheduled for elective surgeries under general anesthesia were enrolled. The enrolled study group of patients was permitted to drink a carbohydrate-rich solution until two hours before the operation without volume limitation. Respiratory complication was investigated in the patients using the carbohydrate-rich solution until two hours before induction of general anesthesia. The feelings of thirst, hunger sense were measured pre- and post-operatively. In addition, hoarseness of voice, nausea and vomiting were investigated post-operatively. Satisfaction regarding the short time of fasting was measured. Visual analogue scale (VAS) was used for measurement of these six variables.

-

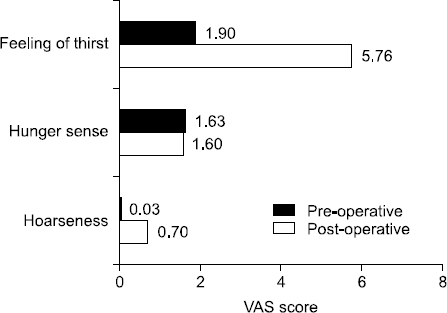

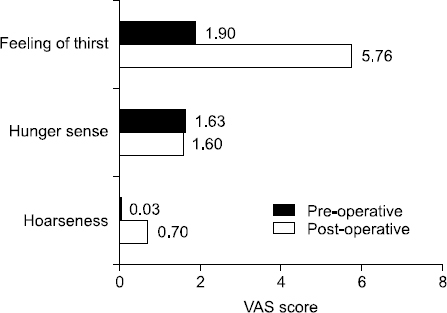

Results: No patients showed serious respiratory complication such as dyspnea, desaturation. Eight of 30 study group patients complained of mild hoarseness. Most symptoms of hoarseness were mild, with VAS score less than 3 out of 10. Two patients complained 5 out of 10. Six patients felt nausea and 1 patient had vomiting. Pre/post-operative hunger sense and thirst feeling were 1.63/1.60 and 1.90/5.76, respectively. The satisfaction score was 3.00 out of 4.

-

Conclusion: Allowing the administration of an oral carbohydrate-rich solution in elective surgery patients requiring general anesthesia is safe without serious respiratory complications and effective in providing satisfaction.

INTRODUCTION

General anesthesia can cause several problems to the surgical patient peri-operatively. A pulmonary aspiration and aspiration induced pneumonitis due to the gastric contents regurgitation is one of most serious complication. So far, six to eight hours of pre-operative nulla per os (NPO; nothing by mouth) on the purpose of gastric emptying has been regarded as the best method to reduce respiratory aspiration of gastric contents1 because the volume and acidity of the gastric content are main risk factors of the pulmonary aspiration.2

However, against to this strong belief, several studies have shown that oral intake of water and other clear liquids up to 2 hours before induction of anesthesia does not increase the gastric residual contents and acidity. One of studies reported that pre-operative water intake resulted in a significant decrease of gastric contents than patients who followed standard midnight fasting regimen after surgery.3

Another problem of preoperative long time fasting is to cause serious inconvenience to patients and this could induce post-operative negative psychological effects.4 Recent studies show that nausea and vomiting reduced in patients who took fluid until 2 hours before general anesthesia. Therefore, minimizing the fasting time will be able to attenuate perioperative discomfort5-7 and post-operative negative physiologic change.

As the interest of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) increases, many studies are reporting the safety and efficacy of preoperative loading of carbohydrate-rich solution.8 The preoperative fasting guideline mentions that the duration of preoperative fasting needs be 2 hours for liquids and 6 hours for solids.3

The aim of this pilot study was to investigate the safety and efficacy in terms of satisfaction of the newly developed carbohydrate-rich solution to patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board (B-1307/212-004) at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, South Korea. All patients were informed and they agreed to the purpose and procedures of this study at the last visit in outpatient clinic before operation.

Thirty of adult patients older than eighteen years old who scheduled for an elective surgery under a general anesthesia were enrolled. Patients with underlying respiratory disease or ASA (American Society of Anestheologists) class III, IV were excluded from this study. The types of surgery were open inguinal hernia repair or endoscopic total extra-peritoneal plasty (TEP). This study was conducted over 3-month period from September 2013 to November 2013 in Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, South Korea.

Carbohydrate-rich solution (12.6 g/100 mL carbohydrates, 50 kcal/100 mL 260 mOsm; NO-NPO; Daesang Wellife, Seoul, Korea) was provided to patients at the last visit of outpatient clinic. After patients were admitted the day before operation, they were allowed to drink a carbohydrate-rich solution from midnight to 2 hours before surgery without limitation of amount.9

The feeling of thirst, hunger sense were measured right before the patients were going to operating room and in the recovery room by using the visual analogue scale (VAS) which had scales from 0 to 10. All surgical procedures were performed under general anesthesia and nasogastric tube was inserted after intubation. Gastric residual content was aspirated through the nasogastric tube, then the volume and acidity were measured after surgical procedure just after intubation.

In the recovery room after surgery, six different variables were evaluated: feeling of thirst, hunger sense, hoarseness of voice, satisfaction, nausea and vomiting7,10 by using the VAS to evaluate their subjective senses. Also patients were observed weather they had any acute respiratory symptoms such as vigorous cough or dyspnea, desaturation.

RESULTS

The ingredient of oral carbohydrate-rich solution which was used in this study is shown (Table 1). The gender, median age, volume of carbohydrate rich solution and interval between the last carbohydrate solution administration and induction of anesthesia are shown (Table 2). Twenty nine of 30 patients were male. The median age of patients was 58.63. The median volume patients drank before operation was 307.0 mL (30∼800 mL). The median time period between intake of carbohydrate-rich solution and the induction of anesthesia was 264.9 minutes (70∼490 minutes). Aspiration through nasogastric tube was tried to measure the volume and acidity. But no residual gastric fluid volume over 1 mL was aspirated, so pH could not been measured. Eight of 30 patients complained mild hoarseness. Most of symptom of hoarseness was mild, which VAS score were less than 3 out of 10 except 2 patients who complained moderate degree in 5 out of 10. Six out of 30 patients (20%) complained nausea and one patient (3.3%) had vomiting. Pre-operative hunger sense was 1.63 and it was 1.60 out of 10 post-operatively. It did not show significant difference. The pre and post-operative feeling of thirst were increased from 1.90 to 5.76 out of 10 (Fig. 1). The score of satisfaction was 3.00 out of 4. None of patients had acute serious pulmonary complication such as desaturation or dyspnea.

Table 1

The content of oral carbohydrate-rich solution

Table 2

Patients’ characteristics

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 58.6 (27~79) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 29 (96.7) |

| Female | 1 (3.3) |

| Carbohydrate rich solution volume (mL) | 307.0 (30~800) |

| Interval of last drink to induction (min) | 264.9 (70~490) |

DISCUSSION

Pulmonary aspiration and aspiration induced pneumonitis is one of the serious complication in a surgery under general anesthesia and pre-operative fasting has been regarded as the safest method to prevent the risk of aspiration of stomach contents during anesthesia. Six to eight hours of fasting is generally accepted to achieve the prevention of aspiration.

However, recent studies have reported that the long duration of fasting before surgery cause a significant inconvenience to patients and intake of water or other clear fluid up to 2 hours before induction of anesthesia does not increase aspirated pulmonary complication which was induced by regurgitation of gastric contents.3,5,8

T1/2 of normal gastric emptying of solid food is more than 2 hours. In contrast, it is less than 1 hour in clear liquid food.11,12 Under this physiologic difference of gastric emptying time between solid and liquid, many groups have studied and shown that the oral intake of water and other clear liquids up to 2 hours before induction of anesthesia does not increase the gastric residual contents to cause aspiration. Brady et al.3 showed no difference in intra-operative gastric volume between unlimited volume of clear fluid and fasted groups. In this study, no residual gastric fluid volume over 1 mL was aspirated through nasogastric tube in all 30 patients who took the newly developed carbohydrate-rich solution up to 2 hours before surgery.

Eight of 30 patients had mild to moderate degree of hoarseness after operation. This symptom of temporary hoarseness in the studied patients might be from endotracheal intubation or chemical irritation of aspirated gastric contents. But a temporary hoarseness after endotracheal intubation is one of most common complication in general anesthesia. It occurs from 14.4% to 50% of patients who underwent endotracheal intubation.13-15 All of our patients who showed post-operative hoarseness were recovered completely by the next day of operation. This may be the evidence the post-operative temporary hoarseness is more likely from the endotracheal intubation instead gastric contents aspiration.

Six patients (23.3%) complained nauseous feeling and one patient had vomiting one time at the recovery room. In general, the incidence of post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) after general anesthesia is up to 30% when inhalational anesthetics are used.16 Also recent studies have reported that the incidence of PONV were lower in the group of using carbohydrate-rich solution than in the fasted group between 12 hours and 24 hours after surgery.4 Therefore, PONV of patients are considered as the result of residual anesthetic gas or narcotics effect than increased gastric residual contents.

Pre- and post-operative scores of hunger sense were 1.63 and 1.60. In contrast, the feeling of thirst was increased from 1.90 pre-operatively to 5.76 post-operatively. The thirsty feeling is a very common discomfort in immediate post-operative patients after general anesthesia. According to Aroni et al.,17 75% of patient who kept more than 6 to 8 hours of fasting before general anesthesia felt thirst in the recovery room. Therefore, the thirsty feeling can be regarded as a common symptom after general anesthesia regardless fasting time. The focused result was their low hunger sense score by using oral carbohydrate-rich solution and this low hunger sense seems to be directly associated to high satisfaction score of patients post-operatively (3.0 out of 4).

All of patient who participated in this study did not have any acute respiratory complication such as desaturation, dyspnea or productive cough and discharged at the next day of surgery.

This study is not conclusive because it has several limitations. First, it is a single arm study without control group (6 to 8 hours long fasting) which can be compared with. Also, the number of enrolled patients is too small to make a confirmative conclusion. Based on the result of this study, we will have initiative to continue a well designed randomized control study with enough number of patients.

- 1. McIntyre JW. Evolution of 20th century attitudes to prophylaxis of pulmonary aspiration during anaesthesia. Can J Anaesth 1998;45(10):1024-30. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 2. Søreide E, Eriksson LI, Hirlekar G, Eriksson H, Henneberg SW, Sandin R, et al. Task Force on Sc andinavian Pre-operative Fasting Guidelines Clinical Practice Committee Sc andinavian Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine. Pre- operative fasting guidelines:an update. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2005;49(8):1041-7. ArticlePubMed

- 3. Brady M, Kinn S, Stuart P. Preoperative fasting for adults to prevent perioperative complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(4):CD004423.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Yilmaz N, Cekmen N, Bilgin F, Erten E, Ozhan MÖ, Coşar A. Preoperative carbohydrate nutrition reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting compared to preoperative fasting. J Res Med Sci 2013;18(10):827-32. PubMedPMC

- 5. Hausel J, Nygren J, Lagerkranser M, Hellström PM, Hammarqvist F, Almström C, et al. A carbohydrate-rich drink reduces preoperative discomfort in elective surgery patients. Anesth Analg 2001;93(5):1344-50. ArticlePubMed

- 6. Yurtcu M, Gunel E, Sahin TK, Sivrikaya A. Effects of fasting and preoperative feeding in children. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15(39):4919-22. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Schreiner MS, Triebwasser A, Keon TP. Ingestion of liquids compared with preoperative fasting in pediatric outpatients. Anesthesiology 1990;72(4):593-7. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 8. Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Von Meyenfeldt M, Revhaug A, Dejong CH, Lassen K, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery:a consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr 2005;24(3):466-77. ArticlePubMed

- 9. Campbell A. Pre-operative fasting guidelines for children having day surgery. Nurs Child Young People 2011;23(4):14-9. Article

- 10. Bopp C, Hofer S, Klein A, Weigand MA, Martin E, Gust R. A liberal preoperative fasting regimen improves patient comfort and satisfaction with anesthesia care in day-stay minor surgery. Minerva Anestesiol 2011;77(7):680-6. PubMed

- 11. Hellmig S, Von Schöning F, Gadow C, Katsoulis S, Hedderich J, Fölsch UR, et al. Gastric emptying time of fluids and solids in healthy subjects determined by 13C breath tests:influence of age, sex and body mass index. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;21(12):1832-8. ArticlePubMed

- 12. Vasavid P, Chaiwatanarat T, Pusuwan P, Sritara C, Roysri K, Namwongprom S, et al. Normal solid gastric emptying values measured by scintigraphy using Asian-style meal:a multicenter study in healthy volunteers. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;20(3):371-8. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Jones MW, Catling S, Evans E, Green DH, Green JR. Hoarseness after tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia 1992;47(3):213-6. ArticlePubMed

- 14. Mencke T, Echternach M, Kleinschmidt S, Lux P, Barth V, Plinkert PK, et al. Laryngeal morbidity and quality of tracheal intubation:a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2003;98(5):1049-56. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 15. Martins RHG, Braz JRC, Dias NH, Castilho EC, Braz LG, Navarro LHC. Hoarseness after tracheal intubation. Rev Bras Anestesiol 2006;56(2):189-99. PubMed

- 16. Rüsch D, Eberhart LH, Wallenborn J, Kranke P. Nausea and vomiting after surgery under general anesthesia:an evidence- based review concerning risk assessment, prevention, and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010;107(42):733-41. PubMedPMC

- 17. Aroni P, do Nascimento LA, Fonseca LF. Assessment strategies for the management of thirst in the post-anesthetic recovery room. Acta Paul Enferm 2012;25(4):530-6. Article

References

Figure & Data

REFERENCES

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- The safety and effect of preoperative reduced fasting time by oral clear liquid administration in adult surgery patients: a randomized controlled trial

Donghyoun Lee, Soo-Jin Kim, Won-Bae Chang

Annals of Surgical Treatment and Research.2025; 109(1): 1. CrossRef - Oral high-carbohydrate solution as an alternative dietary modality in patients with acute pancreatitis

See Young Lee, Jaein Lee, Jae Hee Cho, Dong Ki Lee, Yeseul Seong, Sung Ill Jang

Pancreatology.2024; 24(7): 1003. CrossRef - Patient-reported outcome measures on intake of nutrition drink for nutritional supplements after periodontal surgery

Hyeong-Seok Kim, In-Woo Cho, Hyun-Seung Shin, Jung-Chul Park

Journal of Dental Rehabilitation and Applied Science.2016; 32(3): 176. CrossRef

Pilot Study for Safety and Efficacy of Newly Developed Oral Carbohydrate-Rich Solution Administration in Adult Surgery Patients

Fig. 1

Visual analogue scale (VAS) score of patients’ symptoms.

Fig. 1

Pilot Study for Safety and Efficacy of Newly Developed Oral Carbohydrate-Rich Solution Administration in Adult Surgery Patients

The content of oral carbohydrate-rich solution

| Contents per 100 mL | Standard nutrition contents (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Calorie (kcal) | 50 | |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 12.6 | 4 |

| Fiber | 0 | 0 |

| Sugar | 2.1 | |

| Protein (g) | 0 | 0 |

| Fat (g) | 0 | 0 |

| Saturated | 0 | 0 |

| Trans | 0 | |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 0 | 0 |

| Na (mg) | 50 | 3 |

| Ca (mg) | 3 | 0 |

| P (mg) | 1 | 0 |

| K (mg) | 61 | 2 |

| Mg (mg) | 1 | 0 |

| Cl (mg) | 4 | |

| Osmotic pressure (mOsm) | 260 | |

| Renal solute load (mOsm) | 28 | |

| Brix (degree) | 14 | |

| pH | 4.6 |

Patients’ characteristics

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 58.6 (27~79) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 29 (96.7) |

| Female | 1 (3.3) |

| Carbohydrate rich solution volume (mL) | 307.0 (30~800) |

| Interval of last drink to induction (min) | 264.9 (70~490) |

Values are presented as median (range) or number (%).

Table 1 The content of oral carbohydrate-rich solution

Table 2 Patients’ characteristics

Values are presented as median (range) or number (%).

E-submission

E-submission KSPEN

KSPEN KSSMN

KSSMN ASSMN

ASSMN JSSMN

JSSMN

Cite

Cite